Capturing a "100-bagger" is the premier league of investing. In case you didn't know already, the term refers to a stock that rises in value by a factor of 100. That's enough to turn an initial investment of USD 10,000 into a cool million.

It's all the better if such a 100-bagger doesn't take ten or twenty years to compound its way up slowly. Sometimes you can find situations where a stock explodes in value within a few years or even just a few months. These are the investments that everyone dreams of finding at least once in their lifetime.

One investor who had a decades-long history of catching such deals not just once but repeatedly was Adolf H. Lundin. Over four decades of investing and dealing, he managed to build a family fortune amounting to billions of dollars. In one case, he may have even made 500 times (!) his money from bottom to top

Lundin's investment approach?

He focussed on buying the riskiest investments in the most exotic corners of the world, which allowed him to accumulate assets for the proverbial pennies on the dollar.

Lundin died aged 73 in 2006, but there are still many lessons that private investors can draw from his success. Some may even apply to the group of companies that his heirs are now running. The website of "The Lundin Group", as the loose federation of companies is called, lists no fewer than 24 publicly listed companies that are traded in London, Stockholm, Toronto and New York. The combined market capitalisation of the Lundin Group companies stood at USD 21bn at the time I published this Weekly Dispatch. Investors who want to latch on to the Lundin way of investing can buy into a whole range of separate companies, some of which still represent the audacious nature of the family's founder.

Here is part 1 of my new miniseries about making extreme profits by investing in some of the world's most treacherous, exotic countries.

Finding investments where others don't dare to tread (yet)

Adolf Lundin's investing success didn't come overnight, nor early in his life. It wasn't until his 40s that he figured out how to eventually make a fortune. Once Lundin had found the right approach, he used it to make spectacular gains not just once, but repeatedly.

It's all beautifully captured in his 2004 biography, "Adolf Lundin: No guts, no glory". The book has become a collectable, and the few available copies on the Internet (on websites such as Abebooks) generally cost at least USD 100. I have picked out a few excerpts for you.

"As Adolf neared his 40th birthday, he knew that if he did not dare to take big risks, he would never realise the dream of his own business empire. … He also added that he learned a great deal from his early mistakes.

…

In 1969, Adolf and another group of friends started an investment company … Austro International Investment Corporation had a simple philosophy: they invested only in high-risk companies where there was a good chance of reaping major profits. … It is clear on looking back that Adolf's investments were highly speculative, and he thus ran the constant risk of losing everything. There was also, however, an undeniable chance for him to multiply his original investment. For a man who was resolutely determined to … build a business empire worth hundreds of millions of dollars, speculation was a sensible investment strategy."

It didn't take long for Lundin and his co-investors to strike it rich:

"Adolf invested in nickel companies. Among them was Poseidon, now infamous in mining circles. … In 1969, Poseidon's shares rose sharply on the Sydney Stock Exchange, and Adolf was not slow to jump in. On September 21, 1969, Poseidon shares were quoted at 1.85 Australian dollars. Less than four months later, the same shares cost 280 dollars."

Over the following decades, Lundin invested in companies around the world, and often involving destinations that even nowadays would be considered edgy.

"The Lundin Group is looking for new projects in areas where no one else wants to operate because they consider the risks too great."

This approach took Adolf Lundin and his co-investors to some of the most remote, underdeveloped, crisis-ridden, and least-known jurisdictions of the world.

The right book for anyone who wants to learn from the Lundin family's multi-billion-dollar success story.

Frontier market investing in 1970s Qatar

In 1972, Lundin had a chance meeting with an unemployed geologist at Geneva airport. In conversation, while waiting for a delayed flight, it turned out that Lundin's new acquaintance owned copies of unpublished seismic reports from drilling projects in Qatar. These projects had been abandoned, not because they weren't a good prospect, but because of a lack of funding. Smelling an opportunity, Lundin arranged to meet the Emir of Qatar to discuss entering the country and creating a publicly listed exploration company.

The Emir was fascinated by Lundin's personality and storytelling abilities, but negotiations over drilling rights stalled. The Emir was clearly vying for a bribe, but Lundin's US-based corporate lawyers wouldn't have it. To get around the tricky issue, Lundin offered the Emir to personally bet one million dollars that it was going to rain in Qatar the next day. Given that Qatar only experiences rain on nine days each year, he was bound to lose the bet. Lose he did, and the Emir happily signed the corporate drilling concession once the million dollars of Lundin's personal money was in his hands. Given his major shareholding in the company, Lundin could afford to advance his own money.

Subsequent drilling led to the discovery of the world's largest gas field outside of the communist world. Some say that Lundin's work created modern-day Qatar. In any case, it made a fortune for his newly-created gas company, Gulfstream, and its outside shareholders. Had Lundin hesitated because of his lawyers' advice, both his career and the fate of Qatar would probably have looked different.

His biggest coup, though, was yet to come. During the 1990s, the Lundins made hundreds of millions, and possibly even billions at a later stage, by venturing into Russia at a time when few other investors dared to tread into the former communist country.

The ground-floor opportunity of investing in Russia

The early 1990s had seen the Soviet Union dissolve, but this didn't make for an immediate turn in Russia's fortunes or investment prospects.

"During the years following its collapse, there was increasing chaos in Russia and other former Soviet republics. Crime and corruption reached levels that made even the most hardened business executive shy away."

Lundin went in regardless because he felt the extraordinarily low asset prices more than compensated investors for the increased risk.

"From the mid-1990s on, Adolf followed this plan and devoted more and more of his time to the Lundin Group's interests in Russia. … At the time, the valuation of Russian companies was extremely low. Adolf paid 3 million dollars for a 10% stake in Surgutneftegaz, one of Russia's largest oil and gas companies. The valuation was less than a few cents per barrel."

There are different figures floating around when it comes to the Lundins' early investments in Russia. Analysing the history of these investments is made yet more complicated by the fact that Adolf Lundin put his Russian interests into a holding company, Vostok Nafta, which was floated on the stock market and raised money from other investors at different valuations.

It's safe to say that he eventually built a stake in Gazprom, the Russian gas company well-known to Undervalued-Shares.com Members, that amounted to an impressive 0.6% to 1% of the company's share capital. At the time, doing so was still hindered by technical issues – and all the more rewarding for this very reason!

"Through a complicated division of the Gazprom shares into two types, only about 4% of Gazprom was foreign traded. Only Russian citizens and entities could own the local Gazprom shares, while anyone could own deposit certificates traded on the London exchange.

Vostok Nafta was able to buy large quantities of local Gazprom shares through its Russian subsidiaries. The price of these shares was only between half and two thirds that of the price of the unrestricted shares traded on the London stock exchange. Adolf Lundin and Per Brilioth (CEO of Vostok Nafta) wanted the ownership restrictions to be eliminated, as this would lead to a significant rise in the value of the local shares.

In 2002, Gazprom shares comprised more than 80% of the Vostok Nafta portfolio."

Speak of a concentrated portfolio!

No one can say with certainty what profits the Lundins earned on their early Russian investments. Their dealings in Russia involved the publicly listed holding company, separate family members, debt funding and other complications. Also, it's challenging to find reliable historical data on the 1990s prices of locally-traded Gazprom shares.

It seems safe to say, though, that the Lundin Group had made at least 40 times its money (on paper) when Gazprom stock peaked in 2007. Another estimate assumes that from its low after Russia's 1998 credit default and stock market crash (which the Lundins did suffer through), the Lundin holdings in Russia made about 500 times their money over the subsequent 20 years. Per Brilioth may have been one of the best investors that no one has ever heard of.

Whatever the exact multiples were, the Lundins made out like bandits.

Speaking of banditry (whether real or imagined), it's important to note that such extreme investments are also often surrounded by a fair share of political and public controversy.

No guts, no glory – thick skin required!

Following the death of Adolf Lundin, his family and the Lundin Group of companies created a Liechtenstein-based foundation. Funded with an initial USD 2m, the family and the group wanted to celebrate the memory of their founder through philanthropy.

In July 2007, the family made headlines for committing an impressive USD 100m to the Clinton Foundation. The funds were earmarked to alleviate poverty and support sustainable development in some of the countries where the family companies made money.

But were these donations all that they seemed to be?

During the past few years, a debate has been raging whether donations to the Clinton Foundation were a particular form of (soft) corruption. Given the time that has passed since all this happened, a lot more information has surfaced about these affairs. Anyone with an interest in this kind of investing can learn a few lessons about what it takes to succeed in a sector where entrepreneurs regularly depend on politicians in less than savoury countries.

At the centre of this debate was Frank Giustra, a colourful Canadian mining entrepreneur. Over the years, through triple-digit million-dollar donations to the Clinton Foundation, he had become their single largest Canadian donor, and there was going to be a link from him to the Lundins.

When looking at such matters, I prefer to check back on reporting that pre-dates 2016, given how politically tainted much of the mainstream media reporting has become since then. E.g., in 2008, the otherwise Clinton-friendly New York Times reported rather critically about Giustra's uranium dealings in Kazakhstan. It set out how in 2005, Giustra didn't have more than an empty shell company and a plan to invest in resources in the country, whilst being in competition with much larger, better-established companies. What his competitors didn't have, though, was Bill Clinton. Giustra brought the former president along to a meeting with Kazakhstan's (dictatorial) president, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

As the New York Times reported:

"Within two days (of the Giustra/Clinton/Nazarbayev meeting), corporate records show that Mr. Giustra also came up a winner when his company signed preliminary agreements giving it the right to buy into three uranium projects controlled by Kazakhstan’s state-owned uranium agency, Kazatomprom.

The monster deal stunned the mining industry, turning an unknown shell company into one of the world’s largest uranium producers in a transaction ultimately worth tens of millions of dollars to Mr. Giustra, analysts said.

Just months after the Kazakh pact was finalized, Mr. Clinton’s charitable foundation received its own windfall: a USD 31.3m donation from Mr. Giustra that had remained a secret until he acknowledged it last month."

The Washington Post, too, dedicated an extensive 2015 article to the matter. It also mentioned that "the Clinton Foundation acknowledged that an affiliated Canadian charity founded in 2007 by Giustra kept its donors secret, despite a 2008 ethics agreement with the Obama administration promising to reveal the New York-based foundation’s donors."

Honi soit qui mal y pense?

Fascinating reading material for anyone who wants to learn about the overlap of Big Politics and Big Business – whether real or imaginary.

The history of the Clinton Foundation continues to be surrounded by never-ending controversy: overlaps between its fundraising work, Hillary Clinton's unique global influence at the time of working as Secretary of State, and the wheeling-dealing of entrepreneurs who suddenly discovered a generous streak which they felt could only be discharged by making mega-sized donations to the Clinton's family foundation. Neither the twice-failed presidential candidate nor her family foundation were ever prosecuted, but the issue left a sour aftertaste.

Notably, the Lundin's record-level donation wasn't given to just any activity of the Clinton Foundation, but the "Clinton Giustra Sustainable Growth Initiative (CGSGI)".

Does the old saying "You are the company you keep" still hold true?

Records that have turned up in the meantime show a significant number of mining companies donating to the Clinton Foundation. That was, until 2016. In the year following Hillary's failure at winning the presidency and her de facto loss of governmental power, donations to the Clinton Foundation collapsed. In 2014, the foundation had raised nearly USD 173m. In 2017, its income amounted to less than USD 27m.

The late Emir of Qatar could probably have offered an interesting perspective on all of this. Mining companies are infamous for regularly producing headlines about such entanglements, and it can be incredibly difficult to tell apart legal influencing from illegal corruption.

Does it matter for investors, though?

As these goings-on show, investing in ruins is not for the faint-hearted. What's more, there are always two sides to each coin. What some call controversial operating methods and exploitation of vulnerable countries, others view as much-needed investment and development opportunities. Without hard-headed entrepreneurs that go into frontier markets despite all the obstacles presented by these countries' lack of governance standards, many of the world's most desolate countries would stand much less of a chance of ever getting on their feet. And why blame well-intentioned entrepreneurs for the lack of governance standards in other countries?

You be the judge whether this kind of investment approach might be for you, or whether you'd pass because of ethical concerns.

Even today, there certainly is no shortage of investment opportunities of this kind. One of the latest exploration interests of the Lundin Group shows as much. It involves a country that most people would struggle to find on a map, which is infamous for manifold maladies, and where incredible fortunes may soon be earned by some.

Next up – the Guyana plateau opportunity

Writing this particular article had been on my mind since 2006. Back in the days, the former director of a national park in British Guyana told me about the country's long-rumoured hidden treasure – oil!

The three Guianas are countries that long existed off the radar of the world's media. French Guiana, Guyana (formerly: British Guyana) and Suriname (formerly Dutch Guiana) have a combined population of less than 2m. They have persistently ranked among the world's poorest, least developed and most corrupt countries: until the mid-2010s, when the country's oil exploration got into gear, Guyana's score never made it past the high 20s of the World Corruption Index (where a score of 100 represents immaculate standards, and a score of 0 points to hyper-corruption). The country has also been rather infamous as a significant drug smuggling gateway, and for one of the highest crime rates of the region.

Georgetown, where a quarter of Guyana's population lives.

As the New York Times wrote in a 20 July 2018 article:

"Guyana is a vast, watery wilderness with only three paved highways. There are a few dirt roads between villages that sit on stilts along rivers snaking through the rain forest. Children in remote areas go to school in dugout canoes, and play naked in the muggy heat. The power grid is so unreliable that blackouts are a regular plague in the cities, while in much of the countryside there is no electricity at all."

The Guianas may be an obscure part of the world, but they are rapidly becoming better-known. In 2020, British Guyana is projected to achieve economic growth of 86%. That's eighty-six percent GDP growth in a single year – it's not a typo. The discovery of large amounts of oil off its coast will soon have a transformative effect on the country.

Others have gone even further in their assessment. A 9 May 2019 report by the BBC quoted the then-American ambassador to Guyana, Perry Holloway:

"Many people still do not get how big this is. Come 2025, GDP will go up by 300% to 1,000%. This is gigantic. Guyana will be the richest country in the hemisphere and potentially the richest country in the world."

The math behind these extraordinary developments isn't difficult. As the International Monetary Fund worked out, Guyana simply has the highest amount of oil for each individual person of any country in the world: about 3,900 barrels of offshore reserves (in comparison, Saudi Arabia has about 1,900 barrels per person).

Watch this 9-minute video about Guyana's potential economic miracle.

I have followed the subject from afar ever since my local friend had told me about the population's expectation that there was a lot of oil waiting to be discovered. I must have been one of the few people outside of the country who wasn't surprised when staggering quantities of oil were discovered off the coast of Guyana in 2015.

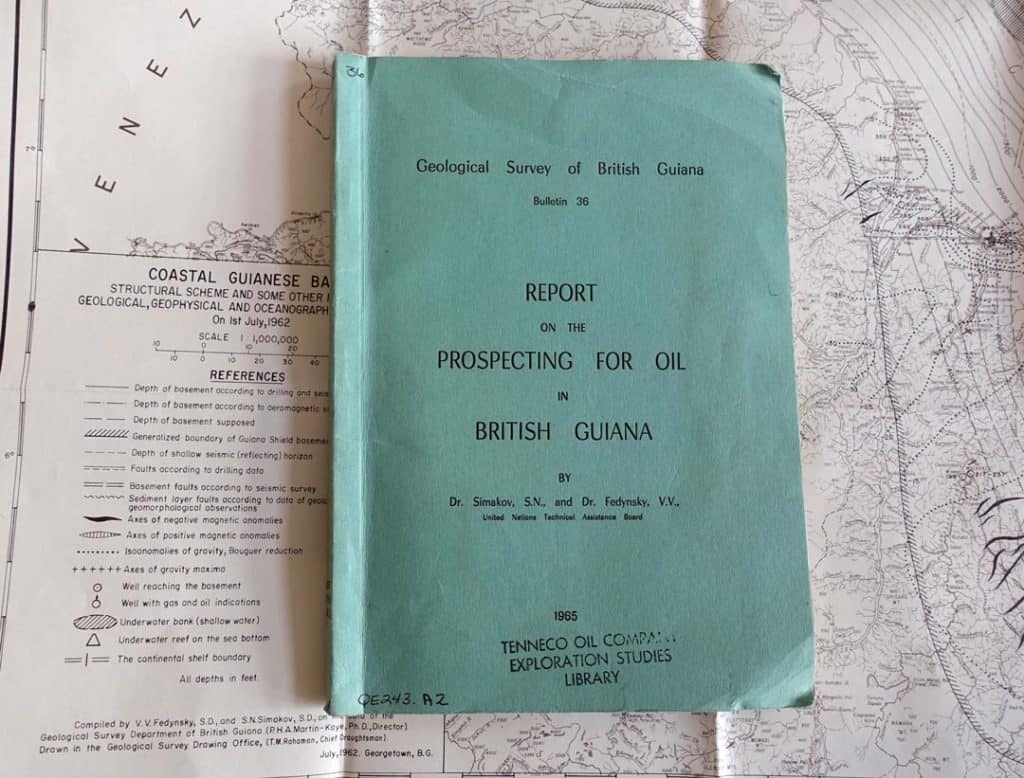

The occurrence of oil in the Guianas had actually been known about for a long time, if only through indicative findings that eventually disappeared in archives. I own a (very rare) copy of the "Report on the Prospecting for Oil in British Guiana", published by members of Britain's Geological Survey in 1965.

Archives and long-forgotten documents sometimes guide you to modern-day investment opportunities.

As the 55-year old report wrote in its opening:

"The first indications that oil might be found off-shore in British Guiana came from reports of the early Dutch Explorers who appeared in that area at the end of the 18th century, and who mentioned the occurrence of flotsam pitch.

…

Dr. H. G. Kugler indicated in his report (1944) that according to the data obtained from the exploration in 1939, oil was likely to be found in the continental shelf of the Atlantic Ocean off-shore British Guiana. …It transpires from the data that there is ample ground for continuing with oil exploration."

However, the tiny, difficult-to-access Guyana simply wasn't worth anyone's while for as long as oil was easily discoverable elsewhere in the world.

The proper exploration of the plateau off the coast of the Guianas didn't happen until the mid-2000s, but it has since led to the discovery of previously unimaginable amounts of oil.

As Bloomberg reported in an extensive 5 November 2019 article:

"Next year, Exxon Mobil Corp. and its prospecting partners will start pumping oil from one of the world’s biggest recent finds: some 5 billion barrels of crude cached in the sandstone deep below the Caribbean floor. The windfall promises to change the energy landscape in the Western hemisphere. Guyana may never be the same.

In five years, national output is expected to reach 750,000 barrels a day, making Guyana Latin America’s fourth-largest oil producer and perhaps the world’s largest per capita oil power, generating a barrel per person per day. Oil revenues are expected to climb from zero to almost USD 631m by 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund. Income per capita will more than double by next year, topping USD 10,000. Overall, its economy is projected to grow by 86% next year — 14 times China’s projected growth rate."

The possibility of large oil finds in an obscure, tiny country was always bound to attract attention. It also attracted the Lundins and a raft of other operators who wanted to get in on the opportunity.

The Lundin Group is present in Guyana through its stake in Toronto-listed Africa Oil (ISIN CA00829Q1019), which in turn has a stake in London-listed ECO Atlantic Oil & Gas (ISIN CA27887W1005). These two firms are among the smaller operators in the space, and ECO has been a fairly focussed play on the Guyana opportunity.

Following the large-scale discoveries of recent years, there are now at least half a dozen publicly listed companies invested in Guyana. A medium-sized operator with Guyana activities is London-listed Tullow Oil (ISIN GB0001500809). Then there is NYSE-listed Exxon Mobil (ISIN US30231G1022), where the Guyana activities make up a large enough proportion of the overall portfolio to regularly get mentioned in investor material. The NYSE-listed Hess Corporation (ISIN US42809H1077) is invested in a Guyana joint-venture alongside Exxon Mobil, as is the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (ISIN HK0883013259). Another NYSE-listed company that has drilling rights in Guyana is Occidental Petroleum (ISIN US6745991058), which ended up with a license following its acquisition of Anadarko Petroleum. No doubt, there are others that I've missed. Also, there are now oil-related plays for the other Guianas. Total (ISIN FR0000120271) and Apache (ISIN US0374111054) have been drilling in neighbouring Suriname.

What do most of these companies have in common?

In recent times, their share prices have been on a roller-coaster ride – and mostly, they have fallen in value.

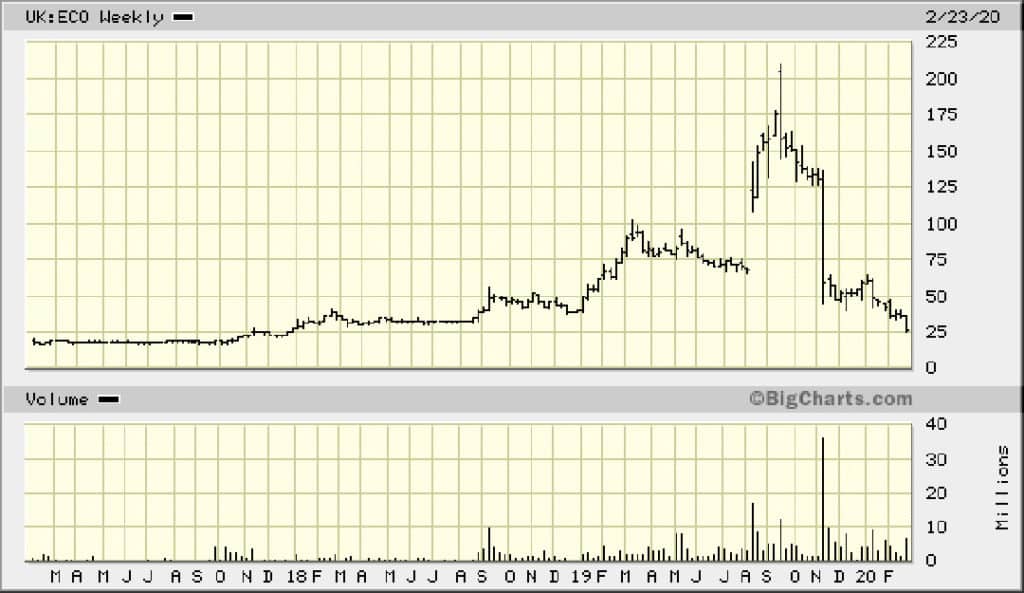

E.g., ECO Atlantic Oil & Gas rose by a factor of ten over the three-year period from mid-2017 to mid-2019, only to collapse back to its starting point over the past six months because of disappointing drilling results.

ECO shareholders at first made ten times their money – and then the market took it all back.

Will some of these shares ever recover, and is there money to be made off the Guyana opportunity? If he were still alive, Adolf Lundin may have reminded investors of his favourite motto: "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." The founder of the Lundin group had a lifelong knack for topping up his holdings during tough times. Provided, of course, the data backed up his belief that a turnaround was going to come. E.g., his investments in Russia got absolutely clobbered during Russia's 1998 debt default. Nine years later, Russia was back on top of things and the Lundin holdings had risen to be worth billions of dollars.

In the world of investing in high-risk, exotic countries and ventures, wild fluctuations and extended downward movements are par for the course. As Lundin's biography noted:

"Bo Hjelt, who remained a partner in the Austro International Investment Corporation until its liquidation at the beginning of 2002, recalled the ups and downs of the early days. 'It was always nerve-wrecking to read a compilation of Austro's actual net asset value. It was worse than riding a roller coaster."

I don't hold a fixed view on the Guyana investment prospects – at least not right now. There is also the question whether Guyana offers investment opportunities outside of the oil sector. After all, even glitzy Doha in Qatar once was nothing but a stretch of sand with impoverished tribes. Who knows?

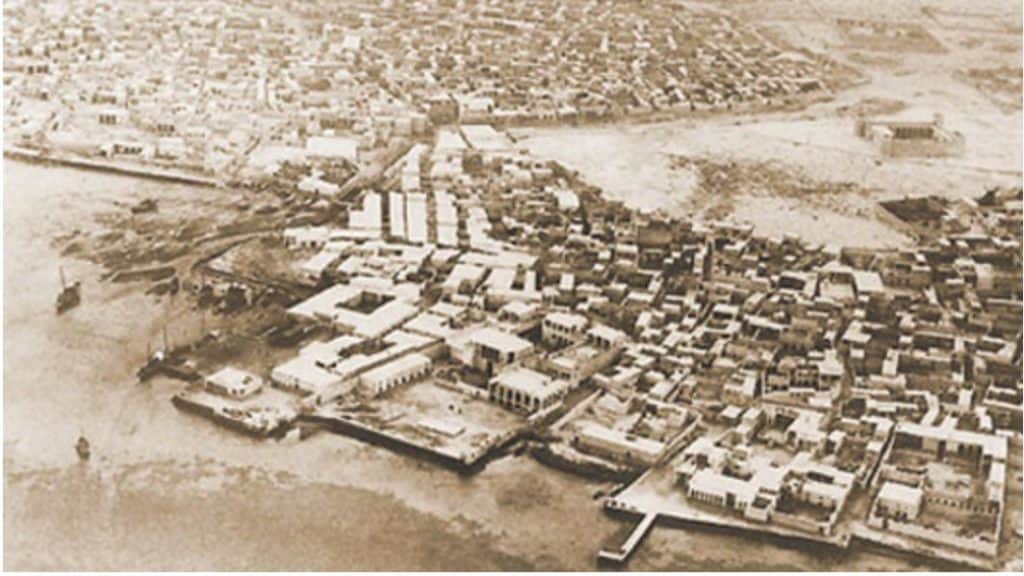

Doha before the gas-money started flowing.

What's guaranteed, though, is that there will always be companies and entrepreneurs that chase the dream of striking it big – and doing so fast! Undervalued-Shares.com will continue to sift through such opportunities on behalf of its readers. Some of these crisis-ridden assets will recover, and some obscure parts of the world will throw off handsome profits for those who have the necessary information (and stomach) for making ultra-contrarian bets on assets that are trading for a tiny fraction of their potential.

How can private investors find such opportunities, and how can they best separate the wheat from the chaff?

It's a question that I will look at in more detail next week, in part 2 of this miniseries about investing in extreme opportunities. I borrowed the title of this column from an out-of-print, hard-to-find book of the same name, and I have a lot more stories of this kind coming your way. Obviously, there is also the odd story on my radar that may soon be ripe for picking up assets for those proverbial pennies on the dollar. With this in mind – and assuming we'll all live to see the other side of the coronavirus crisis – stay tuned for more!

Blog series: Riches among ruins

There's more to "Riches among ruins" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year