Metals Exploration’s share price has gone vertical. What’s the key lesson, and which three stocks might be next?

Publicly listed central banks: viable investments?

Central banks print money and are always owned by the government – right?

Not so fast. The world of central banking is more complex than that.

There are five central banks which are listed on a stock market: Switzerland, South Africa, Japan, Greece, and Belgium – all relics from a bygone era when public listings for these banks were the norm rather than the exception.

Is any of these banks worth following more closely?

Switzerland: Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB)

Back in 2000, I watched the de-listing of Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Investors had been able to buy shares in BIS through the stock exchanges of Paris and Zurich. For a bank that was created to serve as a bank to central banks and to foster international financial collaboration and stability, it was a peculiar thing to be listed on the stock market and have private individuals among shareholders. There were other unusual features, e.g. its share capital was based on Swiss gold francs.

In September 2000, the world's central banks decided they had had enough of outside shareholders. BIS offered its remaining private shareholders a price of CHF 16,000 per share as compensation. There were different tranches of shares outstanding, and the offer price was 95%, 105%, and 155% above the last share price of those tranches, respectively.

Legislation that enables so-called squeeze-outs was used to force shareholders to sell. Three of them went to court to complain about both the forced sale and the compensation they received. An arbitration court in The Hague ruled forcing shareholders to sell as legal, but granted them an additional compensation of CHF 9,000 per share based on a fair value opinion about the share's intrinsic value. In effect, this doubled the premia that shareholders received compared to the last share price.

Inevitably, the combination of an unusual company, a thinly traded stock, and the overnight doubling of a share price caught my attention at the time.

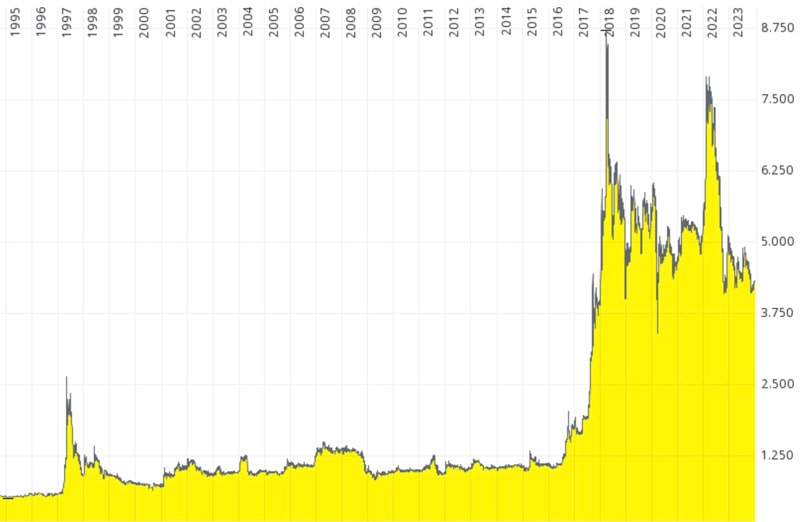

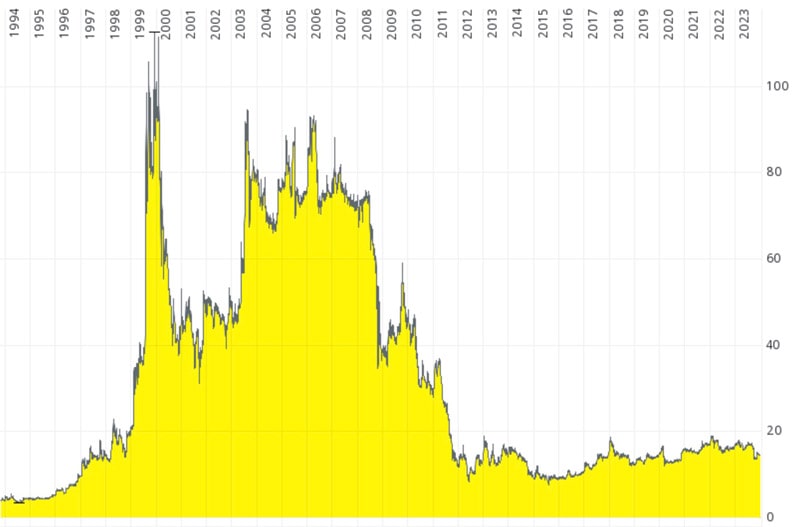

A few years prior, I had already watched the share price of a comparable stock, Schweizerische Nationalbank (ISIN CH0001319265, CH:SNB), briefly go through the roof. SNB is the bank that prints the Swiss franc, and in 1997 its stock shot up from CHF 600 to CHF 2,600.

Schweizerische Nationalbank.

What attracted investors to the stock were the bank's massive gold reserves. Switzerland has one of the world's largest national reserves of gold, and 1,040 tons of it are held by SNB. Given that SNB only has 100,000 shares outstanding, each share of SNB theoretically gives you ownership of 10.4kg of gold with a current market value of over USD 60,000. However, the stock is trading at just CHF 4,300 (USD 5,000). Prices were different at the time but the ratio was similar. Naturally, this makes anyone's ears perk up. Why is the stock so seemingly undervalued relative to the value of its gold reserves?

The answer lies in SNB's special legal status and its corporate statutes.

In 1897, the Swiss held a referendum on whether they wanted a government-owned central bank. Being naturally suspicious of the government, the Swiss voted "no". Instead, in 1907 they set up a "privately owned" central bank. Private shareholders ended up owning 37%, Switzerland's cantonal (= regional) governments about 40%, and cantonal banks 12%. The stock was listed on the Zurich stock exchange for trading.

SNB's office in Bern (image by Michael Derrer Fuchs / Shutterstock.com).

To describe SNB as a privately owned bank is a bit misleading, though. On the one hand, it is a PLC that is listed on the stock market and has private shareholders. On the other hand, its statutes make it more of a state-owned enterprise:

- 90% of profits are transferred to the government.

- The dividend was capped at 6% of the nominal share capital, which equates to CHF 15 per share.

- In the case of a liquidation, shareholders would only get back the shares' nominal value of CHF 250. Any remaining assets would go to the state.

As the bank that has the privilege of printing Swiss francs, SNB was never going to be a normal bank. Shareholders knew about this right from the start, and anyone who bought into the IPO in 1907 would have done so to buy a stock that was effectively equivalent to government bonds.

Even though these rules were spelled out clearly right from the start, in 1997, the rumour of the day was that SNB shareholders were going to get some kind of participation in the gold reserves after all. However, even back then, this was "fake news" disseminated by a bunch of investment newsletters intent on manipulating the share price.

The complete clarity as to who benefits from the bank's assets (and who doesn't) didn't stop one German investor from buying into SNB in a big way. Theo Siegert, the heir of an 18th century family fortune in Düsseldorf, built a stake of up to 6.7%. SNB limits the voting rights of individual shareholders to 0.1%, which made the purchase so remarkable.

Siegert, who rarely speaks to the public, probably concluded that he had spotted an investment case with an asymetric risk/reward ratio. He would have bought the stock in the early 1990s at prices of probably around CHF 500. The stock had a guaranteed dividend yield of 3% p.a., and it was as safe as houses. There was also always at least a tiny chance that the bank's legal status could change one day.

Indeed, by now, Siegert will have benefited from several waves of speculation about possible changes. The biggest of these waves so far took the share price from CHF 1,200 in 2015 to CHF 8,700 in 2018. After Switzerland's dramatic upward revaluation of the Swiss franc in 2015, SNB started to print additional currency at a large scale and use it to buy foreign assets. This move was designed to prevent the Swiss franc from appreciating even further, which would have hurt Swiss exporters.

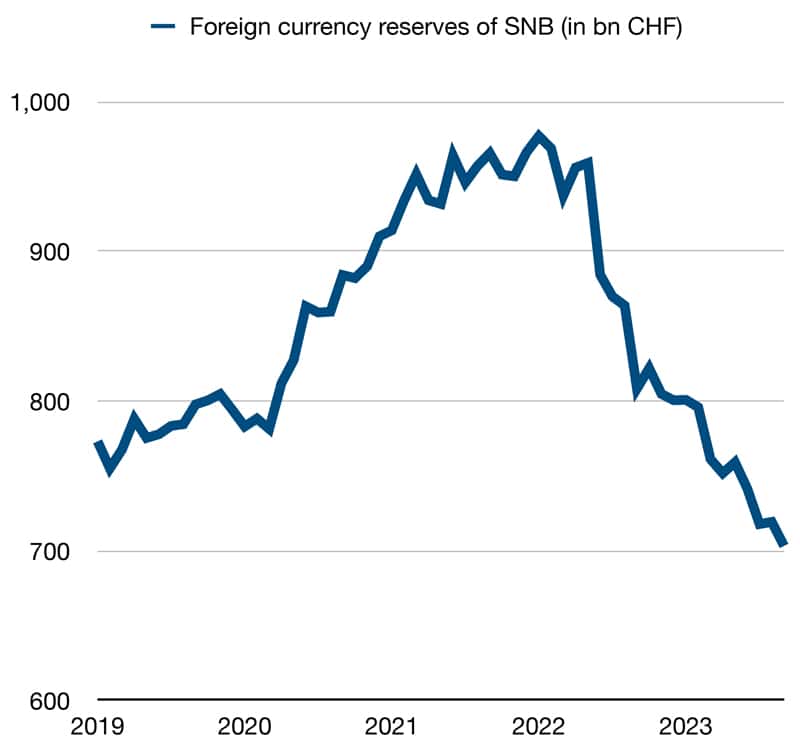

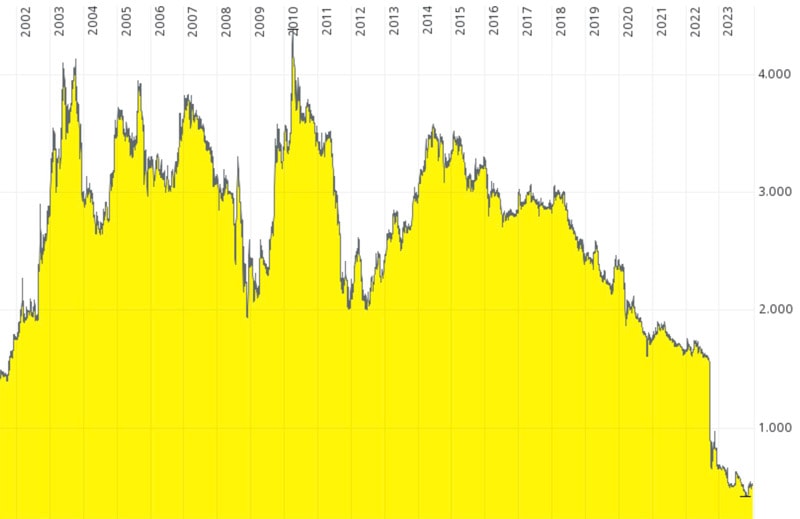

Foreigner snapping up the freshly printed Swiss francs led to an asset accumulation of over CHF 1,000bn at SNB, up from CHF 50bn in 2008. At one point, SNB became the eighth-largest investor in US equities, and it also bought up large amounts of bonds and other assets. With the recent change in bond markets, these reserves have come down somewhat (see chart below), but they remain at a significant CHF 875bn (in comparison, SNB's market cap is a paltry CHF 430m).

Foreign currency reserves of SNB.

If SNB shareholders were ever to get any kind of financial participation in these assets, the stock price would go through the roof. Each SNB share would then be worth MILLIONS – or so the rumour goes. Of course, central banking in general and SNB in particular don't work like this. If anything, the excess assets would flow to the government.

The one scenario I wondered about was whether SNB shareholders could receive a lucrative offer, BIS-style. After all, isn't SNB's public listing a nuisance for the bank and the government?

In fact, in 2003, several members of Switzerland's parliament did raise the case for taking SNB private. This came at the time when a number of laws pertaining to Switzerland's central bank were updated. However, the speculation came to nothing.

Reading through the large body of material that is available about SNB, I concluded – somewhat disappointedly – that a going private wasn't likely in the future, either. Given its peculiar base of external shareholders, an offer would have to be very high to convince enough of them to sell (so that the remainder could be forced to sell through squeeze-out legislation). The government would have to spend hundreds of millions to satisfy the demands of investors that the public will view as "speculators" and "profiteers" – some of them foreign, even! How is a government supposed to justify that when it has the theoretical right to liquidate the bank and pay outside shareholders just a nominal amount of CHF 250 per share?

Not entirely unsurprisingly, even SNB hardcore investor Theo Siegert at one point decided it was wise to reduce his holding. After holding his stake for about three decades, he used the 2017/18 run-up to reduce his stake from 6,700 shares to currently 5,000 shares (5%). Presumably, he will have received his original investment bank several times over, and now owns the remaining stake "for free".

SNB is a fascinating company to read about, all the more since its rapid asset accumulation of recent years. If you fancy falling down a rabbit hole, take a look at the 2021 scientific paper "Wenn eine geldpolitische Nebensache zur politischen Hauptsache wird: Das riesige Vermögen der Schweizerischen Nationalbank" (English: "When a monetary policy side issue becomes the main political issue: the huge assets of the Swiss National Bank").

Will SNB stock ever be a worthwhile investment?

There'll probably be further waves of speculation, if only because it's such an evocative story set in a world-famous country and combined with a thinly traded equity. Some may also see SNB as a kind of safe-haven investment, similar to keeping gold in a Swiss vault. Remarkably, the bank has paid a constant dividend of CHF 15 per share for every year since 1921.

Last but not least, it's a fascinating stock to own for anyone who likes to combine equity ownership with following a company out of intellectual curiosity or visiting its shareholder meeting. Being an SNB shareholder could be a good way to start educating yourself on how central banking works.

What's more, you could even do a Theo Siegert and buy up a stake in a publicly listed central bank while its stock is still little known. For that, you need only about USD 3,000 (!) and a trip to….

South Africa: South African Reserve Bank (SARB)

Siegert must have rubbed his eyes in the early 1990s when he realised that he could purchase 5% of Switzerland's venerable central bank for then not even CHF 3m.

In South Africa, the publicly listed central bank currently has a market cap of just USD 536,000 (not a typo!). The value of all outstanding shares of South Africa's central bank is less than the price of a two-bedroom apartment in London.

South African Reserve Bank / SARB (traded OTC by the bank itself) was set up in 1921 to centralise the note-issuing that had been done by several private banks up to this point. Its history is more impressive than you might expect. It was modelled on the Bank of England, and it was only the fourth central bank established outside of Europe. It's also Africa's oldest central bank.

SARB imposes the following limitations on shareholders:

- No shareholder is allowed to hold more than 10,000 of the outstanding 2m shares. This isn't a restriction on votes that would allow you to buy more shares and then simply not be able to use your votes (as Theo Siegert did), but an actual restriction on the level of ownership. In 2017, SARB forced shareholders with a higher number of shares to sell, which suddenly made 7.5% of the bank's share capital available for a placement.

- The dividend is fixed at 10% of paid-up capital, with the remainder of any profits going to the government. This makes for a dividend of ZAR 0.10 compared to the recent share price of ZAR 5, i.e. a 2% dividend yield.

- Private shareholders can only elect seven of the bank's directors, with the remaining eight directors chosen by the country's president.

Clearly, this is another case where ownership in a central bank is completely separated from control of the bank.

Worse even, there is a seemingly non-stop debate about nationalising SARB. In 2017, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) called the private ownership structure "a historical anomaly" and resolved to nationalise the bank.

Nothing of this nature has happened yet, but it will have contributed to SARB's low market cap. In fact, the bank's element of private ownership has been a bone of contention ever since it was set up. Another South African party even called for expropriating shareholders without compensation. All of this was extensively analysed in "One hundred years of private shareholding in the South African Reserve Bank", a scientific research paper published in 2021.

Mind you, SARB also isn't overly good at its job. As a central bank, it is supposed to watch out for the stability and solidity of the financial system. However, since 1995, the value of the South African rand has dropped 80% compared to the US dollar. SARB isn't exactly a beacon of central bank success.

This hasn't kept a growing number of investors from buying into the bank, though. Over the past five years, the number of shareholders has risen from 600 to now over 800. You don't need a South African brokerage account to buy the stock, but you have to fill out forms, get some of them notarised, and take physical delivery of the share certificate. Further information is available from SARB's website, and you can also check current bid/ask prices and recent trades.

Still, wouldn't it be tempting to use just USD 3,000 to buy the maximum 0.5% stake that you are allowed to own?

Maybe, just maybe, there'll be a wave of speculation one day, similar to what happened to SNB in 1997 and post-2015.

Of course, I am only half-serious.

The half of me that is serious about it will point to recent developments in…

Japan: Bank of Japan

It does seem to be a bit of a running theme in the world of publicly listed central banks that the stocks become a plaything of speculators. It also happened fairly recently to the Bank of Japan (ISIN JP3699200006, JP:8301), a stock that was first listed in 1949 and 55% of which is owned by the country's government.

Set up in 1882, this bank was created to end the practice of Japan's feudal fiefs all issuing their own money in an array of incompatible denominations. Out of these reforms came the Japanese yen. The Bank of Japan was also at the heart of the 1980s financial bubble, which created so much wealth that Japan still lives off it today, to some extent. The Bank of Japan sits in Tokyo's Nihonbashi district, on the site of a former gold mint. Speak of symbolism!

The country of Japan famously is a bit of a closed book, and researching the Bank of Japan is rather challenging indeed. The bank does provide an annual report in English, but across 114 pages of its 2023 edition, "shareholder" isn't mentioned once. Instead, right at the outset, the report speaks of "subscribers", primarily to explain the limitations of ownership:

- Owning a share does not entitle you to participate in the bank's management.

- In the case of liquidation, shareholders will only receive the originally paid-up capital of JPY 100 per share.

- Dividends are limited to 5% of the share's nominal value, or JPY 5 per share.

Does all this sound familiar by now?

During the heydays of the Japanese stock market bubble, Bank of Japan stock was reportedly in high demand by Japanese investors who wanted to own a physical certificate of the bank to hang on their wall. Publicly available charts date back to 1993, when the stock was trading at JPY 350,000. Today, it's down at JPY 26,000. Still, that's 260x the value that shareholders would receive if the bank was wound down.

Bank of Japan.

Along the way of its lingering illness, the stock experienced several spikes. The one that received the most publicity outside of Japan was the 2021 spike when the stock more than doubled almost overnight. It got caught up in the meme stock craze of the day, but only briefly so. Similar to the case of SNB, speculation arose if Bank of Japan shareholders could one day benefit from the massive pile of financial assets that the bank had accumulated over the decades. Among other things, it owned the majority of Japan's outstanding bonds and a hefty portfolio of exchange traded funds.

Source: Bloomberg, 1 March 2021.

Since then, it's gone back to its former record-low, but not without ANOTHER mini-spike in mid-2023. The Bank of Japan also has equity investments, and with the renewed international interest in Japanese stock, someone will probably have published an article about the thinly traded stock.

This particular central bank is also synonymous with a two-decade failed effort to stop falling prices. If there was an investment case for the Bank of Japan, I will have failed to spot it. Do drop me a note if you know a solid reason why anyone would invest in the Bank of Japan for anything other than intellectual interest!

One case that did make much more sense to me was that of…

Greece: Bank of Greece

The Bank of Greece (ISIN GRS004013009, ATH:TELL) is much more of a "normal" bank, in the sense that it is allowed to pay a variable dividend depending on how much money it made that year.

This relative freedom to let outside shareholders participate in its profits would have contributed to the stock's steady rise in the 1990s. In the run-up to the new millennium, Greek stocks benefited from the prospect of joining the euro in 2001. Between 1995 and 1999, Bank of Greece stock went up 25-fold from EUR 4.50 to EUR 112.

This was more than just a brief run-up. The stock still traded at around EUR 75 when the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 hit. The subsequent near-default of Greece's government hit Greek bank shares hard, and Bank of Greece stock fell as low as EUR 9 in 2015. It hasn't done a lot since. Given that Greece is a European country, it seems remarkable that its central bank would trade at a market cap of less than EUR 300m.

In a curious twist, in the case of the Bank of Greece, it's the government that has a limitation on ownership, rather than private investors. The government of Greece is not allowed to own more than 35% of the bank's share capital. However, this was upped from 10% previously, and it is sufficient to give the government de facto complete control of the institution.

The old saying is that a central bank is only as sound as the country it is in. In that sense, it'd be worth investigating in more detail if the Bank of Greece could experience a re-rating soon. After all, Greece recently regained its rating as investment-grade country, and the stock exchange in Athens has been receiving a lot of attention lately for its undervalued shares.

Source: Politico, 21 October 2023.

As part of its recovery, the government of Greece has begun to sell down stakes that it acquired in banks during the financial crisis. UniCredit recently bought Greece's stake in Alpha Bank, which is 100% owned by Alpha Services and Holdings (ISIN GRS015003007, ATH:ALPHA). Its stock, which does show up as "Alpha Bank" in some systems, is up 50% this past year. The government also decided to sell its stake in the confusingly named National Bank of Greece (ISIN GRS003003035, ATH:NAGF), which led to an oversubscription of over 6x for the recent EUR 1bn placement of shares. The National Bank of Greece stock is up sixfold since 2020 and 65% just this year.

The Bank of Greece stock, on the other hand, is down 20% this year and has only gone sideways during the past ten years. Like other banks with massive bond holdings, it will have suffered losses on its portfolio when interest rates rose.

Bank of Greece.

What makes the Bank of Greece potentially more interesting than its peer is its dividend policy. The bank guarantees a dividend of 12% of the share's nominal value, which equates to EUR 0.64 per share. It can pay an additional dividend based on remaining profits. Before the country's financial crisis, the bank paid out up to EUR 40m in additional dividends. Between 2001 and 2010, it paid dividends in the range of EUR 1.98-3.23. It's no wonder the stock was trading at over four times its current price.

Could it ever get back to such pay-outs?

That's the million-dollar question which will move the 17,000 existing shareholders and anyone who is considering to fetch a ride. With other Greek bank stocks already having taken off, could the Bank of Greece be the late runner that is all the more worthwhile to invest in now that other Greek banking stocks have already provided a clear trend?

The bank's annual report also doesn't contain the word "shareholder" once, and the link to share information that you find on the bank's investor relations website yields blank fields for vital metrics such as earnings per share.

It's a stock that someone with more experience in Greece and local contacts would have to research in more detail – but it may just be a worthwhile effort. If you are planning to dig in more deeply or happen to have a Greek auntie or uncle who works in the bank's C-suite, please let me know. I'll dispatch a bottle of ouzo right away to get a conversation going.

Just as much, someone who does dig deeper into this sector should also take a closer look at…

Belgium: Banque Nationale de Belgique

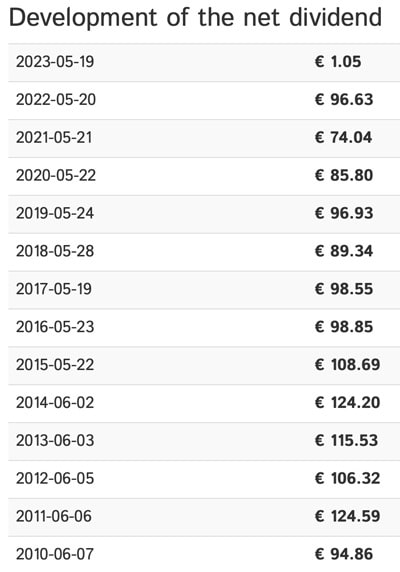

Cut from the same mould as the Bank of Greece, the Banque Nationale de Belgique (ISIN BE0003008019, Euronext:BNB) is able to be quite flexible in its dividend policy.

The bank has to pay a fixed dividend of 6% of the share's nominal value, or EUR 1.05 per share. It can also distribute a flexible dividend, provided its directors decide that these additional funds are not needed to feed into the bank's reserves.

Just like SNB, the Banque Nationale de Belgique sits on a veritable treasure trove of gold, bonds, and other investments. Relative to the size of its small population, Belgium has one of the world's highest amounts of gold owned by the state, and held through the central bank which in turn is 50% government-owned. Activist investors once tried to claim that shareholders owned the gold rather than the state, but a Belgian court gave them a clear and distinct "no" as the answer.

What did work to the favour of shareholders in recent years was the steady income from the bank's investment portfolio, further aided by the situation of negative interest rates. Between 2010 and 2022, the owners of those 200,000 shares that are not owned by the government received an annual dividend in the range between EUR 74-125 per share.

Sadly, the 2023 dividend had to be cut to EUR 1.05 per share. Steep losses on the bond portfolio forced the move.

Source: Banque Nationale de Belgique.

As a result, the stock of Banque Nationale de Belgique is now trading at its lowest level since 1975.

Banque Nationale de Belgique.

Depending on your view of interest rates and bond prices, there may or may not be a case for investing in this beaten-down stock. In that sense, the stock of Banque Nationale de Belgique remains true to what publicly listed stocks of central banks were originally intended to be. They are probably more closely related to bonds rather than equities.

Unless, of course, something ever changes as far as their legal status is concerned.

Could they, will they?

Based on my one day of research, nothing that I found made me believe that anything will change for these central bank stocks.

It was a fascinating journey, though, thanks to excellent source material such as this 2019 article on ownership structures of central banks published by Bank Underground, a blog written by staff at the Bank of England. You could also do worse than treat yourself to the Investopedia article "What Is a Central Bank?"

The last time the world saw significant changes to the ownership and operation of central banks was the wave of nationalisations during the 1940s and 1950s. Until the 1930s, there were at least 30 publicly listed central banks, and they were a widely known asset class. The central bank stocks still listed today are relics frozen in time, and quite likely to remain so.

Unless there are factors that I haven't spotted yet?

If you feel that I've missed a trick, please do let me know!

The world's cheapest oil stock?

Two years ago, Undervalued-Shares.com featured a stock that was "in the top 1% of the cheapest stocks in the world."

With an EV/EBITDA multiple of 2.2, Pampa Energía was as cheap as they come. Today, the stock is up 200% – such is the power of buying into assets at extremely depressed valuations!

The latest Undervalued-Shares.com research report features a stock that is valued at an EV/EBITDA multiple of 0.3 (!) based on 2025 estimates.

There is a catch – but one that should be resolved sometime after February 2024.

Until then, it's worth considering to buy into this opportunity while no one is paying attention.

The world's cheapest oil stock?

Two years ago, Undervalued-Shares.com featured a stock that was "in the top 1% of the cheapest stocks in the world."

With an EV/EBITDA multiple of 2.2, Pampa Energía was as cheap as they come. Today, the stock is up 200% – such is the power of buying into assets at extremely depressed valuations!

The latest Undervalued-Shares.com research report features a stock that is valued at an EV/EBITDA multiple of 0.3 (!) based on 2025 estimates.

There is a catch – but one that should be resolved sometime after February 2024.

Until then, it's worth considering to buy into this opportunity while no one is paying attention.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: