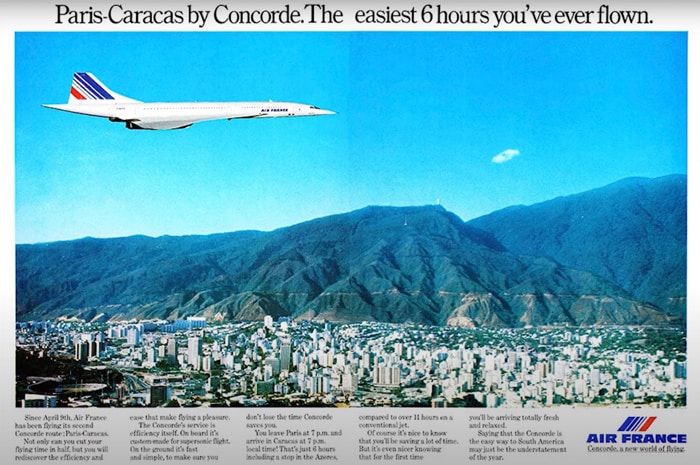

When 20% of its population fled the country, Venezuela's economic crisis turned into a regional affair for the entire Americas. Of those who stayed behind, all too many were imprisoned, tortured or killed by the authoritarian government. Venezuela turned from paradise to hell.

Would you invest in such a basket case country? And even if you wanted to, how would you go about it?

Once again, Undervalued-Shares.com goes where others don't dare to tread.

This exclusive, in-depth investigation will introduce you to one specific investment opportunity that could increase in value by 2-55 times (with a minimum of 5 times being fairly realistic). It is 100% geared towards Venezuela but trades on the Canadian stock exchange, which should make it accessible to anyone with a normal brokerage account (except US Americans which are prohibited from accessing most Venezuelan assets). I'll also point you towards a variety of other options.

Venezuela is a case of crisis investing unlike any other.

Let's delve right in!

A once fashionable story that has gone out of fashion

Until a few years ago, Venezuela was one of those investment cases that everyone in the hedge fund world (and beyond) had already received countless pitches for. The story was simply too obvious. A basket case country, lots of oil, outstanding distressed securities in the triple-digit billions, and a multi-bagger investment performance if or when it all turned around.

Until 2018, you could even get serious institutional research about investing in distressed Venezuelan assets, with firms like Deutsche Bank, Bank of America, and Natixis publishing regular missives.

Back then, Undervalued-Shares.com couldn't have contributed anything that hadn't already been printed elsewhere multiple times over and with a much greater level of detail.

Then came Donald J. Trump's sanctions package of late 2017.

Building on the previous sanctions put in place by George W. Bush and expanded by Barack Obama, the Trump administration banned US persons from participating in certain Venezuelan debt issues and even from purchasing on secondary markets. The finer details of these sanctions are complex but in effect, Washington made it largely impossible for US investors to deal in Venezuelan securities (or any other assets that risk-averse brokerage firms viewed as equivalent to Venezuelan assets).

Up until that point, the New York hedge fund scene had been among the most active participants in distressed Venezuelan assets. The renewed sanctions made this market largely dry up.

If you have been following this subject for some time (as I have), you will have noticed that following the Trump sanctions package, overall reporting about investing in Venezuela had decreased dramatically.

When hardly anyone even pays attention anymore, I get interested – because that's when you can find the most interesting market inefficiencies to exploit to your own benefit.

What's more, Venezuela simply makes for a fascinating economic case study.

From caviar to trash

Venezuela has recently been a byword for economic crisis, but those over the age of 55 will remember that there once was a time when the opposite held true. During the 1970s, the country was often called "Saudi Venezuela". As one of the founding members of OPEC, it benefitted from the rapidly rising oil price.

Raúl Gallegos' 2016 book "Crude Nation: How Oil Riches Ruined Venezuela" described the period as follows:

"The country became known for having the best French, Italian, Spanish, and Middle Eastern restaurants in Latin America, many of them run by famed chefs. Venezuela became one of the largest importers of premium alcohol, like whiskey and champagne, as well as luxury vehicles, like Cadillac El Dorado. … That same year, the per capita income rivalled that of West Germany."

It wasn't going to last.

During the 1980s, falling oil prices started to push the country into the first phase of its long, gradual decline.

It could have all been avoided, or at least the fall could have been a lot softer. During the 1970s, Venezuela had actually been the first country on Earth to create a sovereign wealth fund to stash away some of the oil income for future generations to enjoy. Had it held course, Venezuela could be where Norway is today. However, the fund received little money, and what it did receive was quickly spent on political pet projects of the country's elite. What happened (or didn't happen) at the sovereign wealth fund pretty much sums up the past decades of Venezuela's political mismanagement.

Frustrated by this situation, the country's population voted Hugo Chávez into office in 1999. Chávez aligned himself with Marxist-Leninist governments of countries like Cuba, and he was seen as a part of the socialist "pink tide" that swept Latin America at the time. His regime temporarily benefitted from record-high oil income in the 2000s when oil reached up to USD 148 per barrel. Chávez became known for both his extensive social programmes and the nationalising of entire industries.

Chávez died from cancer during his fifth term in 2013, but his successor, Nicolás Maduro, continued in the same vein. Venezuela became ever more authoritarian, and its economy was increasingly cut off from key markets, not the least because of increasing international sanctions. Under Maduro, Venezuela suffered its biggest-ever economic decline. Few expected the country to fall even further, but fall it did.

Nicolás Maduro (image credit: StringerAL / Shutterstock.com).

As Stabroek News reported on 22 July 2022: "In 2016, the economic crisis reached its most critical point for Venezuelan households. That year, 70 per cent of Venezuelans lost an average of over 17 pounds of weight. Many ate whatever they could, only once a day. Photos and videos circulated on social media showing some people eating garbage, a situation that existed in several cities across the country."

These images circulated around the world, and they continue to shape the country's reputation to this day. Most have long written off Venezuela as a destination for investment.

Could it ever make a comeback?

The country does still have a few trump cards up its sleeve.

Booming commodity prices are bringing Venezuela back in focus

One of the reasons why Venezuela is worth keeping on the radar are its incredible natural assets.

There are countries that have lots of natural resources, and then there is Venezuela.

No other country on Earth – not even Saudi Arabia – has more oil than Venezuela. Its oil reserves of 300bn barrels represent about 20% of the world's proven reserves.

Possibly more relevant in the current context is the fact that Venezuela also has the world's tenth largest gas reserves, ahead of Algeria (11th) and even Norway (21st).

Throw in vast deposits of gold, iron ore, bauxite, and gems for good measure, as well as the endless pristine beaches along the Caribbean, and natural wonders such as the famous table-top mountains. In theory, Venezuela has everything it takes to make a decent living off tourism alone, like so many other countries in the region.

Venezuela's table-top mountains ("tepui").

Sadly, all of these assets have long been caught up in a complex political situation, and it'd take a brave man to predict that Venezuelan politics were about to take a turn for the better. Still, there have been signs, of late, that the situation is improving.

Most notably, the price of Venezuelan debt instruments has been rallying.

As Bloomberg reported on 18 March 2022, "Venezuelan bonds …. have jumped from very low levels."

The prices for Venezuelan bonds are probably the single most useful indicator of how financial markets view the country's prospects.

In late 2017, the Republic of Venezuela and its state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), had defaulted on bonds worth USD 60bn. In total, Venezuelan entities have outstanding defaulted debt securities to the tune of USD 150bn (no one knows the precise total figure because there is also a lot of private debt owed to banks). Defaulted Venezuelan debt is the largest pool of contested assets on planet Earth today.

PDVSA is Venezuela's equivalent to Gazprom in Russia (image credit: testing / Shutterstock.com).

Given the sheer amount of outstanding debt, the idea of buying distressed bonds had always been the most obvious idea for anyone who wanted to claim a stake in Venezuela's potential turnaround. Why is defaulted debt of such interest? As described in great detail in my 6 February 2020 report about ancient Cuban debt claims, a bankrupt country can only go back to tap international financial markets once it has agreed some kind of solution for its existing external debt. That's why even a rogue country like Venezuela will eventually strike a deal with existing bond holders and pay them at least a small percentage of the monies owed – if, in exchange, it's let off the hook for the remainder.

In the past, buying distressed bonds from countries like Iraq, the Soviet Union or post-war Vietnam has been a way to make many times your money – just take a look at the legendary case of André Kostolany, the late German speculator and book author, who made 100 times his money with pre-revolutionary Czarist debt which he bought on the Paris stock exchange (see my Cuban debt report for more details).

Venezuela's combination of vast natural wealth, huge outstanding defaulted debt, and the first signs of political and economic changes made me take another in-depth look.

Indeed, during the period from 2019-2021, much had changed in Venezuela. Then came the events of 24 February 2022, and the world's renewed interest in fossil fuels sourced from countries that are not caught up in armed conflict. Since the war in Ukraine broke out, the situation of Venezuela has been set within a completely changed world. Put simply, Venezuela has got what others urgently need – oil, gas, and also fertile farmland.

It's no longer surprising to learn that Venezuela reported a 12.3% economic growth during the first half of 2022. This is a staggering figure that is worth a closer look.

A new normal for Venezuela (source: Tasnim News Agency, 26 July 2022).

The first green shots of recovery

First, a spoiler alert.

I am far from predicting a quick, significant turnaround of Venezuela's economy.

As the recent webinar "Venezuela's shifting business landscape: Barriers, challenges & opportunities" (organised by pioneer market broker Auerbach Grayson and Caracas brokerage firm Grupo Solfin) concluded, there are multiple possible scenarios for the country's politics, ranging from a complete change to things remaining stuck. Both Venezuela's political and economic situation are very complex, and all that one can do at this stage is to create a list of possible scenarios.

However, it is beyond any reasonable doubt that the situation has recently stabilised at a low point. In some parts of the economy, a recovery has started to take place:

- Hyperinflation has ended, and the inflation rate is down from formerly 10,000,000% to ≈140% p.a.

- Oil production has increased, from 400,000 to recently 700,000 barrels per day (compared to 3.5m before the country's collapse).

- Consumer loans are up 23%, indicating some of the growth is trickling down.

The question is, how sustainable is the recovery?

The experts at Grupo Solfin have done the work to develop different scenarios, with predictions for 2023 GDP growth ranging from 10.3% at the lower end to 37.6% at the top end.

Also, what has definitely started to change already is the overall tone of the conversation:

- European energy companies Repsol (ISIN ES0173516115, BME:REP) and ENI (ISIN IT0003132476, BIT:ENI), are currently working overtime to increase the import of Venezuelan energy to Europe. The US Department of State allowed both firms to engage in an oil-for-debt deal with PDVSA, the Venezuelan state-owned oil company. The deal helps Europe with its energy problems, and it allows both firms to collect outstanding debts and dividends from their joint ventures with PDVSA. At year-end 2021, ENI had EUR 1.3bn in receivables outstanding, which it now hopes to collect by getting Venezuelan oil deliveries.

Source: Reuters, 6 June 2022.

- Chevron Corporation (ISIN US1667641005, NYSE:CVX) had long kept production facilities in Venezuela, and even runs a refinery in Mississippi that was specifically built to process Venezuelan oil. The company is now looking to "revamp its Venezuela oil pact in a bid to lift output", as Bloomberg reported in detail on 6 July 2022.

- Gramercy Funds Management has started to invest in oil and gas exploration in Venezuela. The New York-based fund manager formed a joint venture with an arm of Inelectra Group, a Caracas-based firm that holds a stake in the Gulf of Paria oil project off Venezuela's eastern coast, where it found oil in 2001. This is particularly noteworthy since Gramercy is famous for successfully exploiting the recurring debt defaults of Argentina, which I reported on in a Weekly Dispatch on 26 March 2021. These are players who know what they are getting themselves into.

- As Bloomberg reported on 23 August 2022: "Venezuela is in talks with the global energy giant Siemens Energy AG to repair power plants … The country plans to spend $1.5b to rebuild system. … The German company was granted licenses by the US Treasury to work with the state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela SA, which owns the plants."

