Metals Exploration’s share price has gone vertical. What’s the key lesson, and which three stocks might be next?

Copper – a looming shortage?

Will copper be the next surprise winner among industrial commodities?

There are ominous signs:

- Goldman Sachs is predicting "the end of the copper surplus".

- Trafigura, one of the world's largest commodities trading firms, warns that "the world is running low on copper".

- The copper price has started to rise, even during talks of a potential recession.

If these predictions turn out to be accurate, copper may soon face a structural repricing. Actual shortages, or just simply strong demand, could drive the widely used metal to a new record price altogether and keep it there for years.

What is driving this trend? Why will it come as a surprise to many investors? What are the risks for these predictions not working out as expected?

Copper is the world's third most mined metal, and offers a wide variety of financial instruments to bet on its price. Yet, younger investors in particular are not very familiar with commodities investing.

Today's Weekly Dispatch takes you on a whirlwind tour of everything you need to know about copper – its past, present, and likely future.

"King Copper"

We live in a day and age when most people don't know where things they use and consume on a daily basis come from, or what it requires to produce them. (I admit that I count among them, for the most part.)

It's worth starting an analysis of the copper market by revisiting its very first uses in human history.

Copper is not just any metal. In many ways, it has been one of humanity's best, longest-standing friends.

Copper was one of the first metals ever extracted by early humans, with its earliest documented human use around 10,000 years ago. From 8000 to 3000 BC, it was the only metal well-known by humans in different parts of the inhabited world. Even though it was principally used for making amulets and jewellery, its users already got to appreciate the material's distinctive combination of traits. Copper could be easily stretched, cast and shaped. The fact that it resists corrosion was a bonus.

Around 3000 BC, copper helped to give rise to a new era of humanity's development. When it was discovered that copper can easily be mixed ("alloyed") with tin to make bronze, it indirectly kicked off the Bronze Age. By that time, copper was used for producing tools, weapons, armour, and household items.

Ancient Egyptians used copper to disinfect wounds and surgical tools.

During Roman times, copper was alloyed with zinc to produce brass, which, in turn, enabled the production of Roman coinage. During the Middle Ages, the use of brass was expanded to musical instruments and early mechanical devices.

In the 1800s, the British Navy found that copper sheathing protected the wooden hulls of its boats from rot.

During the 1830s, another discovery led to what is copper's best-known modern-day role. Copper is a great conductor, not just for heat but also for electricity. Samuel Morse, the namesake of the Morse code, built the first model of his telegraph using a few metres of copper wire wrapped in cotton wool. Once it had been figured out how to send electricity through several miles of copper wire, messages could be sent across long distances. For the first time in human history, long-distance messages no longer required physically carrying the message to its recipient.

Not too long thereafter, the invention of the telephone and the electric light bulb significantly expanded the use of copper. These modern-day conveniences only became possible thanks to copper wiring, which forms the basis of our modern electricity grid.

Copper is everywhere in daily life.

Gold may widely be seen as the king of metals, but some argue the crown should really go to copper, given its broad utility. Despite the lack of popular media attention, it's the backbone of our civilisation.

What's more, it might just gain an even more prominent role over the years and decades to come.

A metal that is already all around you

Copper is much more essential to modern life than is generally appreciated:

- Your average family home requires 181kg (400 pounds) of copper. Thanks to its antimicrobial properties, it is an ideal choice for plumbing.

- Your average combustion engine car includes 30kg (65 pounds) of copper.

- Without copper wiring, there would be no electricity grid.

Because of its broad variety of uses, copper is the third most mined metal in human history. It is outdone only by iron and aluminium.

If those who are promoting the use of so-called renewable energy get their way, copper's role as a servant of humanity could reach an entirely different level altogether.

When members of the public think of commodities and renewable energy, they often think of lithium, first and foremost. Because of its use in batteries, lithium has become the posterchild of the energy transition. However, copper could be even more central to these plans.

Our existing energy infrastructure already uses a whole lot of copper. However, what is now being proposed and promoted to reach the so-called Net Zero goal is predicted by many to require copper on a different scale.

An electric vehicle requires 2.5 times as much copper as a vehicle with a combustion engine.

The production of energy from solar and offshore wind needs two times and five times, respectively, more copper per megawatt of installed capacity than power-generated using natural gas or coal. An offshore wind turbine requires around eight metric tons of copper per megawatt, roughly four times as much as a gas-fired power plant. Technology is constantly evolving, and wind turbines as well as solar panels have already seen a reduction in copper intensity, but they still require massive amounts of it.

Electrification requires more copper because of the infrastructure that transports electricity. Copper features superior electrical conductivity and low reactivity, which is why it is used for cables, transistors, and inverters. A bigger use of electricity to power the world will require more investments in the grid.

You can argue about the wisdom of the energy transition. What is difficult to argue with is that the cult-like movement that calls for the electrification of the economy will only succeed if there is enough copper available.

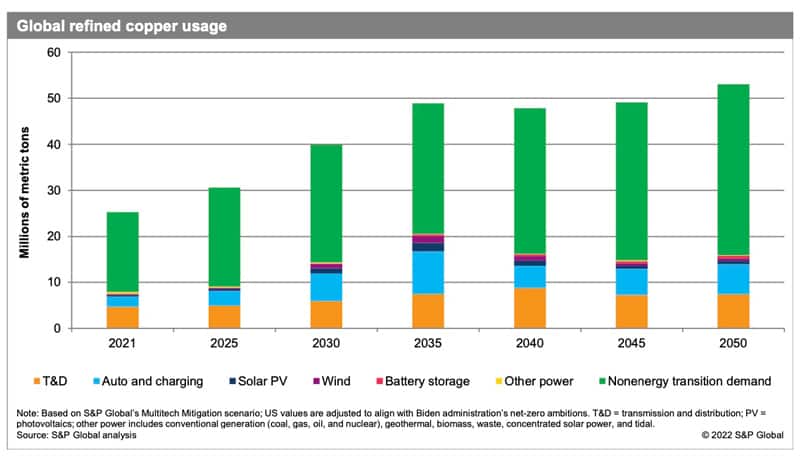

Current estimates for the future use of copper assume that the metal's annual consumption will double from 25m metric tons in 2020 to about 50m metric tons in 2035. This may be too high an estimate, and there are voices that predict that there will be new technological solutions that will allow to use lithium rather than copper (as Elon Musk predicted in a recent tweet). Still, for now, no such technology has been put to use at scale.

If these goals are to be reached, the world better get mining copper.

Source: S&P Global.

The difficulty in mining more copper

Locating and mining copper used to be fairly easy. After all, even the Neanderthals could do it.

The Earth contains vast amounts of copper, and humanity has so far only mined about 12% of the copper contained in the reachable parts of the Earth's crust. Copper fields that are already identified but not mined yet make for about 2.1bn metric tons of available resources, which would be sufficient to supply humanity's needs for 84 years based on current consumption levels. There are probably another 3.5bn metric tons awaiting to be discovered. In theory, we've got enough copper available to us.

However, it's a different question altogether how much of that copper can be mined using today's technology, at feasible costs, and taking into consideration the political realities of the world.

In the late 19th century, the rocks dug up to mine copper used to contain about 5% copper. At the time, even copper mines with grades as high as 10% were not unheard of.

Today, the rocks pulled out of copper mines typically contain less than 1% copper. To end up with the kind of 99.95% high-grade copper that most industrial products require, these rocks have to be ground into concentrate, then smelted and refined, followed by further processes.

The significant deterioration of ore quality indicates the size of the challenge that humanity is facing.

For the world to reach anywhere near the amount of copper production that would be needed based on current technologies and current plans for electrifying the economy, the copper industry will have to be ramped up like never before. Meeting this expected demand growth will require to develop and open three new "tier-one" mines each year, every year for the next 29 years (for a mine to be a tier-one mine, it has to be large, long life and low cost). At today's cost, about USD 500bn would be required to open these mines. The world would have to open the first additional tier-one mine this year when in reality, it nowadays takes closer to 15 years to develop a new mine. In many parts of the world where nimbyism is rife, opening a new mine is extremely difficult politically, bordering on impossible. Following years of self-proclaimed "ethical" investors putting pressure on the financial sector, we now live in an era where banks and investors are shy to put money towards any project that involves digging deep holes into the Earth. Never mind the fact that the world does not have enough well-trained mining engineers, nor enough captains of industry that have the guts to push for making it happen.

