Image by Zhao Zheming / Shutterstock.com

Activist investing may well be the premier league of fund management.

Buying large stakes in companies and shaking up their management has produced stunning returns and world-renowned fund management celebrities:

- Carl Icahn, who has a 40-year track record of activist investing, is America's 26th-richest man and the world's fifth-richest hedge fund manager. At age 84, Icahn is still at it, as his recent transaction in Occidental Petroleum (ISIN US6745991058) proved. He is probably the world's no. 1 poster child for shareholder activism.

- Dan Loeb of Third Point has popularised activist investing based on writing scathing, public letters to management teams he disagrees with. Bloomberg called him a "rabble-rouser" in an epic profile article (which, interestingly, was recently scrubbed off the web).

- Chris Hohn of The Children's Investment Fund became Britain's answer to American activist investing. He produced stunning results for his investors (see my previous article about his involvement at Getlink), turned himself into a billionaire, and produced billions of charitable donations along the way.

For a long time, activist investing used to be the domain of American and British fund managers. In recent years, it has become more of a thing in Europe, too.

Why was Europe behind so much, what has changed recently, and how can you make some money off it all?

Here is the background information you need as historical context, and an analysis of an instructive activist situation currently brewing in Belgium.

Germany as the lead example of why Europe lagged behind

The concept of large investors quarrelling with corporate boards took hold of the American and British stock market in the early 1980s. It's taken a few more decades for it to arrive in Continental Europe. It's finally happening, though.

In August 2017, The Economist wrote:

"Such tussles used to be relatively rare in Europe. But shareholder activism is on the rise, with restive investors demanding corporate overhauls."

Germany, the largest economy in Continental Europe, makes for an interesting case study. As the annual review of Activist Insight mentions in its 2017 edition: "Germany has long been a laggard in the space of shareholder activism due to both legal and cultural challenges."

That's a very diplomatic way of putting it. Legal scholars with a knack for history will point to a much juicier origin of the problem.

The reason why it had long been tremendously tricky to hold German boards to account for underperformance, dates back to the legal system established by the Nazis. Germany's first extensive corporate law was written in 1937, and the new legal code's approach to managing corporations was based on the "Fuehrer principle" (Führerprinzip).

Anyone who wants to study the relevant history should get a copy of "Aktienrecht im Wandel" (roughly: "Corporate Law during changing times"), the definitive two-volume book covering the last 200 years of German commercial law.

The Nazis specifically wanted to create a corporate law designed to:

- Fend off "the operational and economic damage caused by anonymous, powerful capitalists".

- Enable directors to manage companies "for the benefit of the enterprise, the people, and the Reich".

- "Push back the power of the shareholders meeting".

The Nazis lost the war, but the legal system underpinning German corporations and much of the underlying culture remained in place. It was only in 1965 that Germany's corporate law was significantly reformed, primarily because of one man's outrageously broad influence over leading German corporations: Hermann Josef Abs, who had been a director of Deutsche Bank since 1938.

During the years of Germany's so-called economic miracle, Abs had created an impenetrable network of cross-holdings among companies and directorship positions doled out among a small clique of leading figures. This powerful elite of directors shielded each other from accountability; even investors with large-scale financial firepower found many German companies an impenetrable fortress. Germany's government had no other choice but to (finally) act. The Lex Abs, as the legal reform was called in a rare legislative reference to one specific individual, did away with at least some of the corporate law's problematic aspects.

Changing the legal code was one thing, changing the underlying culture another. So powerful and deeply-rooted was Abs & Co.'s system that I came across its influence on the German stock market as recently as the late 1990s. Germany's large, publicly listed corporations used to be a closed shop, summarised by the expression "Deutschland AG" in foreign media.

It was only during the early 2000s that shareholder activism slowly started to become a more regular occurrence in Germany and across Continental Europe. Factors such as a generational change on boards, further legislative reforms, and a large number of newly listed companies managed by internationally trained directors and entrepreneurs led to an increased prevalence of the activist approach.

Once you join the dots from a 30,000 foot perspective and with the benefit of hindsight, it's incredible how long it takes to soften up a well-entrenched system. Quite literally, it required the generation who had created the system to die.

Abs' 1994 obituary from Britain's Independent makes for fascinating reading.

How activist investing arrived in Continental Europe

Germany makes for a tangible story, but the same problem existed in one form or another in most other major Continental European economies.

Guy Wyser-Pratt is a useful case study for understanding how, since the early 2000s, activist investing has been on the rise across Continental Europe. The American fund manager and activist was born in Vichy, France, in 1940, and arrived in the US at age seven. With his European background and successful hedge fund operation built and based out of New York, he was ideally suited to bring activist investing to Europe.

In 1999, Wyser-Pratt made waves in Germany when he intervened in the hostile takeover battle between Britain's Vodafone and Germany's Mannesmann. As a 2019 scientific analysis of Wyser-Pratt's success and influence put it, "he was one of the first foreign investors who brought the investment strategy of shareholder activism to corporate Germany."

His high-profile involvement in what was then the "mother of all hostile takeovers" (as far as Germany was concerned) was only the beginning.

Between 2001 and 2011, Wyser-Pratt decided to take on an impressive number of high-profile family companies in Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland. These were some of the most closed-off European countries as far as investor influence was concerned. You may remember the occasional flurry of horrified media reporting, which almost always included Wyser-Pratt's infamous quote that underperforming boards should "wake up and smell the napalm".

The former US Marine Corps commander never minced words. In a 1999 article by Forbes, he was quoted: "Europe's business elite run companies for themselves. They want absolute power. We're going to be a catalyst for change, and make a lot of money in the process."

And money he made. According to the scientific study of his activism, his investments in Europe outperformed the market by 6.2% over a 19-month window. Wyser-Pratt wasn't actually all that successful in achieving his demands. Merely shaking the cage and causing a stir in the media were enough to make his investments in undervalued companies become a bit less undervalued. The 1999 Forbes article stated that investors in his fund enjoyed a 29.5% annual return, which would have been an excellent result.

Wyser-Pratt has scaled back his activist work in recent years, but he deserves credit for having had significant influence in bringing activist investing to Continental Europe.

In his wake followed a slew of well-funded American and British hedge funds who took on sleepy companies across Western Europe. Things are quite different now. Elliott Advisors, the New York-based hedge fund and world's largest activist investor, has already pursued a whole number of cases across Europe. Activist investing has become a part of the European landscape.

There are now even a number of locally grown European activist investors.

One of them, who has been particularly successful, is the subject of today's Weekly Dispatch.

This August 2017 article by The Economist provides a good overview.

A German activist operating from Luxembourg

When it comes to investing and fund management, nothing speaks louder than performance figures.

The activist fund investigated by today's Weekly Dispatch has earned investors a return of 23.7% p.a. since its inception in late 2015. During the same period, its benchmark has produced a loss of 1.4% p.a. During the first quarter of 2020, the fund outperformed the market by losing just 8%, compared to a 26% loss of its benchmark - outstanding results by anyone's measure.

These performance figures belong to the Active Ownership Fund, which is managed by the Active Ownership Corporation (AOC) in Luxembourg. The fund isn't publicly listed, and it reportedly requires a multi-million minimum investment to become a member of the club.

AOC was set up by Klaus Röhrig, a German national who previously managed the Germany-related investments of Elliott Advisors. However, instead of calling themselves "activist", AOC has chosen the more polite European term "active owner".

The fund's website states:

"AOC is an independent, partner-managed investment company acquiring significant minority stakes in publicly listed, undervalued small- and mid-size companies in German speaking countries and Scandinavia. AOC follows an active ownership approach and fosters value creation through operational, strategic and structural improvements.

For us, active ownership means that we act as the company’s partner and support it long-term. Together with management, we define value-enhancing strategies and measures and are ready to support their implementation as supervisory board members and advisors. We have access to a dedicated pool of experienced industry experts, that help us to identify and realize strategic and operational improvement potential."

Semantics aside, the result is the same.

AOC buys significant stakes in undervalued companies and finds a way to directly influence the fate of the company.

The wording may be different, but the essence of the approach is identical. What's more, the results so far speak for themselves.

Look no further than Agfa-Gevaert, the venerable Belgium company listed on the Euronext exchange in Brussels. Until recently a sleepy company that investors had forgotten about, it's now at the centre of "active ownership" as propagated by AOC.

Why the market had neglected Agfa-Gevaert for decades

The company's name is likely to make you think of photographic films. Indeed, the company created by Lieven Gevaert was a pioneer in photographic papers, film for photography and cinematography, and X-ray panels. The roots of that half of the company's name go back to 1894.

Agfa, in turn, was found in Germany in 1867. The company produced colour dye, which involved the chemical component aniline. Agfa stood for Aktiengesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation, literally "Public Company for Manufacturing Aniline".

Both companies went through a turbulent history of their own, which ended with a merger in 1964. The combined entity, registered in Belgium's Mortsel outside Antwerp, became Agfa-Gevaert. It continued to make headlines with products that improved the lives of millions and kept the widespread appeal of its famous brand name alive. For instance, in 1971, it became the first European company to produce a "xerographic copier".

The historical context may seem quaint, but it's very relevant for the investment angle of Agfa-Gevaert today.

Over the decades, Agfa-Gevaert has gradually turned into the kind of company that many observers from the more dynamic economies of Asia and North America would describe as typical European:

- Venerable history.

- Globally recognised brand name.

- Some remaining strengths in the core business divisions.

- Lacklustre growth.

- Little (if any) investor interest in the company.

- No dominant shareholder.

- A caste of risk-averse directors keen on securing their privileges.

If this didn't sound like an appealing mix to attract investors, it's because it wasn't.

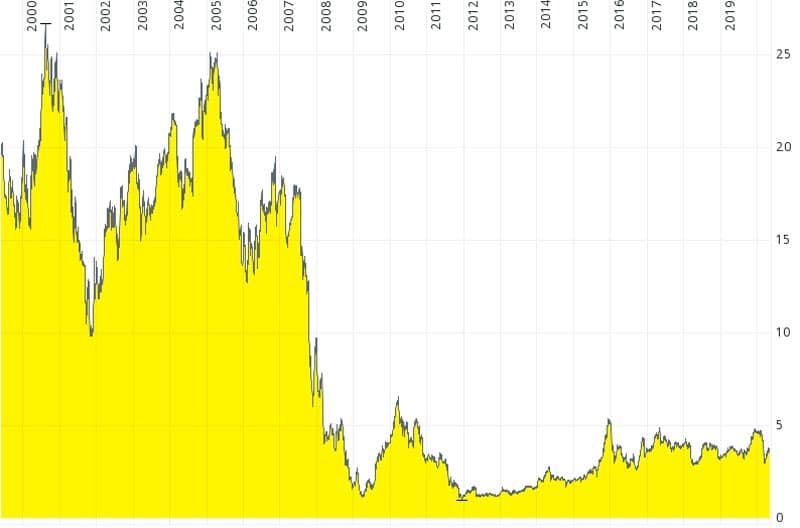

Since 2000, Agfa-Gevaert shareholders have experienced no joy. Following an initial few years of moving sideways, the stock plummeted during the Great Financial Crisis and never recovered.

EUR 1.00 invested in the company in 2000 would have left you with EUR 0.20 until recently. The same amount invested in the Dow Jones Index would have yielded EUR 1.50, or EUR 2.50 with Nasdaq shares.

No joy for Agfa-Gevaert investors – until AOC took action.

Not only did Agfa-Gevaert lack a growth story, but it was also heaving under an outsized EUR 1bn in pension liabilities (compared to a market cap of just EUR 650m). The company had quite literally become the embodiment of what ageing, slow-growing Continental Europe has become known for in the eyes of so many.

Still, the company was not without attractions.

What was left of Agfa-Gevaert was a hotchpotch of businesses:

- Offset solutions (printing services).

- Digital print and chemicals (printers and printer ink).

- Radiology solutions (imaging technology to diagnose disease).

- Healthcare IT (software for hospitals).

Shareholders always knew that all of these businesses enjoyed a solid market position in their respective fields, and the group's revenue of EUR 2.2bn made it an impressive-size operation. However, the group's reporting was opaque, and the mixture of businesses from different industries made no sense in the eye of investors. The investor community largely ignored Agfa-Gevaert.

Few knew just to what degree the healthcare IT division packed a punch. It was the #1 market leader for hospital software in Germany. Because of its strong market position, a hyper-successful German software company, CompuGroup Medical (ISIN DE0005437305), had already attempted a takeover of Agfa-Gevaert in 2016. Led by a self-made entrepreneur, CompuGroup's stock price had increased by well over 100 times since the mid-1990s. Despite the CompuGroup's stellar reputation and strong balance sheet, the bid approach failed. Agfa-Gevaert's management was too entrenched and didn't want to play ball.

It's reasonable to speculate that AOC buying a significant stake in Agfa-Gevaert was the result of the little-known healthcare IT division and the dismissive treatment of CompuGroup's potential bid.

The healthcare IT division was little-known but proved all the more valuable (image: JHVEPhoto / Shutterstock.com).

Active Ownership meets sleepy Belgian company

In 2018, AOC surfaced with a 13.4% stake in Agfa-Gevaert. All of a sudden, the German active ownership vehicle had become the company's single largest shareholder.

Because of its lack of a dominant shareholder, AOC managed to lift its founder, Klaus Röhrig, onto the board of the company without too much ado. It didn't take long before he became chairman.

The Belgian newspaper De Standaard reported in May 2019 that Röhrig didn't want to come across as an activist:

"Klaus Röhrig has done his utmost over the past few months to keep quiet about his intentions. "AOC has great respect for Agfa’s history and the transformation of the past few years. As a reference shareholder, we believe in the long-term value potential", was about the only thing he wanted to say so far about his entry into Agfa."

It would have taken a degree of naivety to believe that AOC wasn't going to push for significant changes. Three years earlier, Röhrig had shaken up Stada Arzneimittel, the German pharmaceutical specialist for generic and OTC drugs. AOC purchased a 7% stake, fought a 14-hour battle at a shareholders meeting to have the chairman removed, and subsequently replaced the CEO and the CFO. By restrained German standards, AOC's campaign at Stada was akin to a blood bath (with aerial support from Guy Wyser-Pratt, who held 2%). The entire company was subsequently sold in a bidding war, and the share price tripled in just a few months, earning investors of AOC's fund a reported EUR 200m. The case did qualify as activist investing in every sense, including a variety of nasty public tussles and legal skirmishes. Call it active ownership or activist investing – it's all the same but dressed up to appeal to the more fragile Continental European mindset.

Unsurprisingly, significant changes started to take place at Agfa-Gevaert, too. In May 2019, the company announced that it was going to sell substantial parts of the healthcare IT division. Shareholders were left somewhat in the dark about the exact extent of the business put up for sale, which is why, at the time, not many observers paid much attention to it. Expectations at the time were that Agfa-Gevaert was going to pocket around EUR 500m, which would have been about two times annual revenues.

In early 2020, Agfa-Gevaert disclosed a deal to sell the relevant parts of the division for no less than EUR 975m – a stunning 3.75 times sales. Not only was the absolute price tag a surprise. It also happened to be almost exactly the amount that Agfa-Gevaert had in outstanding pension liabilities – EUR 1bn. The winning bidder was Dedalus, an Italian software company that had decided to consolidate the European market for healthcare IT by buying up competitors across the map. It had won the backing of a French financial investor, Ardian, which gave the Italians ample financial firepower. CompuGroup had also entered the bidding process but lost yet again.

All of a sudden, shareholders had the prospect of the pension issue taken care of altogether. Other possibilities beckoned, too. After all, Agfa-Gevaert has no short-term obligation to pay off these pension liabilities.

By now, it's already clear that Agfa-Gevaert has become a different investment proposition altogether. Key questions going forward are:

- How will the cash from the sale be used?

- What's the value of the remaining divisions?

- What are the likely next steps to revamp the company further?

AOC remains invested and is unlikely to exit the investment before other structural changes have been implemented. The stake is illiquid, the job is only half-done, and there is probably more value to be extracted from the company.

AOC reportedly increased its stake in Agfa-Gevaert during the sell-off in March. Which begs the question, is there still money to be made if you invest now?

My estimate how Agfa-Gevaert will use the cash

The sales process of any large company inevitably involves information leaks.

Even though the sale of its healthcare division was only announced in early 2020, Agfa-Gevaert stock had already started to rise from August 2019 onwards. Within five months, it had risen from EUR 3.30 to EUR 4.90. A back-of-the-envelope valuation of the remaining businesses yields that Agfa-Gevaert would probably be worth just under EUR 5 per share if every business division was sold off. The market probably anticipated an eventual liquidation of the entire group and payouts to shareholders amounting to somewhere close to that amount. It could also be the sale of a cleaned-up Agfa-Gevaert with just one remaining division, which is essentially the same thing but potentially more tax-efficient for shareholders.

During the coronavirus crash, the stock dropped back to EUR 3. The market undoubtedly feared that the sale of the healthcare IT division might have to be called off. The deal had already been announced, but it was not due to be completed until the second quarter of 2020. M&A transactions do tend to have an opt-out clause of one kind or another, and the global markets have recently seen a few high-profile deals collapse.

However, this particular transaction appears unlikely to be called off. According to my contacts in the industry, bidders' interest in the division was so strong that Agfa-Gevaert managed to negotiate a financial guarantee from the financial investor that is backing the winning bidder. It's interesting to note that the stock price of one of the losing bidders, CompuGroup Medical, has just reached another all-time high. Healthcare IT and software for hospitals is not an industry that is suffering under the coronavirus crisis. If you won this bid against several other highly competitive bidders, you are likely to complete the transaction.

(Update 5 May 2020: The company has just announced that the transaction was completed.)

Indeed, the stock price has already recovered somewhat, oscillating between EUR 3.50 and EUR 3.75. It's still significantly below the EUR 4.90 that it was trading at when the deal was announced originally.

Agfa-Gevaert since the healthcare IT division was put up for sale.

What, exactly, does the market expect going forward and is there money to be made?

Shareholders can probably expect a range of measures, which I don't think anyone else in the investor media has properly analysed yet.

In a somewhat peculiar but telling development, Agfa-Gevaert's board recently called not one, but two shareholder meetings. The most recent was scheduled to be held on 29 April 2020, with the sole purpose of authorising the board to buy back as much as 20% of the company's entire share capital. It would be an outrageously large amount under normal circumstances.

The regular annual shareholder meeting is planned for 12 May 2020. I speculate that the company aims to use this date to announce the successful sale of its healthcare IT division.

What is the company going to do with its newfound liquidity?

AOC is quite reserved when it comes to publishing information. While it presented the investment case at the MOI Global conference in November 2019 (a summary is available on the web), (to my knowledge) no clear statements exist about the intended use of the cash pile. However, much can be deduced from standard practices of activist investors and simple logic applied to the overall circumstances.

The authorisation for buying back up to 20% of the share capital gives an initial clue. It's the strongest possible signal just how unlikely it is that Agfa-Gevaert will use the entire cash amount to pay off pension liabilities. By their nature, such pension liabilities are payable over decades. It would not be an effective allocation of funds to pay them all off at once.

It is much more likely that the sales proceeds will be put to use in several ways.

1. "Special dividend"

As far as I was able to ascertain, Agfa-Gevaert should have the option to pay out a tax-free dividend of up to EUR 0.50 per share. Technically speaking, it wouldn't be a dividend, but a so-called "capital return" (that's why it's tax-free).

2. Stock buyback

As per above. The authorisation for 20% of the stock capital is the legal maximum permitted under Belgian corporate law. Nothing would preclude Agfa-Gevaert from authorising yet more share buybacks if it had the funds to do so.

The shareholder meeting that was originally scheduled for 29 April 2020 had to be postponed at the last minute, because it lacked a sufficient number of shareholders to reach quorum. The company had prepared for such a situation, and the same authorisation has now been added to an extraordinary general meeting that is going to take place immediately after the ordinary general meeting on 12 May 2020.

3. Pension liabilities

It would seem wise to reduce the pension liabilities to a more manageable level. By making a one-off payment to cover liabilities, Agfa-Gevaert would demonstrate financial prudence and reduce the size of the problem to a level where it becomes easier to manage going forward. It would also be easier to eventually sell off the company with one (or several) remaining divisions if that was the plan.

4. Building up the radiology division (to prepare for a sale)

There is quite probably a solid case for investing money into the radiology division. The radiology sector has three major players – GE, Philips, and Siemens – as well as many smaller players across the world. Interestingly, Fuji Film recently purchased the radiology division of Hitachi for about USD 1.7bn. Europe features a range of smaller radiology companies, many of which are too small to operate on their own. The market may just be waiting for a cash-rich bidder to emerge and lead a consolidation. Could Agfa-Gevaert become the vehicle that consolidates the market by hovering up the smaller European players before selling out to a global player? I believe there is a good possibility that Agfa-Gevaert will gradually sell off the remaining divisions except for the radiology business, use its capital to grow the radiology business through acquisitions, and as a last step sell the enlarged radiology business. Doing so would enable selling Agfa-Gevaert to a bidder, instead of having to pay liquidation dividends to shareholders – the latter is more likely to run into tax issues.

How could the EUR 975m sales proceeds be split between these different areas?

It's all in the realms of speculation right now, but it could look as follows:

- EUR 400m for reducing the pension liabilities.

- EUR 300m for buying up smaller radiology companies.

- EUR 190m for buying back of up to 35% of the share capital (in two phases).

- EUR 85m for paying a special dividend (tax-free capital return).

You can shift these numbers back and forth. The bottom line is, once the money has been paid to Agfa-Gevaert, it is likely going to be put to good use in more than one way.

What will Röhrig do?

Looking at it from the perspective of AOC, the investment is now almost guaranteed to become a resounding success, though it does require additional work and more time.

The remaining divisions need to be dealt with somehow, with radiology as the most significant case. To achieve another successful sale, Agfa-Gevaert probably first needs to become the industry's consolidator in Europe. Later, it can sell out to private equity or to one of the global players. If it sold now, it wouldn't achieve an attractive price.

At the same time, a fund like AOC will be keen to avoid any unnecessary tied-up capital, and also see Agfa-Gevaert stock trade at a higher price as it'll prop up its own performance. Returning capital to shareholders and buying back massive amounts of stock can deal with both issues. It wouldn't surprise me if, by way of paying a special dividend and instituting massive share buybacks, the stock price of Agfa-Gevaert was soon manoeuvred back to somewhere nearer to EUR 5. It would merely reflect the expected liquidation value of the company, and any potential gain from consolidating the European market for radiology companies would be the cream on top. Anyone who bought in today could probably earn about 35%, over a period of perhaps six to 24 months. The downside appears to be rather limited, all the more due to the buybacks. If markets experienced another shock and the stock were available at prices nearer to EUR 3 again, the risk/reward ratio would be yet more attractive (refer back to my most recent article about the value of keeping a "shopping list"). It's not a stock that will double in value, but if you are seeking relatively low-risk capital growth by riding on the coat-tails of an experienced activist investor, then this is as good an opportunity as you are likely to find.

Somewhere along the way, a viable solution will have to be found for the other legacy businesses. These are mature businesses in which public equity investors are unlikely to ever take any interest. After 20 years of languishing on the stock market, why would anyone want to keep this group alive?

Quite probably, Agfa-Gevaert will auction them off one after another.

By doing it without undue hurry, the company will ensure the best achievable price is negotiated.

The endgame seems pretty evident to me.

Does the end beckon for the 153-year history of Agfa-Gevaert?

Quite possibly so, but it'll be lucrative for shareholders.

Now that an "active owner" is in charge – dare we say, an "activist" – things have finally started to turn around for the company's long-suffering owners.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year