Venezuela is currently considering how to structure potential additional joint ventures that could attract large oil operators back to the country. It all makes a lot of sense. After all, through their past work in the country, global oil companies are familiar with the Venezuelan geology. The location of the oil reserves is clearly defined; most are onshore, and most are close to coastal ports or pipeline networks. Much as there is heightened political risk in Venezuela, the so-called geological risk is at a minimum.

Venezuela's oil reserves are mostly heavy crude, i.e. low-quality oil that needs special processing, comes with much higher costs, and pollutes the environment. In my 30 December 2021 report on Petrobras, the Brazilian state-owned oil company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, I had spelled out why Venezuela's oil industry was unlikely to ever reach its former glory again, even if it had the necessary investment and political stability. Even the conflict in Ukraine is unlikely to change that, because heavy crude is of limited attractiveness economically. Still, the oil reserves could provide Venezuela with a much-needed kickstart which could then be followed by focussing on growing other sectors of the economy.

Some investors with a knack for getting in early have already recognised as much. It's visible in the renewed interest in the Caracas stock exchange, as highlighted by the Financial Times on 11 January 2021:

"In November, the country's leading rum-maker, Santa Teresa, became the first company to issue fixed income dollar-denominated bonds on the local market. That was possible because the state changed its rules last year to allow exporters to do so, which would have been unthinkable under Chávez. Santa Teresa's issue was modest – $300,000 of one-year bonds paying a return of 4 per cent – but it is a first step.

Equities, too, are enjoying something of a recovery, albeit at drastically reduced levels from their heyday in the early 1990s. The number of shares traded in 2019 was over eight times higher than in 2016. The number of investors in the 27 actively traded companies on the Caracas bourse has risen fivefold in five years."

As Grupo Solfin also reported in its webinar: "In recent months, we are beginning to see increased investor interest in our country."

Who are the investors getting in on this while the rest of the world still hesitates?

There is one family that is particularly well-placed to assess these opportunities, and it's in the process of deploying large amounts of pioneering investments in the country. Given its history, the family's commitment could be seen as akin to insider purchases.

This insider family is piling in

Eduardo Cisneros, the scion of a Florida-based billionaire family, has recognised that the biggest bargains are usually struck during a crisis-ridden country's darkest period. His ancestors originally fled Cuba in the 1930s, then made money in Venezuela during its boom times, before relocating to the safety of the US.

The Cisneros are said to have remained on good terms with the regime in Venezuela, as evidenced by the fact that they were allowed to retain important assets in the country while thousands of other family-owned companies were seized. Even now, Venezuelans drink the family's beer, use phones and data from its wireless provider, and watch TV from its station. The Cisneros are no ordinary investors, as far as Venezuela is concerned.

In spring 2021, Eduardo Cisneros made headlines for having raised USD 200m for his Venezuelan investment vehicle, the 3B1 Guacamaya Fund.

As Bloomberg reported on 22 March 2021:

"The fund has already used about $60 million of that cash to snap up Venezuelan businesses, including a paint maker, over the past year, according to several people with knowledge of the deals who asked not to be named because they weren't authorized to speak publicly about the matter.

…

'The opportunities for profit are immensely high in the first phase of economic recovery,' said Peter West, an economic adviser at London's EM Funding.

…

Back in Caracas, a newly-formed local association for private capital named Venecapital held an event earlier this month entitled: 'Venezuela, back on the radar of international investors.' In it, speakers heralded Venezuela as the frontier market with the greatest potential, saying those who seize opportunities in the nation aren't sitting around waiting for the regime change that never seems to come. They pointed to telecom, real estate and the gas and oil service sectors as attractive targets for foreign investors."

Cisneros will probably have been attracted by Venezuela's low 28% utilisation rate of its industrial sector (in comparison, Brazil and even Argentina have a 80% and 75% utilisation rate, respectively). These are the kind of crisis conditions where ultra-contrarian investors can strike bargains similar to those of Russia during the 1990s, and all the more so if they are politically connected.

There are signs aplenty that something potentially quite interesting is starting to take shape in Venezuela. Bloomberg reported about some of it in a 7 June 2022 feature: "Venezuela's Capitalist Playground Has $200,000 Ferraris and a Bustling Casino

Almost every data point shows the economy is improving. The country's gross domestic product is expanding by anywhere from 1.5% to 20%, depending on which economist is forecasting. Hyperinflation officially came to a halt in January. Some of the 6 million Venezuelans who fanned out across Latin America in search of something – anything – better have started to move back home. … Foreign investors who've shunned the country, in part because they fear violating US sanctions, have begun to visit."

Make no mistake, Venezuela continues to suffer economically in more ways than one, and the largest part of its population has not yet benefitted from the first signs of a turnaround as mentioned in the Bloomberg article. As La Prensa Latina pointed out on 19 August 2022, millions of Venezuelans are "still badly in need of humanitarian aid despite economic recovery".

Politically, the situation remains far from clear-cut due to contradicting signals from the Venezuelan government, such as the "temporary" introduction of the dollar as a parallel currency. As the Bloomberg article concluded, "Venezuela's economy is something of a Potemkin village. It may lead to a new path, or everything may fall apart just as fast."

Still, some are eager to invest not despite of this situation, but because of it. The Cisneros family is one such case, and it is putting its decades-long experience and far-reaching political network to use.

How can ordinary investors get in and be part of the Venezuela story?

Provided you don't hold an US-American passport (sanctions!), Undervalued-Shares.com has the answer.

An easy way to buy legal claims against Venezuela

Long-time Undervalued-Shares.com readers will already be familiar with the idea of buying distressed debt. They will also be familiar with the concept of litigation funding, which I described in great detail in a report that I shared with Undervalued-Shares.com Members in March 2022 (and which centred around a multi-billion dollar legal claim against Argentina). In essence, someone with a large legal claim who doesn't have the money to pursue the claim in court can get the costs of the legal case financed by someone else in exchange for a profit share if the case is won.

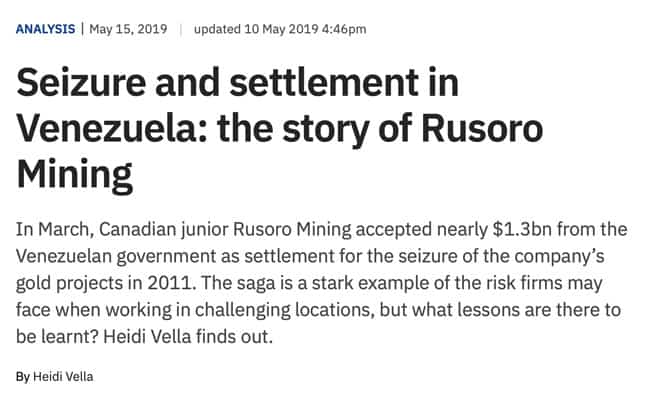

In the case of Venezuela, there is an almost forgotten stock trading in Canada that allows investors to combine the two. Rusoro Mining (ISIN CA7822271028, CA:RML) is a company that used to operate a gold mine in Venezuela, but which nowadays is effectively dormant, except its ongoing lawsuit against the Republic of Venezuela.

Between 2006 and 2008, Rusoro Mining had acquired Venezuelan mining licences that gave it gold reserves of 5.6m ounces, as well as further possible 6.8m ounces subject to additional exploration work. In 2009, the company produced 126,000 ounces from its core gold field, and a further 25,000 ounces from a co-owned project.

In 2011/12, Venezuela nationalised all mining assets without paying suitable compensation. Rusoro Mining didn't just take this laying down, but teamed up with a litigation financier to provide millions of upfront costs for a lawsuit that was going to claim USD 3.3bn in compensation from Venezuela.

The company's primary legal strategy consisted of an international arbitration proceeding launched in the World Bank's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Four years later, the arbiters made an unanimous decision in favour of Rusoro Mining, granting USD 967m in damages plus interest. At the time, the total claim equated over USD 1.2bn. Additional interest has since accumulated, at a rate of over USD 80m p.a., and will keep accumulating. As of today, the claim amounts to USD 1.7bn including interest, though some of that will have to go to the litigation funder, London-based Calunius Capital.

In comparison, the Rusoro Mining's current market cap based on its fully diluted share capital of 585.6m shares is a mere USD 32m (CAN 41m). Even just the additional interest accumulating each year is over twice the current market cap. By distressed debt standards, this is a cheap claim to buy into.

A handy overview of the timeline (source: Mining Technology, 15 May 2019).

This legal saga has since taken a number of additional twists and turns (for details, see the company's website). In short, Venezuela launched its own legal case to have the claim thrown out, but backtracked in October 2018 as part of a settlement agreement. The country agreed to pay Rusoro Mining USD 1.28bn, with USD 100m due immediately and further payments supposed to be made in monthly instalments over five years. A further legal episode launched by Venezuela in French courts also recently ended in victory for the company. Venezuela even once tried to send some of the cash to Rusoro Mining, only for a Canadian bank to refuse accepting the bank transfer out of fears over the sanctions.

So far, Rusoro Mining never got these USD 100m but found itself in a long queue of other international creditors. The company's management will have known this ahead of signing the agreement, but it figured it was going to be easier to negotiate a solution for an uncontested claim than a contested one.

Will Rusoro Mining ever be paid those USD 1.7bn in full? Probably not, simply because Venezuela is too poor to pay. It would be politically inexpedient to pay such a large sum to settle an individual claim brought by one tiny company.

Still, Venezuela will eventually have to settle this case if the country ever wants to get back on the good books of international investors. There are ways and means to achieve a solution that works for both, and both parties have a degree of leverage over the situation. Such a mix is usually a good starting point for an eventual settlement. In August 2021, Venezuela used its ownership of a refinery in the Dominican Republic to settle outstanding debt with another group of foreign investors, and effectively paid 24% of the outstanding debt.

Experts for such situations point out that Venezuela has other foreign assets worth about USD 6bn. On 1 February 2022, Reuters reported that Maduro's government was "maintaining contact with holders of the country's bonds and is willing to make good on payment obligations which have gone unattended since the end of 2017." None of this is a surprise and comes from the standard playbook applied in similar situations.

The stock of Rusoro Mining seems to be an investment that could multiply in value if or when a decent settlement gets not just agreed but actually executed. A bit of lateral thinking may be required to get things to the finishing line. Rusoro Mining could reclaim its mining operation in Venezuela and get repaid through a deal that involves a temporary lowering of the mining royalties that are payable to the state from the production of gold.

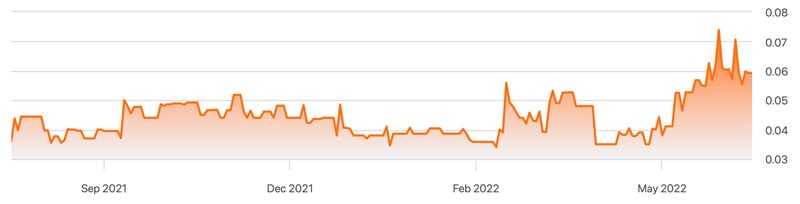

Between October 2015 and August 2016, when the first wave of speculation about a forthcoming judgment made its round, Rusoro Mining stock rallied from 2 pence to 25 pence. In late 2018, when renewed speculation arose that a deal was coming, it quickly quadrupled from 5 pence to 22 pence.

Rusoro Mining.

Over the past three months, the stock has advanced from 4 pence to as high as 9 pence (currently: 7 pence) in what looks like the early stage of another such wave. If Rusoro Mining was paid 24% of its outstanding claim and had to share 20% of that with its litigation funder, the stock would have to increase in value by a factor of ≈10. In any case, this is a stock with a unique story and massive upside. It's probably just a matter of time before the stock price experiences another speculative run-up because the story resurfaces in the mainstream media. If you want to dip your toes into this investment, don't forget to place your order with a limit only, or even wait a few weeks first in case interest picks up after today's Weekly Dispatch.

Rusoro Mining.

Other ways to gain exposure

Surprisingly, there is a whole swathe of stocks that offer SOME exposure to the Venezuela story.

The problem usually is that the exposure of individual companies is too small (relative to that company's market cap) to make it a pure play or even just a worthwhile investment.

Still, given that the Venezuela story is gaining some traction once again, it's worth that someone publishes an overview of these stocks:

- Ferroglobe (ISIN GB00BYW6GV68, Nasdaq:GSM) is one of the world's leading producers of silicon metal and used to generate significant revenue from its Venezuelan subsidiary. The company gave up its Venezuelan operation in 2017, but it could still own a valuable title to a great real estate location in the heart of the industrial zone of Puerto Ordaz.

- Casino Guichard-Perrachon (ISIN FR0000125585, FR:CAJ) is a French mass market retail group that used to own 100% of a Venezuelan retail operation. In 2010, the Venezuelan government paid USD 690m to acquire 80% of the operation from the French company. To this day, Casino Guichard-Perrachon owns 19.9%, which theoretically gives it 30 stores in prime locations.

- Gruma (ISIN MXP4948K1056, MX:GRUMAB) is a Mexican company that owns an arbitral award against the Republic of Venezuela for the expropriation of Monaca. Gruma Venezuela and a second subsidiary called Demaseca were the second largest corn and wheat miller in Venezuela, operating 13 mills which made up 10% of the group's business. The company wrote off the value of the claim in 2013, but legally still owns it.

- Bank of Nova Scotia (ISIN CA0641491075, CA:BNS) owns 27% of Banco del Caribe, one the leading banks in Venezuela.

- ConocoPhillips (ISIN US20825C1045, NYSE:COP) has a USD 8bn arbitration award against the Republic of Venezuela. On 24 August 2022, a US court confirmed the validity of the claim, which was also backed by the World Bank.

- Chevron Corporation (ISIN US1667641005, NYSE:CVX) is a way to get exposure to both Venezuela increasing its oil production and paying back outstanding debt (see the 6 July 2022 Bloomberg article "Chevron Looks to Revamp Venezuela Oil Pact in Bid to Lift Output" for details).

- Cementos Argos (ISIN COT09PA00035, CB:GRUPOARG) from Colombia claims USD 300m against Venezuela.

- In theory at least, you may be able to gain some exposure through the funds managed by Gramercy Funds Management (though you probably need to be in Gramercy's good books to get any more information). When Reuters enquired about it on 6 July 2022, the company refused to provide further details.

- Other fund managers that have launched vehicles for investing in Venezuelan debt include:

- Copernico Capital Partners in Uruguay.

- Canaima Capital Management in Guernsey, Channel Islands.

- Altana Wealth based out of London and Monaco.

While writing this article, I heard on the grapevine that further Venezuela funds were in the pipeline. Most likely, these will be offshore vehicles aimed at professional private investors and institutional investors.

Outside of investing into such existing or upcoming funds or buying legacy assets, there is also the possibility to play future growth. E.g., the e-commerce company MercadoLibre (ISIN US58733R1023, Nasdaq:MELI) doesn't have an operation in Venezuela, but it has an implied growth opportunity if or when the country opens up. You can read more about MercadoLibre in my 23 December 2021 research report.

The more adventurous-minded investors could even start to look through the stocks listed on the Caracas stock exchange. The market is difficult to research if you are not on the ground, but it entails about two dozen companies in sectors such as banking, chemicals, forestry, mining, utilities, packaging, real estate, and household durables. To gain access to such an illiquid, sanctioned market, you need to contact brokerage firms specialised in pioneer markets (such as Auerbach Grayson or, locally, Grupo Solfin). Be warned, though, the services of such firms are only for institutional investors.

Last but not least, you can check out the various Venezuelan debt issues that are traded on bond markets. However, this market is extremely complex due to the different legal treatment of individual bond issues under the international sanction regimes. Trading is also difficult for private investors, and up-to-date information is anything but easy to come by. Possibly even worse, this is the most-followed segment of Venezuelan assets. It's likely that investors who are far more experienced than you will have already grazed over whatever opportunities there may have been.

Equities are where private investors have a reasonable chance of gaining an edge by doing their own research. The stock of Rusoro Mining has languished despite the recent progress in Venezuela, which implies that small-cap equity markets are anything but efficient.

Many remaining roadblocks and complications

As you will have gathered by now, the story of Venezuela as a destination for investment is as complex as they come.

Yet, it's also a story that has recently started to gain new momentum. The US midterm elections could provide additional political momentum as far as sanctions are concerned, and Venezuela itself has a presidential election scheduled in 2024 as well as a legislative election in 2025. The outcome of it all remains to be seen, of course. Maduro could try and turn himself into a competitive political candidate and win the democratic election, or he could just as well utilise the recent economic recovery to strengthen his iron grip on the country. What we do know, too, is that a crisis can go on for much longer than anticipated. The example of Cuba has long shown that, and as a New York Times journalist put it in his aptly named book earlier this year: "Things Are Never So Bad That They Can't Get Worse: Inside the Collapse of Venezuela".

In amidst all this are the additional complications posed by the shadow government of Juan Guaidó, who is recognised by around 60 countries as Venezuela's legitimate political leader, including the US, Canada and various Latin American and European countries. Other nations such as Russia, China, Iran, Syria, Cuba and Turkey continue to recognise Maduro. Guaidó remains in exile, and he has no control over the Venezuelan state apparatus. Among the side aspects of his peculiar role is the ongoing legal battle over USD 2bn worth of gold reserves that Venezuela holds in the vaults of the Bank of England.

The subject of investing in Venezuela is worth an entire book. For further reading about important developments in recent years, I recommend the 25 July 2022 article "What's Ahead for Venezuela's Crisis?" published by World Politics Review.

So much potential

Undervalued-Shares.com will probably get back to reporting about Venezuela before too long. Too big is the potential provided by the country's potential turnaround, and too large are the likely market inefficiencies caused by the chaos that surrounds Venezuelan investments.

How big could the resulting payoff be for those who got in early?

On 23 July 2020, Real Vision published a video interview titled: "The Sovereign Debt Trade of the Decade".

Lee Robinson of Altana Wealth argued that "there could be trillions of dollars in potential upside for the coming decade in the country that has suffered so much over the last decade."

Generating trillions of additional wealth would have to involve a lot more than sorting out Venezuela's past problems, but it's not entirely outside the realm of possibilities if you take an optimistic stance and look at it with a 15-20 year view. After all, Venezuela has many of the makings for a potentially unusual turnaround:

- With 30m people, its population has critical mass. Much of the population is also highly educated.

- A large number of Venezuela's overseas citizens are university educated and wealthy. The possible return of expats could help fuel a turnaround, just as remittances already do to a significant extent.

- Despite years of neglect, Venezuela's infrastructure (roads, airports, ports) still rivals that of many other countries in the region.

- Neighbouring Trinidad and Tobago operates natural gas liquefaction units, which could make it easier for Venezuela to start exporting liquefied natural gas.

- Its geographical position between North and South America puts Venezuela into a valuable strategic location that is free of international conflicts.

In many ways, it's all there for the taking, if only it wasn't for the politics of the place.

The main risk with such situations is always to enter too early, before the right conditions exist.

Then again, illiquid securities are best accumulated during periods when no one pays attention because the situation is considered hopeless. The stock of Rusoro Mining has been trading sideways for several years, which investors with foresight and patience could have used to build a sizeable stake over time and paying those proverbial pennies on the dollar.

Venezuela has the world's largest pool of contested assets, the world's largest oil reserves, and at least a fighting chance of achieving an economic recovery comparable to a tinderbox reaction.

It's not an easy proposition, but one that will appeal to some and could yet make new fortunes.

Profiting from global turmoil

Companies with growth opportunities not despite the difficulties that the world is experiencing, but because of them? They do exist!

My latest stock pick is set to turn crisis into opportunity. It currently trades above its 200-day average and close to its 52-week high. A sign of more gains to come?

Profiting from global turmoil

Companies with growth opportunities not despite the difficulties that the world is experiencing, but because of them? They do exist!

My latest stock pick is set to turn crisis into opportunity. It currently trades above its 200-day average and close to its 52-week high. A sign of more gains to come?

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: