Metals Exploration’s share price has gone vertical. What’s the key lesson, and which three stocks might be next?

Investing in Poland (part 1): Europe’s overlooked growth champion

Name Europe's most consistently growing economy.

Switzerland?

Luxembourg?

Maybe one of the Nordic countries?

Nope, none of the above.

It's Poland.

And that's just one of the many surprises the country has to offer.

For the past three years, I have teasingly referred to Poland as "the new, better version of Germany".

I recently noticed that others have started to agree with me. As you are about to learn, there are some mind-blowing statistics about the country's economy.

Combine that with a few other noteworthy facts for investors:

- One of the cheapest stock markets in the world (based on p/e ratio).

- Nearly 500 listed companies, and another 350 on a junior market.

- The first former Eastern Bloc country to achieve "high-income country" status. Poland is no longer an emerging market but a developed country that ranks alongside its Western European counterparts.

Would you have known?

Let's go on a discovery tour and do a bit of myth-busting along the way.

Read on to learn more about an up-and-coming European destination for equity investments, and how you could make money off it.

We can't do it without – a two-minute primer on Polish history

Any analysis of Poland has to begin with the country's history.

Somewhat unusually, it does require going back at least 500 years (!) to get a full appreciation and understanding of what's happening in the country today.

Much of the contemporary media reporting deals quite critically with the country's current politics and the Polish view of national sovereignty.

I've long swallowed and never questioned these reports until I made a conscious effort to dig into the details. No one had ever told me that over the last 225 years, Poland has been a self-governing country for only 52 years.

In 1795, the country had vanished off the map entirely. Its neighbouring states had partitioned Poland, and it ceased existing.

The Poles were effectively homeless until the Treaty of Versailles in 1918, but they lost their territory again shortly thereafter, to the Nazi invasion in 1939.

During the Second World War, Poland lost nearly one fifth of its people, twice as high as the percentage loss of Germany and 1.5 times as high as that of Russia. When the carnage was over, Poland fell under Communist Soviet rule until 1989.

Once a nation and its people have been through such trials and tribulations, they will have developed their very own view of nationhood.

All the more if there is a mythical "Golden Age" lurking in the background.

Between 1505 and 1648, Poland had enjoyed a period of prosperity, progress, and political stability that put it at the pinnacle of Europe.

At the time, it was one of the largest countries in Europe by landmass. The combined Poland and Duchy of Lithuania (also known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) saw the country stretch from the Baltic coast in the North to the Black Sea in the South and Bohemia in the West. It prospered economically by exporting vast amounts of grain, wood, salt, and cloth through its Baltic sea ports, such as Gdańsk.

Politically, it was the most advanced universal democracy in the world. Nearly 10% of the population – the landed gentry – was allowed to vote in a regional and national parliamentary process. Starting in 1572, they even elected Poland's king.

Polish was the lingua franca of Central and Eastern Europe. Students flocked to the University of Krakow, one of Europe's first universities – founded ahead of the universities of Vienna, Barcelona, and Heidelberg. The country's luminaries, such as Nicholas Copernicus, were part of Europe's academic elite.

Compare all of this with what came afterwards.

Poland's national psyche is heavily influenced by its descent, from one of the most powerful and prosperous countries in Europe, to the continent's poorhouse. Never mind that it even vanished off the map entirely for over a hundred years.

This historical background makes it all the more remarkable just what happened since Poland regained independence in 1989, following Lech Wałęsa's two-decade struggle that saw him become the first elected president in 1990.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its highest territorial extent (1616-1657), superimposed on modern European state boundaries.

The economic rise of New Poland

By the late 1980s, socialism had turned Poland into one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Polish salaries were just one tenth of those in neighbouring Germany. Poland was the second-worst performing economy of the Eastern Bloc, outdone in poverty only by Romania. The country wasn't just financially bankrupt, it also suffered from outdated and inefficient infrastructure and industry. Poland seemed like an unfixable mess.

During my teenage years in Germany in the early 1990s, the #1 running joke about Poles was their perceived involvement in organised crime: "A car that gets stolen today will reappear in Poland tomorrow." (It rhymes in German: "Heute gestohlen, morgen in Polen.")

Evidently, the newly independent Poland didn't exactly enjoy particularly advantageous starting conditions - which makes the performance of the past three decades all the more impressive.

Leaving aside the last four months of pandemic-driven economic trends, here is how Poland has fared in recent history:

- 27 consecutive years of economic growth, averaging 4.2% p.a. from 1992 to 2019 and lifting the per capita income (adjusted for purchasing power) by a factor of 3.

- During this period, Poland has grown faster than:

- All other former Eastern Bloc countries.

- All other large countries in the world with a similar level of income.

- Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea.

- Other historical economic achievements include:

- Europe's longest recorded growth spurt ever.

- One of the most extended growth periods recorded in world history.

- Second-fastest ever rise from poverty to high-income (behind South Korea).

Poland was the only EU country to avoid going into recession in 2008/09 – the Polish locomotive steamed on! It's now the seventh largest economy in the EU, ahead of Sweden. Much as any such comparison is inherently flawed, the country's level of affluence is now roughly on par with Portugal.

Poles across the board nowadays enjoy a higher level of income. There are considerable differences between income groups and regions, but even the poorest Poles have seen their income rise significantly during the past three decades. The tide lifting ALL boats set the country aside from the many other countries that are currently experiencing political challenges due to their disappearing middle classes.

In at least some surveys, a remarkable 80% of the Polish population expressed their happiness with life. Other rankings concluded that it's at least as pleasant to live in Poland than in the much-richer South Korea (based on my personal experience in both countries, I believe this comparison is both accurate and relevant). In any case, Poles nowadays enjoy the same access to global culture, technological progress, and civilisation as their peers in Western Europe.

Remarkably, Poland has achieved this turnaround without any major natural resources at its disposal. Its surrounding continent is the persistent underperformer of the world's three largest trading blocks. Poland didn't even rack up an outrageous amount of debt to fund its growth. At last count, it had a comparatively modest 50% debt-to-GDP (Switzerland: 40%; Germany: 62%; UK: 90%, USA: 105%).

You can argue about details, but Poland has managed the transition from relatively poor to high-income in just a generation's time. It has become Europe's untold economic success story. In 2018, Poland gained the status of "developed country" – up a notch from "emerging market".

Skyscrapers have started to dot the skyline of Warsaw.

The country's size matters

Another aspect that often gets overlooked is the sheer size of Poland's population.

With 40m people living in Poland, the country offers the economies of scale that other Central and Eastern European countries are missing.

Only Ukraine is bigger, with 43m people. However, Ukraine is also one of the poorest countries of the region, so it's not a particularly relevant country economically (plus there's the war).

Following Poland are Romania (17m) and the Czech Republic (11m). These are tiny countries in terms of the overall economy or stock market capitalisation (one of Germany's 16 states, North Rhine-Westphalia, has more residents than Romania).

All other countries in the region don't even scratch the 10m mark. Central and Eastern Europe are heavily fragmented, often with different languages making these markets even less accessible.

The combination of a large population AND much-increased levels of income has turned Poland into a substantial market indeed. It's an economy worth paying attention to.

Given all that, one would expect that investors and fund managers become more interested in investing in Poland.

But not so – at least not yet.

Why the Polish stock market caught my attention

The Warsaw Stock Exchange is home to nearly 500 companies. It's roughly on par with the number of publicly listed companies in France, and compares quite favourably with Germany's 800. Also, there is a junior market segment with another 350 companies.

Despite the respectable number of companies, the overall valuation of the market appears to be very low.

The 300 larger Polish companies that make up the "Main Market" have a combined market capitalisation of EUR 200bn (USD 230bn). That's about the combined value of the two publicly listed German companies Siemens (ISIN DE0007236101) and Linde (ISIN IE00BZ12WP82) which are the second and third largest German companies in the DAX.

You could either own Siemens and Linde outright or use the same amount of money to buy 300 of the largest companies of Poland.

Purely based on intuition, one would view these figures as an indication that the Polish stock market is overlooked, forgotten, and undervalued.

If you look up the five cheapest stock markets in the world, Poland does rank somewhere in there (leaving aside pioneer markets and small countries). Once you delve a bit deeper into details, you can find some Polish blue-chip companies trading at p/e ratios of 5, 4, or even 3.

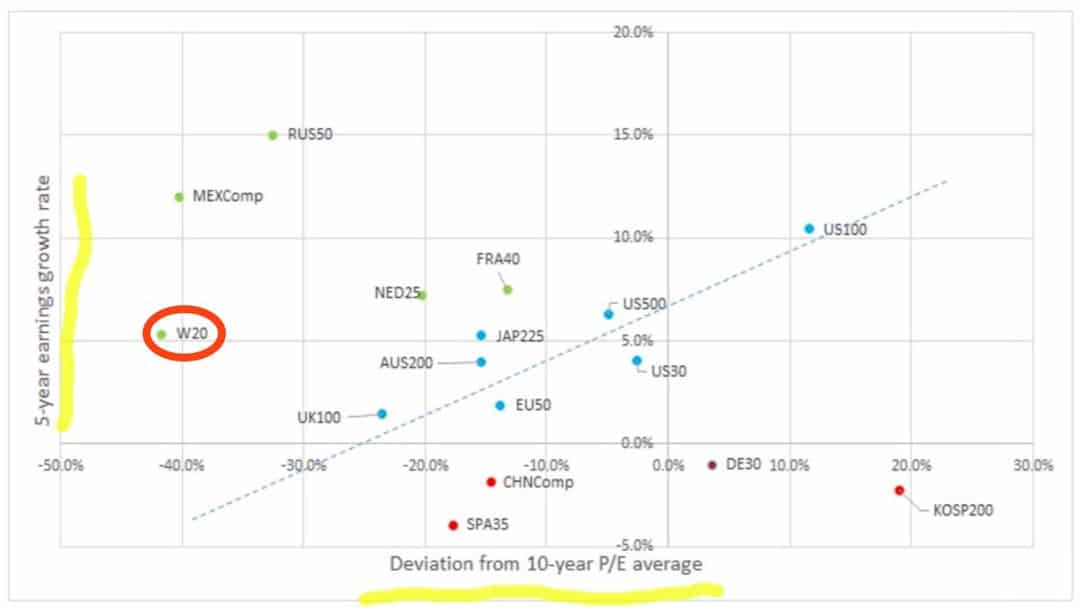

Based on earnings multiples and growth, Poland is one of the world's cheapest stock markets besides Mexico and Russia (overview based on spring 2020 figures).

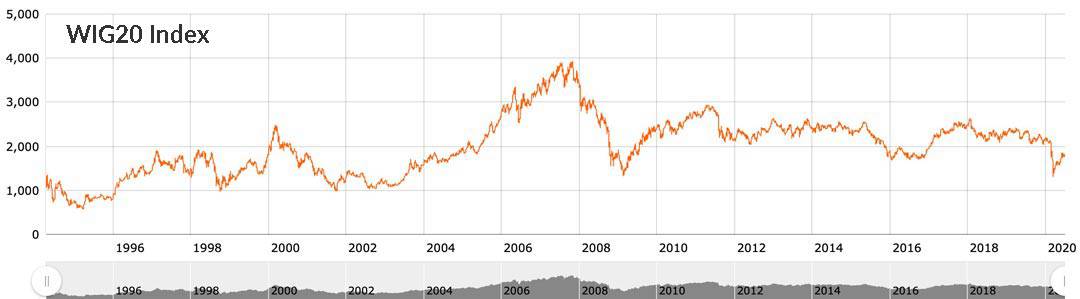

The economic success of the country did not translate into a stellar performance for Polish blue-chip stocks. The WIG20 index is currently trading no higher than in 1996. Over the past decade, the market has not even gone sideways – instead, it has had a gentle decline. During the same period, American equities have rallied, and even most Western European exchanges have reached new all-time highs. From where it's at now, the WIG20 would have to more than double to reach its 2008 high.

Why the laggard performance and decline, and is there any prospect that it could change in the foreseeable future?

Following a two-week stay in Warsaw in spring 2018, I became an interested observer of the country. This three-part blog series aims to give you a first insight into the Polish market, and help you decide whether it's a market worth dipping your toes into.

Equity investors have not yet made money off Polish blue chips.

Widely-known problems and well-established narratives

There are a couple of reasons that appear to make it obvious what's been wrong with the Polish market:

Problem #1: "It's all Old Economy, often state-controlled"

Many of the blue-chip companies that make up the WIG20 and WIG30 indices are Old Economy, and in many cases, the government is a significant (or even dominant) shareholder. Such companies tend to trade at a discounted valuation, whether in Poland or elsewhere.

Problem #2: "Poland is on a disastrous path politically"

There have been long-standing and seemingly never-ending political controversies. None of which is more widely remembered than the 2015 to 2017 conflict with the EU about Poland "refusing to take in asylum seekers" (as the BBC put it). Much more so than in the case of other countries, the international perception of Polish politics has been weighing on the stock market's valuation.

Problem 3: "There is little domestic demand for equities"

Last but not least, Poles aren't interested in the Polish market. Their overall interest in equities is well behind their peers in Western Europe, let alone the US or Asia. Poland has also been lacking a sophisticated sector for pension monies going towards purchasing domestic equities.

These are some of the long-standing, widely-accepted narratives why the Polish stock market has not been able to pick up pace.

However, whenever something appears to be universally known and accepted, I can't help but ask if these views still hold up to scrutiny.

Do they?

I looked at these three factors in detail.

Surprising finds as soon as you scratch the surface

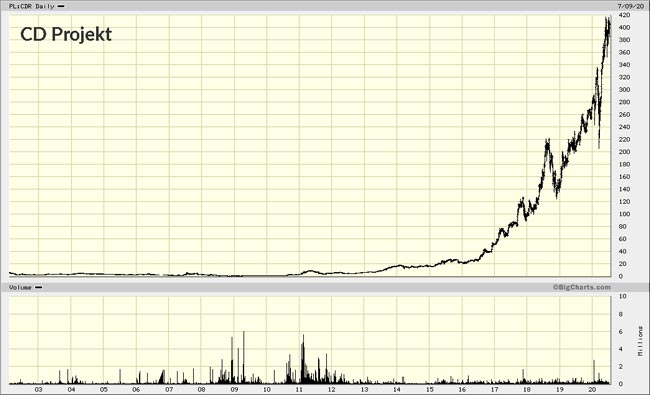

You only need to look through the stocks comprising the WIG20 index, to come across CD Projekt (ISIN PLOPTTC00011), a gaming software developer.

Since 2008, its stock price is up by a factor of 600. The company now has a market cap of USD 10bn.

CD Projekt has minted millionaires.

Is the Polish market really just about Old Economy? Apparently, not so.

Once you start to dig a bit deeper, you come across a burgeoning sector of growth companies in IT, biotech, healthcare, and media. Amidst those, Poland has edged out a particularly strong position in game development – as any good gamer will be able to confirm.

None of which should surprise anyone. Poland has one of the better university systems in the world (ranked among the top 10 globally by some surveys), and its population is highly educated. Nine out of ten younger Poles have been through secondary education. Among the young generation in big cities, speaking English fluently is a given.

Whenever I research a new country, I make an effort to mingle with locals and get a real flavour of the country. To get a better grip of Poland, I attended the Wolves Summit start-up conference in Warsaw, as well as a smaller event hosted by project managers from the software industry (which I wrote an article about at the time).

There is a lot of economic dynamism in Poland, and an impressive next generation of entrepreneurs and managers rising through the ranks.

I spoke to Adrian Kowollik, CEO of East Value Research, a Berlin and Warsaw-based equity research firm with over a decade of experience in analysing Polish small and mid-cap stocks. Here is his current assessment of the Polish stock market:

"The Polish stock market is currently at a very exciting point. While valuations are historically attractive, there is increasing buying activity from the newly-created obligatory pension funds and retail investors, who have returned to the market over the last few months. As interest rates in Polish zloty are almost zero, Poles are looking for higher-yielding investment opportunities for their savings, which reached a record of EUR 260bn at the end of 2019.

All of the above has also reinvigorated the IPO activity in Poland. One of the most exciting companies that announced its intention to list its shares is the largest Polish e-commerce platform, Allegro. Allegro, which is owned by the PE funds Cinven, Permira and Mid Europa Partners, has >21m registered users, 140k professional sellers and displays 130m offers. According to Bloomberg, the company could be worth USD >11bn."

Based on that, there is a lot more to the Polish market than first meets the eye.

The same holds true for politics, where my conclusions are quite different from the established narrative of the mainstream media.

Two sides to each (political) coin

Whenever I visit Warsaw (which I do several times a year, bar the outbreak of pandemics), I am always struck by how different the social scene feels compared to visiting neighbouring Germany.

In Germany, my friends and professional contacts mostly moan about a litany of well-known, never-changing and increasingly toxic problems. Frustrations are running deep, and there is a widespread fear for the future of the country.

In Poland, I don't get such a sense. Quite the opposite, people seem upbeat and relaxed.

The obvious question to ask is whether that's simply down to me getting too narrow a view of either country. Are my impressions shaped by hanging out in bubbles?

Politics is, of course, polarising just about anywhere right now.

It's all the more interesting to take a look at what is probably the most polarising issue Europe is currently facing. It is, of course, that of immigration. Or, as some call it, migration. Or refugees. No one can even agree on the basic term for the issue.

Did Poland really "refuse to take in refugees", as the BBC put it following the EU's legal action against the country?

As it turns out, the BBC's reporting couldn't have been further from the truth. It's an example that is directly relevant for the investment prospects of the country.

Poland actually took in "the biggest wave of migration into the European Union in recent times", as the Wall Street Journal reported in an in-depth piece. From 2014 to 2019, over 2m Ukrainians left their war-torn country and settled in Poland. Relative to the size of the native population, it represents more than twice as large a resettlement programme for immigrants than the one Germany started in 2015.

In Germany, the subject divides dinner tables and even tears families apart. On an economic level, the continued lack of success in integrating the new arrivals continues to cost double-digit billions annually based on the government's own statistics.

In Poland, my observations were very much in line with the Wall Street Journal's reporting. The lack of welfare and the existing cultural compatibility had the Ukrainians integrate rapidly. Financially, Poland benefitted from the additional labour – making up at least to some extent for the many young Poles who left the country in the early 2000s.

Poland resisting international pressure and going its own way provided yet more fuel for the country's economic boom, instead of creating another burden. Outside of economic aspects, it also didn't suffer the destabilising political fallout that immigration-related issues caused in Western Europe. Only 12% of Poles say they are hostile towards the massive wave of immigration, and the remaining 88% view it as positive or neutral.

To each controversial story, there are always two sides.

No one doubts that the predominantly negative foreign media reporting about Poland's politics has so far contributed to the laggard performance of the Polish stock market.

Could the situation eventually turn into the opposite and leave Poland with an advantage?

Avoiding a divisive issue and avoiding a persistent financial burden strike me as a positive rather than the negative that it was often portrayed as. I think the jury is still out for this one. We may yet see another Polish surprise.

The country's political course is an issue that I will get back to in part three of this series, which will deal with the longer-term outlook for the country.

This 15-minute video from VisualPolitik speaks of "Poland as the new Germany" – and racked up 1.2m views. Once you have finished reading my article, it's a MUST WATCH.

The Polish pension money opportunity

My current reading list includes material about the country's ongoing pension fund reforms. Following year-long debate and extensive public consultations, Poland seems to be on the cusp of introducing a pension system that could provide tailwind for the stock market.

Employers of a certain minimum size will have to auto-enrol their employees into a pension plan, dubbed "PPK" in Polish. Crucially, the accumulated assets will be private. Employees will have personal ownership of their pension pots.

The English-language reporting about these ongoing pension reforms has been haphazard, and I've received mixed feedback from local contacts concerning the prospects. Still, it appears like there is at least a decent possibility of game-changing developments regarding Poland's culture of buying domestic equities. Experience shows that privately-held pension savings tend to favour domestic equities.

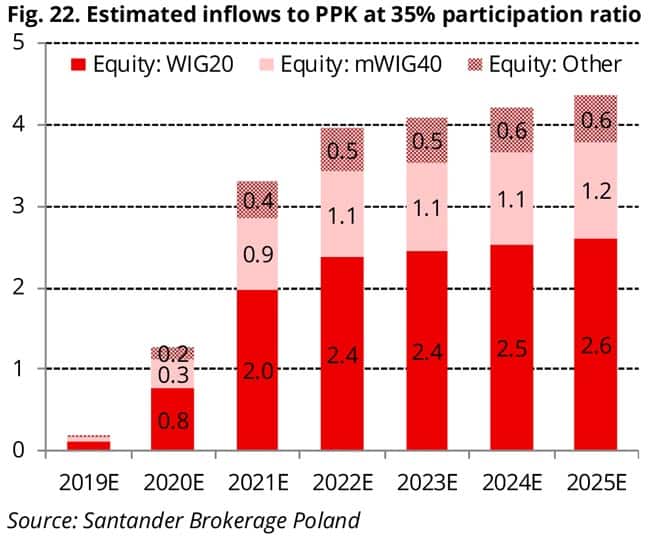

In a December 2019 primer on the Polish market, analysts from Santander tried to quantify the likely effect of these changes on the Polish equity market: between 2019 and 2021, the amount of money invested in domestic equities by Polish pension funds would increase by a factor of 20 – and then remain on a high level going forward.

As some observers put it, these new pension vehicles will be "forced buyers" for Polish equities. Needless to say, they'll have to focus on blue chips because that's where liquidity lies for large-scale buyers.

The estimated inflow to Polish equities from "PPK" pension schemes.

Will Poland's stock market surprise during the 2020s?

Poland has already provided irrefutable evidence of its ability to transform against all odds.

It has turned itself from a perennially backward, poor and peripheral country to a member of the world's high-income countries. It's a story not often told, but the figures speak for themselves. Hardly anyone expected it, but Poland has become one of the most successful European countries of the past 30 years.

Are there more such surprises coming our way?

Will the Polish pension fund reform lead to a wave of excitement about Polish equities?

Could the Polish equity market finally get re-rated by investors, both domestic and foreign?

My interest has certainly been piqued.

However, outside of the pension fund reforms, there are many more questions that I am still investigating.

They include (but are not limited to):

- If the government pushes through its plan to double the minimum wage by 2023, what effect will it have on the country's economic competitiveness? Which sectors will benefit, and which ones will suffer?

- If Germany hits a recession, how will Poland fare? Germany remains the largest economy in Europe, and Poland is the most dependent on it.

- Two days after publishing this Weekly Dispatch, Poland will see the second (and final) round of a presidential election. Polish politics are as polarised as elsewhere. What effect will the outcome have on crucial public policy decisions?

- What are the risks of the country carrying out a "polonisation" (aka nationalisation) of strategic industries? How will a more nationalistic-minded country fare during the coming era of countries looking to secure their crucial supply chains?

Most importantly, though, I want to understand if there are remarkable opportunities hidden in the Polish stock market.

Should investors be looking primarily at Polish growth companies, or are Old Economy companies deserving a closer look?

The Polish zloty has been remarkably stable compared to most of its peers since the Great Financial Crisis. Is the Polish currency a risk for investors, or maybe even an opportunity? Poland's economy is projected to shrink 3.5% this year, but within Europe that would yet again make it the most successful economy.

My sixth sense for changes in the Zeitgeist has detected a shift in sentiment. Three years ago, when I first spent a significant amount of time in Warsaw, most of my friends shook their head in disbelief. Warsaw? Ugly! Polish food? Yuk. Polish stocks? Can't name a single one.

More recently, one of my German readers told me (cited with his permission): "My company has employees in both Germany and Poland. If it wasn't for the language issue, I would have moved to Poland by now. Personally, I now view it as the (much) better version of Germany."

And that's just one of many anecdotes I can offer.

The wider public's perception of Poland is changing, and change brings opportunity.

My next Weekly Dispatch will introduce you to some innovative growth companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. We will be looking at high-tech made in Poland and the publicly listed companies that are driving it.

Stay tuned for more.

Blog series: Investing in Poland

There's more to "Investing in Poland" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Poland has many surprises in store…

… and there's money to be made!

The Polish stock market is one of the world's cheapest, so who am I not to dig into the exciting opportunities that are hiding under the surface?

One of them even made it into one of my latest research reports - a new med-tech champion, destined to dominate the European market in a technology that could truly change the world (and for the better). From Poland!

It's a small-cap, and one of four additional investment opportunities that I make available to my Lifetime Members every year (among other benefits, of course!).

If you, too, would like to access this opportunity (as well as all upcoming ones), I recommend you sign up for a Lifetime Membership. My Lifetime Members are an interesting group to be in, and there is plenty of good stuff coming their way!