During 2002-2011, the mining industry discovered 82 new copper deposits of at least 500,000 metric tons. From 2011-2021, the number of newly discovered copper deposits declined to just 12.

Where is all the copper going to come from then?

It's a question that will affect both the viability of the energy transition plans and the copper price and the profit margins of those who do have the mines ready to produce large quantities.

The risk of the "Net Zero" industry falling

Just about everything is politicised these days, and the predictions for copper demand are no exception.

When research reports and media articles predict a massive increase in copper demand, they usually assume that the special interest groups behind the "climate change" narrative will have their way.

If they do, it'll add about 21m metric tons of annual copper demand by 2035. Within the predicted doubling of copper demand from 25m metric tons to 50m metric tons, the proponents of electrifying the economy will make up the biggest part.

Will they, though?

Maybe. They clearly are pushing very hard. Much of the West's uniparty political system of indistinguishable politicians, the permanent bureaucracy that serves them, and the corporate-controlled media that protect them are on their side. This movement has a lot of support.

Still, success is not guaranteed.

There is no historical precedent to achieve the increase in copper production that is needed to enable such a rapidly growing use of copper. Based on the prevailing set of forecasts for copper consumption between 2022 and 2050, the world would have to produce more copper during this period of 28 years than all the copper consumed by humanity during the preceding 120 years.

Given the forces that are pushing against developing and financing new large-scale mines, how likely is it these targets will be met?

During the past few months, the underlying narrative has started to show a growing number of cracks. We had long been told that combustion engine vehicles were today's equivalent of horse-drawn carriages (e.g., in this infamous YouTube video from 2017), but it's now showing that demand for electric vehicles is not quite the exponential success story that it was predicted to be. Following the failure of earlier, much-touted 2016 predictions that we'd see "millions" of self-driving cars on the road by 2020 (Elon Musk), we may now see a similar cooling down of predictions for an electric vehicle boom.

In 2023, Europe is expected to produce 12m electric vehicles. That is a million cars less than earlier estimates. Rising energy costs, supply chain shortages, inflation, taxes – there is a whole raft of factors weighing on demand. That's before addressing the range and performance problems that many of these vehicles continue to experience. Combustion engine vehicles remain the workhorse of the automobile industry – pun intended.

On 22 December 2022, after a particularly bloody day for electric vehicle stocks, Seeking Alpha headlined: "EV stocks slump into 2023 as investors eye profitability over green energy dreams". As energy realists will have known all along, no industry is immune to the sobering aspects of reality. There is a limited number of people who buy electric vehicles at any cost because they need them for their personal branding and public virtue signalling, or buy them out of curiosity because it's something new. For the other 99% of humanity, factors such as cost still play the crucial role, and their main concern is to get from A to B.

It remains to be seen just to what degree electric vehicles will become a dominant force within the global car market, and when. It's worth remembering how the European Union once encouraged drivers to buy diesel cars. During the 1990s, diesel cars were heavily promoted – and subsidised – as a more fuel-efficient alternative to help stave off so-called global warming. This was widely cheered on at the time, but it turned out there were many unintended consequences. Today, the EU is proposing a ban of such cars by 2035. Speak of a U-turn.

Source: Daily Mail, 27 January 2023.

The electric vehicle boom could still turn out to be a temporary hype, or something that (as I suspect) unfolds over three to four decades. If the growth curve for the electric vehicle industry had to be adjusted, it would lead to a downwards revision of estimates for the future consumption of copper.

Still, the special interest groups that are pushing for these changes are not to be underestimated. Also, for the avoidance of doubt, there are some legitimate arguments in favour of a partial electrifying of the world's infrastructure. E.g., in big cities, where air pollution is more of an issue, promoting and even subsidising electric vehicles could make perfect sense. In any case, this industry, and the changes it promotes, is almost certain to stick around to some extent. How fast (or slow) it advances is a matter for discussion.

Also, it's ultimately just one of the factors that drive demand for copper.

Even if the idea of electrifying the West's economies was put back into the drawer, demand for copper would still be rising.

The metal that humanity cannot do without

The analysis of copper demand trends is currently dominated by the so-called energy transition. However, the truth is that demand for the chestnut-coloured metal will likely increase one way or another, even if the world does not transition to Net Zero.

There is growing demand for constructing buildings, producing appliances and electrical equipment, creating mobile phones, and enabling new applications in areas such as communications or data processing (where copper is used for circuits on microchips). Leaving all talk of an energy transition aside, copper demand would probably continue to grow at an annual rate of 2.4% between 2020 and 2050.

This seems like a relatively small increase, but even that will be difficult to match with increasing supply. The many years of underinvestment in the mining sector, driven also by prevalent environmental concerns and nimbyism, are now starting to show an effect.

Quite probably, from 2025 onwards, the world will have to face up to an unprecedented shortage of copper supplies. It's long been talked about, but now seems about to happen. The recent increase in the price of copper could turn out to be a precursor of it – or the first leg up, ahead of further legs up that are yet to come. (And the reopening of China's economy could further accelerate it.)

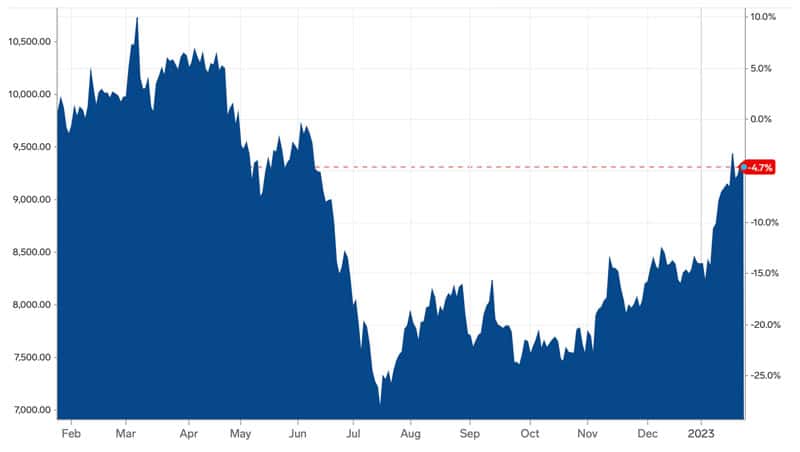

The copper price (source: Markets Insider).

A looming copper shortage?

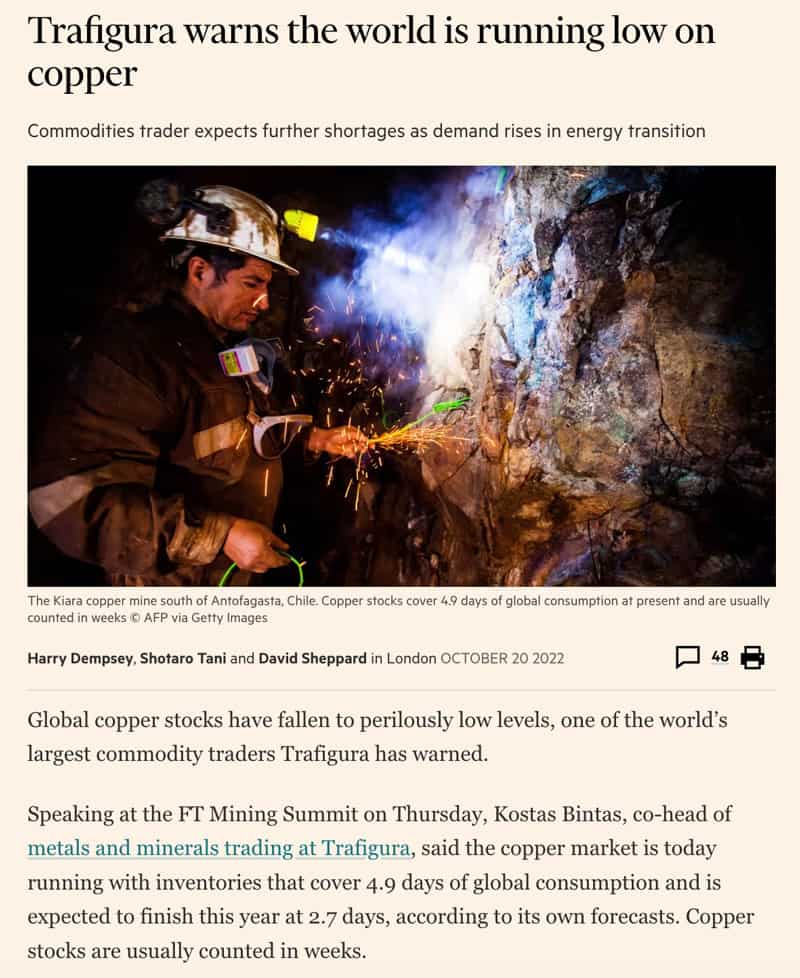

On 20 October 2022, the little-known but gigantic commodities trading firm, Trafigura, warned that "the world is running low on copper".

As the Financial Times reported back then:

"Global copper stocks have fallen to perilously low levels. ... Speaking at the FT Mining Summit on Thursday, Kostas Bintas, co-head of metals and minerals trading at Trafigura, said the copper market is today running with inventories that cover 4.9 days of global consumption and is expected to finish this year at 2.7 days, according to its own forecasts. Copper stocks are usually counted in weeks."

Source: Financial Times, 20 October 2022.

This could be a sign of things to come, and it will likely come as a surprise to many.

Not too long before Trafigura's warning, copper traders had braced themselves for a period of oversupply. From a high of USD 10,800 per ton in March 2022, the copper price fell as low as USD 7,000 a short four months later. The market was spooked by an oncoming period of plentiful supply, driven by factors such as a cyclical peak in actual supplies from the mining industry and softened demand from a locked-down China.

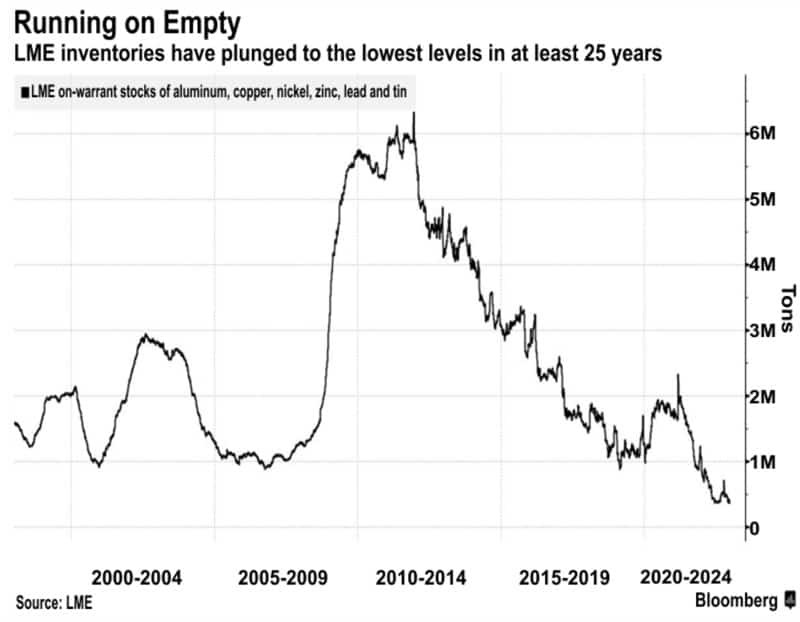

Another few months later, it became clear that fears of oversupply were exaggerated. Copper is back at USD 9,300. In a 6 December 2022 research report about the global copper market, Goldman Sachs' commodities experts concluded:

"Copper: The end of surplus

Over the past year, copper investors have been consistently reminded that between 2022 and … the middle of the decade lies a period of surplus, as a final burst of mine supply temporarily softens fundamentals.

Yet today, this soft patch is failing to materialise, … with global visible stocks falling to the lowest level in 14 years, both critical factors curtailing downside risk to price, in our view. Moreover, the surplus we previously expected for 2023 (169kt surplus) has also now disappeared in our latest balance iteration (GSe 178kt deficit). The tightening increment primarily reflects a sharp downgrade in global mine supply expectations for next year (-434kt vs Oct-22 balance), with the projected growth rate falling by a third over the past quarter to just 3.6%, as well as significant upgrades to China's renewable related demand (+250kt vs Oct-22 balance). Moreover, with copper mine greenfield and brownfield project approvals having plunged to cycle lows this year, peak supply is now immovably fixed in mid-2024, reinforcing open-ended depletion generating deficits from that point."

From 2025 onwards, the confluence of forces that is shaping the copper market could create an extraordinary situation unlike anything this market has ever seen before:

- Between 1994 and 2024, the largest ever shortfall of copper amounted to 2.5% of that year's copper demand.

- Based on current estimates for copper demand, the supply gap will reach an unprecedented 9.9m metric tons or 20% of global demand by 2035. The shortage will start to bite in earnest from 2025 onwards, which is now within sight.

It remains to be seen to what degree such a scenario actually materialises. For the most part, gaps between supply and demand don't last. As the saying goes, the best cure for rising prices of commodities are rising prices. Rising prices and outright shortages tend to lead to an increase in supply, a substitution of that metal by other materials, an ongoing decrease in the copper intensity required for some sectors, or outright demand destruction. The electric vehicle mania could grind to a halt because of a lack of copper and become nothing more than another chapter in the history of colourful manias that future generations read about in amazement. There is a possibility that some of the demand for copper will be replaced by aluminium or lithium. Also, new technologies could change the situation altogether in ways that no one can imagine right now.

A seminal, 122-page report about the copper market (available for free – S&P Global).

Still, it seems highly likely that from 2025 onwards, global markets will face an increasing and possibly unprecedented shortage of copper. There is also a significant likelihood that it will last at least for a few years, if not even the following decade.

After all, plans to increase the global production of copper will face headwinds from no less than eight operational challenges:

- Infrastructure constraints, e.g. building or even just maintaining the roads, railroads, and ports needed for the effective and timely transport of copper ore to refineries.

- Permitting and litigation, especially in developed markets. High levels of transparency make it unlikely a new mine will be permitted in less than ten years.

- Local stakeholders, who will demand better participation in the value creation of their domestic copper mines.

- Environmental standards, involving ever-stricter requirements for environmental issues such as the use of water, waste management, and preventing deforestation.

- Taxes and regulations, consisting quite simply of an increase of the tax bills for copper miners. The magic word will probably be "windfall" taxes, as the politically acceptable 2020s equivalent to the 1960s concept of outright expropriation.

- Politicisation of contracts, i.e. the ever-changing regulations for miners and sometimes dramatic changes from one election cycle to another.

- Labour relations, in an industry that has always been and continues to be heavily unionised.

- Industrial strategy, which will likely involve national governments taking an increasingly active role in the economic development of copper resources, given its increasing strategic importance.

As a fun intellectual exercise, think for a moment how these different areas often overlap. The level of complexity that the captain of a mining industry has to overcome to create a new mine are incredible. Is it a surprise that many commodities company CEOs prefer to buy back stock and pay out dividends, instead of doing capital investments? By shying away from opening new mega-mines, they ensure that their wife will come back happier from meeting her soy latte-sipping friends at the local Pilates class and their shareholder meeting won't involve "green" activists rocking up outside. (I wrote separately about how the CEO of British Petroleum once complained in the Sunday Times how "socially challenging" his job has become.)

The odds for opening three new tier-one mines every year for the next 29 years are looking quite optimistic.

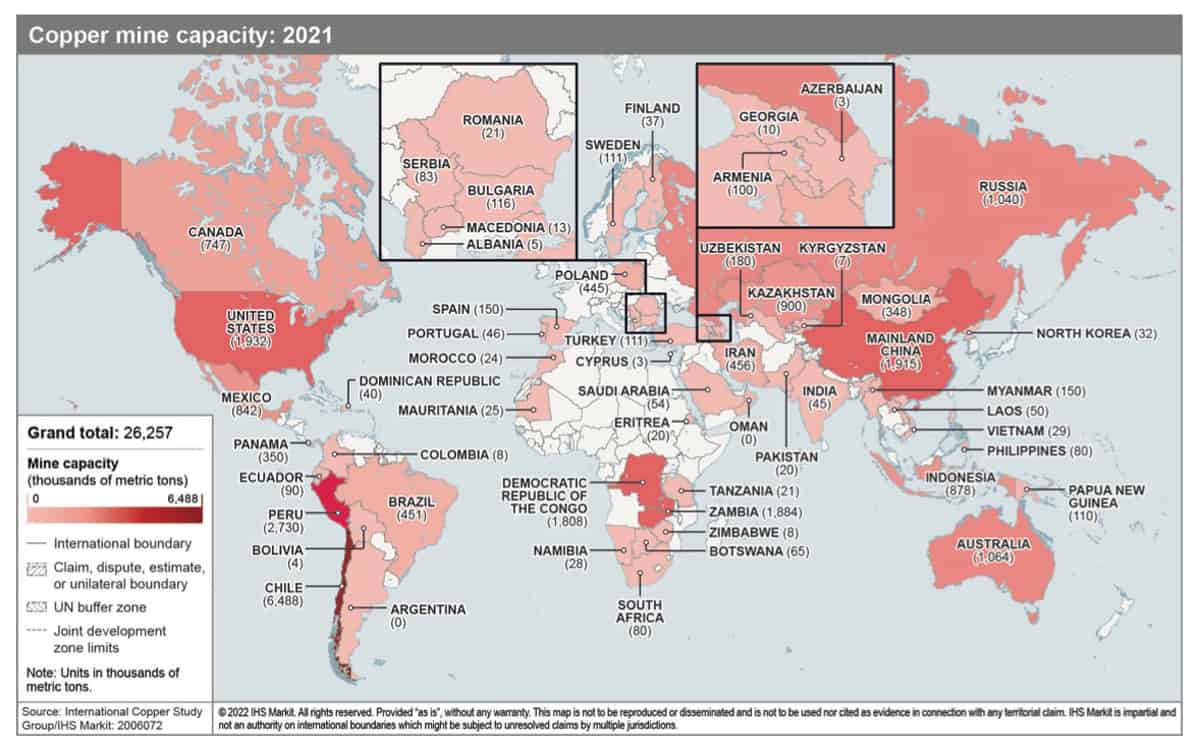

Copper is often mined in problem-ridden parts of the world (source: S&P Global). Click on image to enlarge.

Copper is probably a great asset to own

Given all these challenges, what are the odds for the world to achieve the rapid, massive and unprecedented increase in the production of copper that is required to make current plans feasible?

You be the judge.

The most likely outcome seems to be that we will see a mixture of these potential scenarios. We are unlikely to see the kind of copper shortage that predictions based on current demand estimates and current technologies foresee, nor will we see a quick, smooth path towards new technologies and commodities replacing copper. The chips usually fall somewhere in the middle between such extremes. There'll probably be enough of a shortfall to exert upward pressure on copper prices for at least a good number of years.

In which case, copper-related assets are an investment you should look at.

If copper experiences the kind of "structural repricing" that the circumstances laid out above point towards, we could see a similar re-rating of copper-related stocks as we saw with coal-related stocks in 2022.

Which stock to pick?

I looked at the entire sector, and found one company that you'd be well advised to take a closer look at.

Glencore: the only commodities investment you need

Glencore already accounts for 4% of the world's copper consumption and owns mining assets that allow to more than double its production.

The sheer size of its copper reserves – coupled with their low production costs – makes this company one of the cheapest blue chip stocks for getting exposure to the copper story.

Glencore is expected to pay a ≈15% dividend yield for 2023, it is currently buying back stock at a rate of >10% the daily trading volume, and it has the highest free cash flow yield in its peer group.

Glencore: the only commodities investment you need

Glencore already accounts for 4% of the world's copper consumption and owns mining assets that allow to more than double its production.

The sheer size of its copper reserves – coupled with their low production costs – makes this company one of the cheapest blue chip stocks for getting exposure to the copper story.

Glencore is expected to pay a ≈15% dividend yield for 2023, it is currently buying back stock at a rate of >10% the daily trading volume, and it has the highest free cash flow yield in its peer group.

Over the next three years, Glencore should return 50-60% of its current share price to shareholders.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: