During the final weeks of the year, it's an obligatory exercise to predict what the next year may bring.

Firms like Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, UBS and Credit Suisse have already published their "Outlook 2023" research reports.

How useful are these voluminous, impressive-looking documents in real life?

They take weeks or even months to produce but all too often, they miss their targets by a wide margin. Cynics would remark that they are barely read by anyone. Indeed, it's an open secret that the research departments of large banks primarily send these reports out to promote their brands and find new clients.

Still, this is the season to be reflective and consider the future.

I sourced one such outlook from the long-distant past – the 22-year-old millennium prediction issue of the Wall Street Journal. 1 January 2000 was a very special day that compelled many of the best and brightest to write about the future. "The Journal" – arguably the world's premier newspaper on all things financial, right beside the equally important Financial Times – did as much.

What was on peoples' minds at the time, how has the world evolved relative to these predictions, and what can we learn from it all now that we enjoy the glorious benefit of hindsight?

Here are my three key learnings.

A special issue predicting the future

Those of you who were around at the time will remember the turn of the millennium as one of history's most hyped-up moments.

The WSJ celebrated the occasion by publishing a special issue dedicated to analysing the likely future, covering "such far-flung issues as the future of war and the future of the kiss".

The issue is fascinating to read even today, and well worth spending the ≈USD 25 that you need to pay for a hardcopy on eBay (there are usually a handful of copies available).

Journalists asked:

- "What are the investment options for the future?"

- "Is there really a 'New Economy'?"

- "Are our bodies becoming obsolete?"

The paper's editor conceded the "imponderability of the future", but he wanted to produce a special issue that would "stay on readers' coffee tables for a couple of tomorrows and turn into an antidote to the next dose of hype".

What did this level of ambition lead to at the time?

When reading the following section, keep in mind that the year 2000 was seven years before the unveiling of the iPhone!

"Private Internet 'currencies' may replace government notes"

Did you seriously think that Bitcoin, invented in 2008 as a result of the Great Financial Crisis, was the first attempt to have a digital currency replace that dreaded government fiat?

It's actually a much older story.

As the WSJ reported on the first Saturday morning of the new millennium:

"Government-backed notes will increasingly vie for wallet space with private Internet 'currencies' that are already cropping up with units like 'Flooz' or 'Ubarter dollars'."

The issuers of these currencies described themselves "central bank of the Internet".

There were "exchanges" to switch between different Internet currencies.

One company was even listed on the stock market: DigiCash, an electronic money corporation founded in 1989, offered a software that allowed making electronic payments which were untraceable by the issuing bank, the government, or any third party. In a way, it was a spiritual predecessor of both Bitcoin and the gamut of service providers that now exist to service the crypto industry.

I remember writing about DigiCash at the time, and I bought into its stock on at least one occasion. This was THE company seemingly destined to revolutionise the use of digital money, having first gained the backing of Deutsche Bank, and later Credit Suisse and Visa. Bill Gates offered the company USD 100m to be allowed to integrate DigiCash into his software platform. For some time, DigiCash had been a high-flying stock on Nasdaq and a widely known name, at least in finance circles.

As this example shows, the idea to use encryption and the Internet to replace government money has been backed by investors for a long time. Indeed, the investors of the time were betting on "a grand technofuture of unprecedented efficiency".

Does it all ring familiar?

However, as the WSJ also noted: "the transition to that world may not be so easy".

Much-hyped DigiCash never managed to achieve truly broad adoption. Its founder turned down Microsoft's offer because he felt it undervalued his work. In retrospective, not taking that fork on the road may have ultimately cost him the company. In 1998, DigiCash had to file for bankruptcy. Its remnants were sold to another company, eCash Technologies, which in turn was acquired by InfoSpace in 2002 – which in turn was dissolved later.

22 years later, the idea to use cryptography to create a currency that governments can't mess with is still (or "again") a promising, albeit controversial theme.

Will it manage to eventually transform financial services?

It probably will, but today's investors should keep in mind that they are not as avantgarde as they may think. Previous generations had already put lots of money on schemes that promised an imminent transformation, but they all proved a costly case of being too early – not just by years but by DECADES.

Being too early is a common flaw with predictions. Being too early is something I confess to as well. It's been a lifelong problem of my work, and the reason why I advise anyone and everyone to use Undervalued-Shares.com for inspiration only (or to mock me in private emails and public tweets – as this chap did recently).

In a way, I am glad to see that my failings are not too dissimilar from those of the WSJ.

The upside is, this makes it quite worthwhile to check back to older predictions, as they may have become more imminent in the meantime. Often enough, seemingly outdated predictions contain gems of information that you can now use to your advantage.

Looking at "failed" (= delayed) predictions of the past can be one of the best ways to figure out what may happen in the foreseeable future. This was true back then, and it'll probably remain true until the end of time.

"Investing for the new millennium"

How to invest money for the long haul?

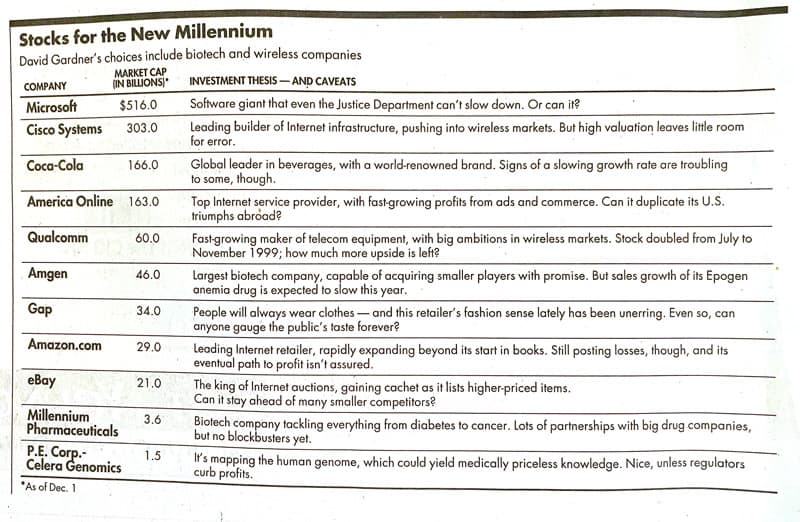

This is a challenge that investors of each generation face. The WSJ tried to be helpful by asking an expert to assemble a portfolio "that would best suit the lifetime needs of a newborn this week".

So how would a 22-year-old stand financially if their parents had set up a USD 100,000 brokerage account for them during those exciting first days of the new millennium?

Here is the portfolio the WSJ suggested.

Source: WSJ, 1 January 2000 (click here to download the entire article as a scan).

Of the 11 stocks:

- 1 merged and disappeared off the stock market (America Online -> Time Warner).

- 1 was acquired outright for cash (Millennium Pharmaceuticals).

- 1 disappeared in a set of complex mergers (P.E. Corp. Celera Genomics).

- 8 are still listed in their original form.

Accounting for stock splits and other capital measures, here is how the portfolio would have performed:

USD 100,000 invested on 1 January 2000 and held until 13 December 2022

| Company | Performance |

| Microsoft | +264% |

| Cisco | -33% |

| Coca-Cola | +66% |

| America Online* | -70% |

| Qualcomm | +125% |

| Amgen | +219% |

| Gap | -85% |

| Amazon | +3,082% |

| eBay | +10% |

| Millennium Pharmaceuticals** | +144% |

| P.E. Corp. Celera Genomics*** | -56% |

| Portfolio value: | USD 424,696 |

| Total return: | +325% |

| S&P 500: | +198% |

* Merger with Time Warner (2001) and sale of Time Warner (2018)

** Sold for cash in 2008 (assumed not re-invested)

*** Sold for cash in 2011 (assumed not re-invested)

A good return, for sure.

The WSJ's expectations had been higher, though.

"Dow 100,000? There is no reason to think this trend (the long-term outperformance of stocks, 11% p.a. since 1926) won't continue. … If historic returns stay on track … the Dow Jones Industrial Index, which darted past 10,000 this year, could break the 100,000 barrier in the year 2024."

With its model portfolio, the WSJ wanted investors to outperform the index.

The stocks that the Journal picked in early 2000 represented some of the most widely held convictions among investors, such as:

- E-commerce was going to conquer the world.

- Biotech and genomics were going to tackle everything from cancer to diabetes.

- No one could slow down Microsoft.

Some of them proved right, but some of them were wide off the mark. Of the 11 picks, just 4 (!) outperformed the Standard & Poor's 500 Index and 3 lost the majority of the capital invested.

"People will always wear clothes." Try telling that to the long-suffering shareholders of Gap who are down 85% thanks in no small part to the changing nature of retail.

"Amazon is still posting losses and its eventual path to profitability isn't assured." Indeed, when you exclude its hosting business (AWS), it took until 2017 for the company to reach profitability. Remarkably, the stock has risen 30-fold regardless.

There is an important lesson you should take home.

A stock portfolio can withstand few bad judgments, provided you land ONE major win every decade.

In my 35 years of involvement with the stock market, that's one of the most enduring lessons I have come to realise are true. ONE outlier winner from a stock that does well can change your life – literally.

The WSJ's millennium portfolio proved as much with its foresightful pick of Amazon. That USD 100,000 portfolio would now set up its lucky owner for their education or a property purchase. Heck, they could even fund their crypto start-up to transform the nascent-again crypto payment industry.

You just have to find one – but you have to find it!

These outlier performers are what motivates me to hunt for promising stocks around the world. Get one such outlier once a decade, and you'll outperform the market even if 64% of your portfolio doesn't even keep up with the main index and you've got more than one big loser in the mix.

Futurology itself

If I reviewed the past 230 Weekly Dispatches that I have published since September 2018, quite a few stunning, embarrassing and amusing misassessments would come to light.

Reviewing past predictions always makes for a humbling experience.

As the WSJ wrote:

"Those who predicted what the future would look like were often wrong. Here's a look at some of the hits and misses:

1965: 'In the year 2000, a national information computer-utility system will take form with tens of thousands of terminals in homes and offices hooked into a giant central computer providing library and information services, retailing, ordering and billing services, and the like.' – US Government, Commission On The Year 2000

1966: 'Remote shopping, while entirely feasible, will flop – because women like to get out of the house, like to handle merchandise, like to be able to change their minds.' – Time magazine

1982: 'By 2000, more than 1,000 people live and work on the moon, a slight majority of them female.' – NASA"

The think tank behind the WSJ's special issue conceded as follows (and yours truly fully agrees):

"What can we learn from these predictions? Little, alas, about which methods work best. Even among thousands of predictions spanning thousands of years, no clearly superior technique emerges.

Yet, a number of conclusions are evident.

First, present trends almost never continue. Straight line extrapolation, perhaps the most common form of prediction, may also be the worst method. Extrapolations have variously foretold the end of all oil supplies, catastrophic overpopulation and federal deficits that would engulf the economy. In reality, trends almost always generate their own countertrends. Societies are unbelievably adept at adapting.

Second, every prediction suffers from situational bias. That's when predictions are influenced by the time period in which they were made. The futurists of the 1950s could easily imagine astronauts working on the moon, but not their own wives working outside their home.

Third, distance and objectivity are powerful virtues in making predictions. Trade associations and political ideologues make notoriously poor predictions within their own domains. Those who came closes to the mark about the year 2000 were professional futurists and detached from commercial interest and political points of view (through their record, too, is anything but perfect).

Fourth, though we are not very good at predicting the future, we are extremely good at creating it!

That raises a final point: that however outlandish, fallacious and inaccurate the exercise, predicting the future widens our horizons and deepens our capacity to imagine."

With these wise words in mind, Undervalued-Shares.com will refrain from publishing its own "Outlook 2023".

What it will continue to do next year, however, is to help you:

- Generate ideas that you would not find anywhere else.

- Understand the world a tiny bit better from a different perspective.

- Hopefully, even have a little fun along the way.

Last but not least, I'll keep hunting for potential outlier investments.

Speaking of which – and at the risk of engaging in the dangerous business of predictions – you may be interested in the investment case of Swatch Group. It's a fascinating investment indeed, and one where I dare to predict that it could have an upside of 2-3 times.

A defensive investment for difficult times

Watchmaker Swatch Group could be worth 2-3 times its current share price if only it got a proper shake-up. If a recession comes, that would probably even help the investment case.

Will the stock ever break out of its lull?

Right now, the market values this possibility at zero, but shareholders could be in for a surprise.

My latest stock pick!

A defensive investment for difficult times

Watchmaker Swatch Group could be worth 2-3 times its current share price if only it got a proper shake-up. If a recession comes, that would probably even help the investment case.

Will the stock ever break out of its lull?

Right now, the market values this possibility at zero, but shareholders could be in for a surprise.

My latest stock pick!

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: