Last week's dispatch described the incredible investment success of Adolf Lundin, the late Swedish billionaire. Lundin had made his fortune by investing "where no one else wants to operate because they consider the risks too great." He once saw an investment increase in value by about 500 times over 20 years, and that was just one of his many coups.

In the early 2000s, I researched an investment that would probably have been very much to Lundin's liking. At its peak, the stock price went up 50 times in less than two years. Few captured the ride from early on, though, because the company in question operated in a country that investors were afraid to invest in.

I had discovered the publicly listed company that was likely to be "first in line" once the isolated, war-torn Iraq was to re-open its oil sector to foreign investors.

The key to this investment was a combination of an extremely low stock price and a potentially insanely profitable business. It was clear to me that as soon as there was even a vague promise of the company getting into Iraq to build an oil operation, the stock price would soar on the back of mere anticipation.

At the time, Iraq was estimated to have the world's largest untapped oil reserves. It was also widely known that oil production in Iraq was going to be almost as cheap as in Saudi Arabia because the country's oil reserves occured at a relatively low depth. Just as in Saudi Arabia, you could stick a shovel into the sand in some areas and the oil would come up right away. Cheap production costs equal high profit margins from selling the oil. The prospect of exploiting these resources promised riches for those who had a license and the operation to do it.

"The Eternal Flame of Baba Gurgur": A stretch of sand in an Iraqi oil field near Kirkuk is said to have been burning for 4,000 years. Oil is seeping to the surface in a natural process. Underneath is one of the world's largest known oil fields. Source: World Atlas

The story was verifiable and easy to comprehend. Still, no one wanted to hear about it at the time.

The problem was that I wanted to write about this company BEFORE the Iraq War.

Conventional publishers were too afraid to have me write about it

Obviously, this was a company with outsized risks.

Think back and imagine the following situation.

Saddam Hussein was still in power.

The Iraq War was about to happen. The US government had already lined up troops to invade the country, though no shot had been fired yet. Some augurs predicted the US and its coalition forces could not win, and that it was going to be a Vietnam-style bloodbath for the Americans. In November 2002, The Guardian published a lengthy analysis titled "The Iraqi army is tougher than the US thinks", which warned of a "worst-case scenario for US military planners."

The oil drilling rights held by the company were tentative rather than contractually agreed. While all paperwork with the Iraqi government had been finalised, the Ireland-based company couldn't sign the contracts because this would have been against global UN sanctions. The investment required faith that an eventual post-war government would act in a pragmatic, can-do fashion, and honour the tentative agreements to get foreign investment going without delay.

Given the overall situation, I was always clear about the risk that this investment could be wiped out entirely. Equally, I saw a realistic chance for matters to work out. A back-of-the-envelope calculation showed that in the case of success, the stock could increase in value by more than 300 (!) times. Wouldn't that be worth a punt?

I approached a handful of publishers about the story, and was surprised that no one wanted to give it any editorial space:

- "Too political."

- "Too controversial."

- "War-profiteering."

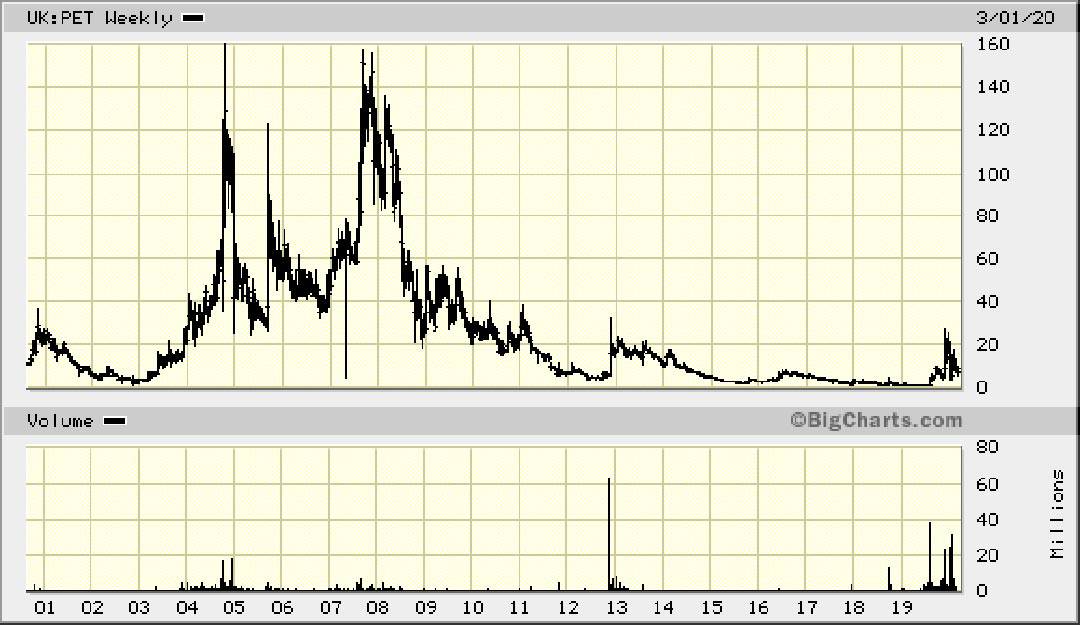

That didn't stop the stock from becoming one of the best performers of the London Stock Exchange at the time. Its price went from GBp 3 to GBp 162 at its peak, a more than 50-fold rise in less than two years. It also became a bit of a media sensation. (FYI: GBp = pence; GBP = pound sterling)

But all that came later. At the time when I wanted to get the story out, corporate publishers were too afraid to be seen doing something that wasn't socially acceptable.

In the end, I did get an article published about it. Gerhard Kurtz, the uber-controversial German newsletter author, slipped my Iraq story into his annual investment report. He sent my report to his readers towards the end of 2002 when the stock was trading at GBp 3.

I am glad that SOMEONE let me write about it because I now have a stack of documents about this investment case. For this article, I checked back on my own writing from days long gone by and realised that there are a whole number of useful lessons to be learned.

Today's issue will look at the following such lessons:

- How to find such opportunities in the first place.

- Which crucial aspects you need to check during your analysis.

- Why private investors are better equipped to exploit such extraordinary situations, than institutional investors with all their limitations and restrictions

Here is a quick-and-dirty instruction manual for researching investments in some of the world's riskiest, off-the-beaten-path locations.

Between 2002 and 2004, Petrel Resources increased in value by over 5,000%.

Finding stocks to match exciting stories

In retrospective, finding this particular opportunity wasn't all that difficult. It was mostly a matter of following world affairs and spending a bit of time on search engines. I did get a bit of an additional edge because I managed to attend a meeting of Iraq oil sector insiders in London, but that wasn't a deciding factor.

Everyone knew at the time:

- The US was going to invade Iraq to push through regime change.

- Iraq had some of the world's largest, least-exploited oil reserves.

- Assuming the war was going to end with success for the US-led coalition, it was going to be a political priority to mobilise foreign investment for the Iraqi oil sector.

One could have argued that the US was not going to win the war and that Saddam was going to stay in power (a legitimate concern). That question aside, the situation seemed pretty clear to me.

What's more, it was a situation that was not difficult to find or to learn more about. Has there been ever a shortage of political, economic and financial crises in the world? The Iraq War was a particularly prominent development, but it really only takes reading major newspapers and magazines to find more such situations. If you want to generate ideas along similar lines, you could simply subscribe to The Economist. For all its faults, The Ecomomist has always been pretty good when it comes to featuring crises in out-of-the-way locations.

However, what few people do when reading about countries that are in an extreme crisis, is to check the world's major stock markets for any publicly listed company that is going to benefit from transformative changes. Connecting these dots is where diligent research and a bit of forward-thinking can generate tremendous financial value for yourself

As I never tire of pointing out, there are around 100,000 publicly listed companies in the world. Assuming your broker is able to execute trades on the world's major stock exchanges, you can easily buy and sell shares in at least several tens of thousands of different companies

You'd be surprised how much diversity there is among companies that are listed on a stock exchange. I sometimes challenge people to name ONE industry, technology or theme, and I will dig out at least one publicly listed company that is trying to exploit it. You might not always find a company that is listed on the stock exchange of your home country, but there'll be one listed somewhere – or two, or three. Given that most companies publish their information in English, it's not that difficult to locate them. We live in the greatest era ever for exploiting investment opportunities around the world.

Surprisingly often, you'll find companies that operate in exotic markets but are listed on the London Stock Exchange. More so than any other major stock exchange, London seems to attract super-risky ventures that aim to invest in crisis-torn jurisdictions. I always check the London market first, not the least because London-listed stocks are so easy to trade.

Such was the case with my interest in the Iraqi oil sector, Petrel Resources (ISIN IE0001340177, "PET" on the London Stock Exchange).

The company I managed to find – without doing much more than spending a few minutes using the prevalent Internet search engines of the time – was incorporated under Irish law, listed on the London Stock Exchange, and focussed exclusively on emerging opportunities in the Iraqi oil sector

Finding opportunities such as Petrel Resources does not need to involve placing orders on exotic stock exchanges, nor does analysing them necessarily need to be a daunting task. In my view, you can identify and analyse such opportunities in a matter of a few hours. All you need to do is check the usual set of facts that any good company requires to succeed, and which I'll now outline for you.

It all starts with having the right team

Any venture capitalist will tell you that the success of a company primarily hinges on the quality of the people behind it.

Once you have used the wonders of the Internet to find the right company (or companies), you should check the track record of the people who are in charge

Its directors will have their bios on the company website, and there might be information available elsewhere about their past track record.

More likely than not, there will be major shareholders, either institutions or individuals. Under normal circumstances, you'll be able to find out something about them, too. Were their past investments successful? Do they have expertise in this particular industry or country? What were their motivations for making this particular investment?

In the case of Petrel Resources, I found out that

- David Horgan, the company's chief strategist and major shareholder, had managed to get the second oil license issued by Bolivia after the country opened up for exploration. He also had a verifiable track record for establishing a foothold in Iraq. E.g., in 1999, his private jet was the first Western private jet in eight years to be granted landing permission in Iraq.

- John Teeling, the company's chairman, had single-handedly sparked the revival of the Irish whiskey industry in the 1970s and 1980s. He was one of Ireland's best-known entrepreneurs and investors. Teeling was not without controversy, but that comes with the territory when you disrupt an industry. As the American saying goes: "The more danger, the more honour." (For my German readers: "Viel Feind, viel Ehr.")

- Its largest institutional shareholder was a small companies fund operated under the Gartmore brand and managed by Gervais Williams. British readers will instantly recognise the name, given that Gervais is one of the UK's most successful fund managers for small -and micro-cap companies.

Details aside, having several such names onboard was a strong initial indication that the company's team stood a chance of succeeding.

If such a team is in place, you should continue and check a few essential fundamentals.

3 crucial factors to check about the business

Analysing a business in detail would go beyond what I can describe in a single article. What I can do, though, is point you towards three critical factors that you should check first.

Does the company have a sufficient cash runway? Most likely, the company you are looking at will have plans that are not yet fully funded and which will require more fundraising down the line. Fundraising is best done in stages, and usually takes 12 to 18 months of preparations before the next fundraising round can be done. Is there sufficient gas in the tank to enable the company to operate until it can carry out the next round? It doesn't take a degree in accounting to work out how much cash the company has at its disposal and how long that will fund the existing operation. If in doubt, simply ask the company's investor relations or PR department. (If you want to learn more about fundraising for entrepreneurs, I have written fairly extensively about the subject on my personal blog, where I publish free articles about subjects such as becoming an entrepreneur.)

Is the company a pure-play on the investment theme you are looking to exploit? Put another way, is the company's business focussed on the investment theme or is the relevant activity just a sideline? If it makes up only 10% of the company's overall operations, you might end up being right about your assumptions, but the company's success may not show up in the share price because it's too small a part of the overall business to move the needle. The closer the company is to a pure-play, the better. Petrel Resources was a perfect case in that regard as it only pursued activities in Iraq. You'd want an entrepreneurial venture to be 100% focussed on the theme that interests you.

Does the overall constitution of the company and its plans pass a sense check once you have read all publicly available material? I have been a lifelong generalist, and I believe that common sense enables you to assess most business opportunities. If all the previous checks were positive, it'll be worth spending the time to read up anything and everything you can find about the company, the surrounding circumstances, and the overall subject matter at hand. Once you have done that, does it still strike you as a good idea? There will be exceptions, but most of the time, you'll be able to tell. You'll simply have a sense for it.

If the potential opportunity you are looking at still strikes you as promising, then it'll be time to assess what I call its suitability for the hype machine.

What's the hype machine?

An ex-girlfriend of mine coined that term, at least as far as me using it is concerned (it was also the name of an early Internet company that went bust in 2005). Back in the days when I was active on Facebook, she called my social media presence "the hype machine".

The girlfriend is gone, but I have kept using the term.

I use it to describe the effect that popular media channels can have on a company's stock price.

When a new investment theme takes off, it usually does so in the following pattern:

- An initial burst of public interest and a soaring stock price, driven primarily by media coverage and expectations about the future.

- Following the initial euphoria, a realisation that building the business will all take a lot longer than anticipated. The stock comes back in price, and there is often huge volatility.

- Eventually, the original assumption comes true, and the stock climbs up again. It usually does so at a slower pace than during the initial hype, but often leads to even loftier heights than during the initial ascent.

There is probably no need to mention that we live in the day and age of social media hype and general media hysteria.

If an investment idea is suitable for gathering media attention, it could very well lead to stunning initial gains.

Such was the case with my Iraq oil story.

A few months after I wrote about it, Oil-Barrel.com started to write about Petrel Resources and its plans. The specialised publication was headed by a former Financial Times journalist, and it had a massive following in British investment circles at the time. (In a strange twist of fate, in 2015 I became CEO of the media company that owned Oil-Barrel.com, and had to lay off that same journalist. Only while researching this Weekly Dispatch did I connect these dots in my mind. It truly is a small world!)

Yet a short while later, the Financial Times started to report about the company. Its first article was headlined: "Petrel pushes for a slice of Iraq’s oil action". It's incredible to think back how fast the situation changed from no one wanting to write about it, to the world media latching on to the story. In the meantime, the US-led coalition army had walked all over Iraq in a matter of weeks, and Saddam Hussein had disappeared into hiding. All of a sudden (but not surprisingly), the story took off.

The hype machine of the time – which were pre-social media days, so mainstream media was key – led to substantial public interest in the company. By the time the FT reported about it, the stock price had already increased to GBp 25. The FT's article then propelled it to GBp 45 in a matter of days. This was already 15 times the price at which the stock had traded when Gerhard Kurtz sent out my article to his followers.

This was also the time when I advised people to take at least some of their profits off the table and keep a small part just to continue riding the story and seeing where it all goes.

In the end, the stock went up to GBp 162. I can't claim to have bought at GBp 3 and to have sold at GBp 162 (nor would I know anyone who did), but I do like to think of Petrel Resources as a model-case story for finding outrageous profits in the most controversial of places. My bank records of that era disappeared in a shredder a long time ago, but I do remember that I made some pretty decent money off my find.

Exploiting media hype vs. waiting for the actual plan to work out

Keep in mind that there is often a vast difference between the stock market expecting a company to succeed, and that company actually succeeding with its plans.

Most of the time, there is, at the very least, a significant time lag between the two. Hardly anything ever works out in a straight line.

In the case of Petrel Resources, impressive initial advances to build a new oil company were scuppered by never-ending political issues. The company did manage to get a contract for upgrading its 10,000 sq km (3,861 sq mi) oil fields, but Iraq never passed the new necessary investment laws to make large amounts of foreign cash flow into its oil sector.

The entire story did continue to generate interest, and the stock reached near-record levels on several occasions between 2005 and 2009. However, investors' confidence and patience were exhausted eventually, and indisputably adverse developments killed off the Iraq oil story. As the company's website put it: "Bureaucratic interference … forced Petrel to sell out (its Iraq licenses) in 2010."

Amazingly, the stock continued to trade between GBp 20 and GBp 30 for a while even after the plans for Iraq had collapsed. In the meantime, Petrel Resources had decided to pursue speculative oil and gas ventures in Ireland and Ghana. The dream of striking it big was kept alive, and the company did always keep an eye on potential developments in Iraq. The initial plan, though, was not going to come to fruition.

15 years later, the company still hasn't produced any oil or gas - not in Iraq, nor anywhere else.

By mid-2017, its stock price had fallen back to the GBp 3 at which I had first discovered it. In the space of 15 years, it came full circle.

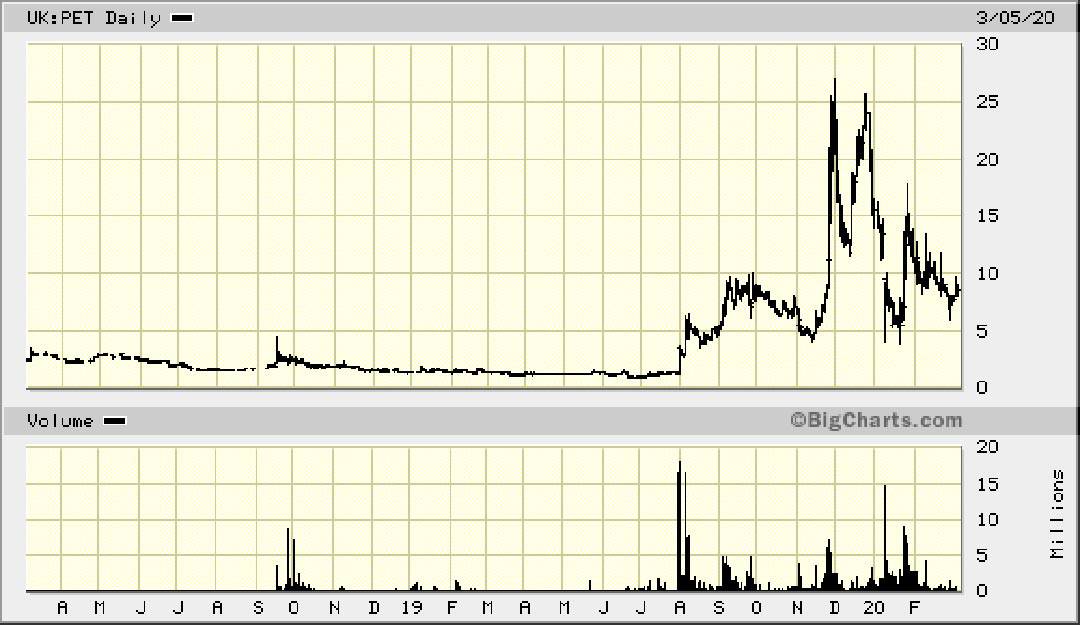

By spring 2019, it was trading for less than GBp 1. Even during the lead-up to the Iraq War had the stock never traded at such a low level.

Then, something peculiar happened.

Starting in July 2019, new interest propelled the stock price to GBp 23 in a matter of just four months. That was a 2,200% increase compared to the low point of the stock. You couldn't have bought major amounts of stock at its record-low price, but you certainly could have deployed GBP 5,000 or GBP 10,000. The subsequent rally could have made anyone some decent money. Turning GBP 5,000 into GBP 115,000 (or even GBP 1,000 into GBP 23,000) is not to be sniffed at, no matter what size portfolio you manage.

As often in these cases, the company came around for another round of speculation and hope. Few such companies truly die and vanish. Instead, they usually simply go dormant for a while before the next generation of hopeful entrepreneurs and investors have another go at it. Entrepreneurial dreams tend to have seven lives.

The stock of Petrel Resources has recently seen another run-up.

The Iraq oil story is back – again!

In July 2019, Petrel announced that it had appointed Riadh Mahmoud Hameed to its board of directors. Riadh was well-known to the company's investors, having worked as Petrel's project co-ordinator in Iraq for six years.

As the company's annual report described it:

"Activities are normalising in Iraq. There are many oil projects in Iraq which need to be developed. Petrel will be making a case to be part of the development. … Interest is reviving in Iraq. We now have the people to seek out operations on the ground."

Its corporate website still contains what lies at the core of the speculation:

"Iraq officially has 153 billion barrels of proven reserves; there are many undrilled prospective leads and prospects, representing about 300 billion barrels of possible reserves. … Operating costs are one of the lowest in the world at under USD 4 per barrel. Iraq is largely unexplored for deep and unorthodox plays."

Still a terrible region, still a terrific investment opportunity (if you can stomach the risks).

And in September 2019 the company stated:

"The security situation has dramatically improved since 2018. Iraq remains exempt from OPEC quotas, and Iraqi oil output has reached 4.7 million barrels of oil daily. The next Iraqi bidding round (for exploration of blocks with gas potential) is expected during 2020. The model contract is expected to be an updated version of the Iraqi hybrid exploration and development contract, incorporating aspects of service contract and production sharing. These terms are more attractive for international explorers than in prior bid rounds."

During the past few months, Petrel Resources stock has seen tremendous trading volume and a revival of sorts. It also got a fresh injection of cash from investors.

Which is another lesson learned that can be useful in your endeavours. You don't necessarily need to find entirely new stories and themes. Instead, you can make decent money by checking back on stories that didn't succeed at first, but which have the potential to come back for another wave of investor interest.

Petrel Resources did just that, and other stocks out there will do the same in the foreseeable future. The world's stock market is littered with dormant zombie companies, some of which will see a revival and produce incredible gains for investors.

You won't be surprised to hear that I have a few such cases on my radar. Seeing how I could have picked up Petrel Resources at just one pence certainly whetted my own appetite again. Count on me for eventually digging up one or the other such idea at the right time.

Blog series: Riches among ruins

There's more to "Riches among ruins" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year