Metals Exploration’s share price has gone vertical. What’s the key lesson, and which three stocks might be next?

Distressed assets (part 2): António Batista on the European perspective

The prime but hidden location is symbolic of the firm's standing.

As a friend with decades of experience in managing money for ultra-high-net-worth individuals put it: "Caius is one of the best distressed managers. Great returns even in a non-distressed cycle."

Caius Capital, which manages a billion euros, had never given an interview before, though – until now.

Undervalued-Shares.com had an opportunity to sit down with its founder, António Batista, to investigate the distressed asset and high-yield cycle from a European perspective.

António Batista, founder of Caius Capital.

Swen Lorenz: António, what's behind the name "Caius"?

António Batista: The name Caius really goes back to Roman times. Rome is a metaphor for being European-centric, and for the stability and success of the empire. You may remember from Latin courses that Caius was the first name of two very successful Roman emperors, Caius Julius Caesar and Caius Augustus. They, of course, built and extended the Roman empire, and their influence stretches to today in many aspects of European lives.

SL: What was your motivation to set up the firm?

AB: It really goes back to how I grew up. I grew up in Portugal where my father was an engineer in a medium-sized industrial company where he worked at mid-management level. My mother, on the other hand, had her own business. I remember very well that talking to my mother about how her day was when she came back in the evening was actually really exciting. There were good days and bad days, and there were good years and also bad years. But it was always exciting to learn about it and actually exciting to see how much control she had over her own success, at least to some extent. I obviously also enjoyed spending time with my dad, but I was less excited about listening to him and his day-to-day work experiences. My mind was always clear that I would eventually have my own business or at least work in a small setup with friends. It didn't have to have my name over the door. But I was always sure I wanted to work in a small setup.

Of course, I did start my career at Goldman Sachs, which is not exactly a small setup. I enjoyed it a lot, but after five years it was time to move on. I moved to a hedge fund, Och-Ziff, which is now called Sculptor Capital Management. At the time it wasn't a startup anymore, but a small company with maybe a hundred employees, and they had a few billion dollars under management. When I left eleven years later, they had tens of billions under management. It was an amazing success story for the firm, and I was very, very happy to have been a part of that.

Much of what I am right now, I learned at Och-Ziff. It was a great school. They were very well known to hire people who had no clue about investments, very much like myself when I started. They trained people up and gave them a chance to succeed, but also moved them on if they were unsuccessful. I think this is the way to manage people in the investment business. You know quite quickly how good someone is.

It was a great investment experience and a great learning experience. Their risk management was top-notch, as was their culture and team orientation. Given my training in corporate finance and M&A at Goldman Sachs, the firm's focus on fundamentals was something which suited me very well. I spent a very happy eleven years at Och-Ziff, and eventually it was time to move on and go back to the idea of my own setup. I'm very grateful for the experience I had at Och-Ziff. I would never have had the success we've had at Caius for the last seven years without the learning experience at Och-Ziff and all that came with it.

SL: From what little I found about you in the public domain, you were always interested in distressed assets but also in special situations and other parts of the capital structure. How would you describe your investment universe and your strategy?

AB: We categorize ourselves as investors in stressed, distressed and other event-driven situations, and our objective is to generate double-digit returns without using leverage. We do that in an investing universe that basically comprises leveraged capital structures across a range of industries, primarily in Europe. Of course, many of these leveraged capital structures, because they have leverage, will often end up becoming distressed.

SL: What does the term "special situations" mean to you?

AB: We prefer the term "event-driven". "Event" meaning that we invest in situations where we can identify a catalyst that would trigger a re-rating, exit, or P&L event for our investment. We are also patient investors. On the long side, an event can be out maybe 12-24 months. We can invest in something that lasts longer if the company is successful and if more good things happen. But generally, on the long side, at the outset of an investment, we would like to see an event within the next 12-24 months.

However, on the short side, because we have to pay to short a security, it can be quite costly to do so. We therefore like to see the event occur in a shorter timeframe, within 6-12 months for example. Generally, we always like to see an event, we don't just buy something because it's cheap, hoping it will trade differently. So that's the notion of the word "event".

Of course, being an investor in the distressed space, in many cases our events are about companies defaulting, not paying a coupon, or exiting a Chapter 11-like restructuring process. These are the typical events that we are looking for, but there could also be other catalysts.

SL: There is so much talk about the distressed investment cycle and the lack of opportunities in distressed over the last few years. How is it that you generated returns in this environment over the last few years?

AB: I am quite used to hearing this comment, so thanks for bringing it up. I think what many distressed investors focus on is what I would call the traditional distressed cycle, where investment opportunities in cyclical industries, for example retailers and industrial companies, are clearly linked to the economy going up or down.

However, what this often ignores is that there can also be whole sectors of the economy where the distress may or may not be amplified by a weak economy, but its cause of distress is really non-economic. We refer to these as "Investment Themes". Think about European sovereigns going distressed in 2010-2012 because markets were fearful after the Greek experience, or the structured credit bubble bursting in 2008 when people realised they didn't understand what they owned, or going even further back in time, the telco bubble bursting in the early 2000s because of business plans built on fantasies about growth.

More recently, we have been involved in two other investment themes where large sectors have been stressed. This is the energy sector which suffered from energy prices coming down in 2015, and the European banking sector which was hit by a new wave of regulations in 2016. Until that year, it was really expected and common practice for banks to be bailed out by their governments if something happened to them. This new regulation introduced in 2016 – called Basel III or CRD IV – broke that link and made bank bail-ins possible.

Some of these non-traditional distressed sectors have actually not been distressed before, which can often create amazing investment opportunities since there are fewer people who know and understand them. The fancy expression for this is that such sectors offer higher "structural alpha". But on the counter, we need to be quite resourceful when undertaking our research and think carefully about hedging some risks such as in the energy sector. I think as a distressed portfolio manager, one of the key skills is to identify and navigate investments in these non-traditional distressed sectors and find a balance between the opportunity and the risks associated with going off the beaten track.

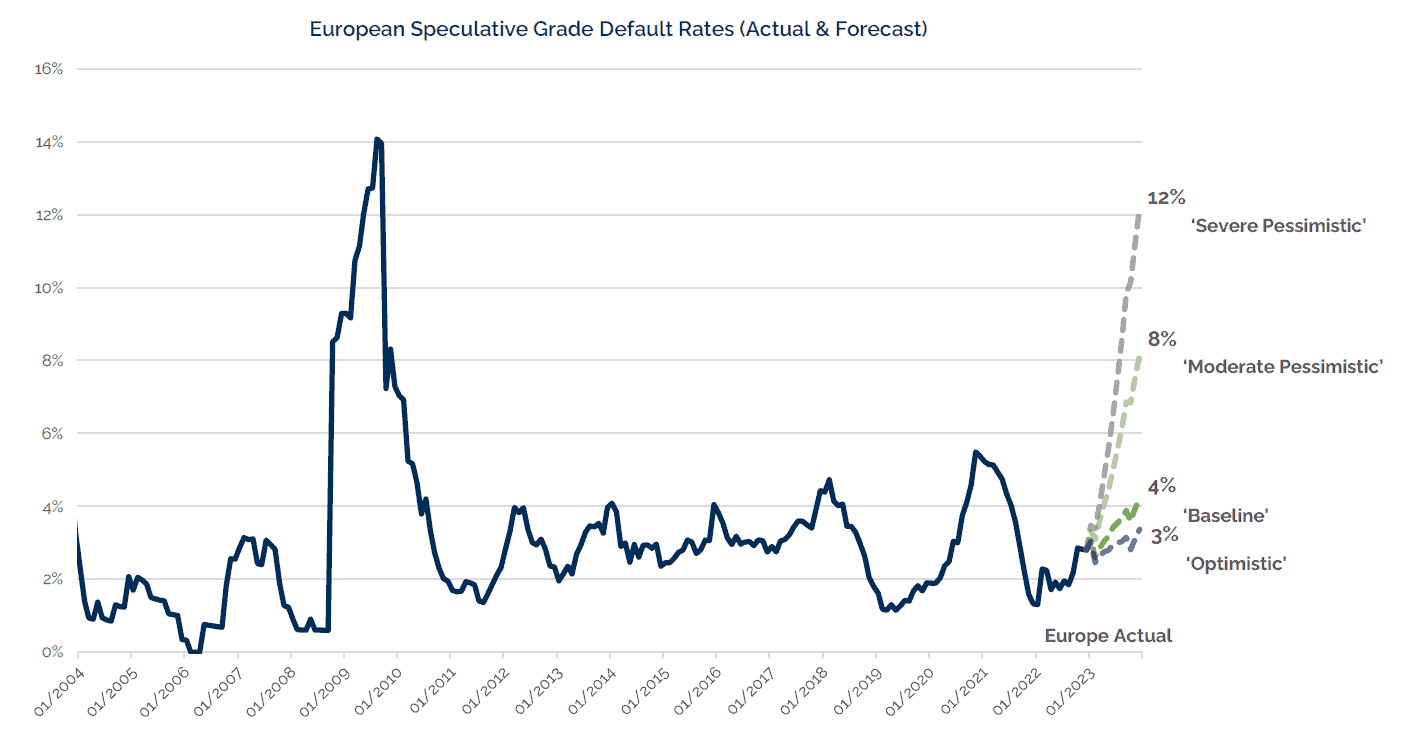

SL: Speaking of defaults, Apollo Global recently published a 150-page research report about the credit market outlook, and their one-sentence summary was that a new default cycle has started. I already touched on this in last week's interview with Rebecca Pacholder of Snowcat Capital, and you may have completely different views about it. I am wondering, what is your view on where we are in the cycle in general, and what may lie ahead in the next one, two, three years?

AB: I think we may all look at slightly different investment opportunities, but I would very much agree with the view that we are currently at the early stages of a new distressed cycle. As I said, when it comes to traditional corporates, the scale of the opportunity set varies over time. It is smaller at the peak of the economic cycle when there is a lot of economic growth, and it is bigger at the bottom of the economic cycle. And we are now clearly entering a period of economic weakness.

That weakness is currently focused on certain sectors. As far as the broad economy is concerned, there is widespread economic weakness, but we have seen few forecasts of a big recession. That said, some sectors are really suffering right now. Energy-intensive industries in Europe in particular – not in the US, but in Europe. Sectors related to discretionary consumption, even grocers, are suffering. Companies where labour is a large part of their cost structures are impacted by unprecedented wage rises. Also, think of businesses which have a lot of leverage and which will suffer from higher financing costs. Real estate is suffering from what looks like an historic change in tenant behaviour. We are clearly at the start of a big, new distressed cycle, and we at Caius Capital are very much looking forward to participating in that.

SL: Given your comments about opportunities in non-traditional sectors and the upcoming new traditional distressed cycle, I am curious if you can you give us some insights into how your portfolio looks?

AB: When we think about distressed investments, it is important to realise that there is a lifecycle to these opportunities. The lifecycle of distressed investment opportunities usually starts with a rating downgrade and operational deterioration, when the market realises that the company's leverage is increasing and may be too high. Eventually, there may be doubts about the company's ability to service its debt, and there is a default and restructuring. This period between a company's operating performance deteriorating to a point where there is a restructuring, and an eventual exit from restructuring, is probably two years, maybe even a bit longer.

However, it is important to realise that this exit from a restructuring is rarely the end of the investment. Even after a restructuring, it usually takes time for a security to no longer be distressed, to experience a re-rating, and to then trade in line with public market valuations of peers. This holds true for both credit instruments and equity. This re-rating can take longer than most people expect and, in my experience, it often takes two to three years after a company has exited from a restructuring. In my view, the entire lifecycle of distressed investments is therefore four to five years, which actually makes distressed investing quite a long-duration investment strategy.

With this in mind, we have a number of investments in the energy and banking sectors which were distressed, they restructured successfully and are no longer distressed right now. They are probably in year one or two after having restructured, and they are now benefitting from a lot of tailwinds that even we didn't even expect to see, such as high and stable energy prices and higher interest rates, so we like them a lot.

On the other hand, it is pretty clear that we have a lot of weakness here in Europe, and we are looking at the unfolding of a new distressed cycle. Within that, we generally don't like to make investments in industries that might still be deteriorating; we like to see a bottoming-out, which may be low, but at least the company should not be deteriorating much further. This means that we are naturally focused right now on many companies that were deeply affected by the pandemic, many even had to stop operating. These companies are now recovering, they may already be back in line with pre-pandemic trends, but they clearly lost two years of their business plan and might have been forced to raise more debt to finance negative operating cash flows. These are often quite good companies in attractive sectors, but now two years post-pandemic, debt maturities are coming up, and many might struggle to repay. Typical sectors include the broad travel space, leisure or elective healthcare where procedures were stopped during the pandemic.

So, our portfolio right now could be thought of as being somewhat bifurcated. To one side, we have investments in formerly distressed companies that have restructured and are now benefitting from a few tailwinds before we eventually exit them in the coming one to two years. On the other side, we have investments in newly distressed businesses in attractive sectors, many affected by the pandemic, where we expect to be active in managing the restructuring.

SL: Do you see this distressed cycle unfolding in a different way in Europe than in the United States?

AB: I have been doing this for more than 20 years now, and no two distressed cycles are the same. There are differences in time, and differences across regions as well.

If we start with regions: yes, they are different. There are lots of commonalities in the US and Europe, such as higher interest costs and higher labour costs, which affect everyone. However, energy costs don't affect companies in different regions equally. Whilst oil is a global commodity, gas is a regional commodity, and gas prices in Europe are way, way higher than they are in the US – by a factor of four, even right now. This means higher costs of electricity, so for example globally-active European companies that are competing against US peers will struggle, and they will suffer. Think about chemicals and industrial companies. Data so far also shows that the US economy in general is doing better than Europe, growth is a bit higher and has been since the pandemic. So, in summary, there is more weakness in Europe, which becomes more obvious when we have a downturn.

Now what is also interesting is the difference in time. We had very different reasons for the distressed cycle in 2008 than we have right now. One of them is that, pre-2008, the financing landscape was actually a bit more cautious. Covenants were tighter, and specifically financial maintenance covenants for example were quite common. This meant that when creditors got involved and there was a default, it was a default because of some covenant breach, not because the company ran out of cash.

Since then, standards for credit documentation have weakened immensely, and covenants have become looser. This means that right now, companies may only default later in their economic deterioration when they are not breaching some financial maintenance covenants but they are actually running out of cash. These companies are usually more distressed than what we would have expected to see back in 2008, and this is certainly one difference that we expect to see in this cycle.

When you are breaching covenants, you may still have cash in your bank account, you may still have liquidity. Going forward, we expect that less to be the case. We expect companies to default because they are running out of cash, which means that there is an urgent need for new money. So, analysing the cash need of the company becomes more and more important. It should always be important, but I think it will become even more important going forward. What is the working capital level? What are the extensions of the payables and of the receivables? Are there any kind of off-balance sheet financing structures the company has used and maybe not fully disclosed?

There has to be more careful analysis of the company's cash need, and the ability of the investor to actually provide new money to the situation will be important. This was less the case back in 2008. The provision of new money, having the necessary fund size to do that, and sizing the position to retain some room to add to this new money will become important considerations going forward.

Maybe one last point, look at different industries. Industries that in 2008 were still growing or which weren't affected are now in the middle of the storm. Think about grocers, which now feel pressure from higher labour costs and higher commodities prices such as agricultural food prices, which they're struggling to pass through. They were not distressed back in 2008. Now, even big, big companies in that sector are distressed.

Also, there are high-quality businesses that were affected by the pandemic and which are still recovering now. They will have lost two years of their business plan, and instead of generating cash they had to use cash and raise more. They can now be distressed. Think of companies in the cinema sector, the travel leisure space, and even the healthcare space. These sectors were typically much less affected back in 2008.

SL: Any other differences between the US and Europe that we should be aware of?

AB: When I talk about US versus Europe, some people point out that the US is so much bigger and more liquid than Europe. That is true, and it is often seen as a negative for Europe. The markets for levered loans and high-yield bonds in the US are probably four times larger than in Europe. But that said, this was much more relevant 20 years ago, when the absolute size of the market was so small. Back then, the European high-yield market was less than 100 billion with a heavy concentration in certain industries, in particular telco and cable. Right now, the loan and bond space in Europe has grown to 1 trillion, and it is much more diversified. Yes, the US may be much bigger at around 4 trillion, but if an investment fund needs that size of a market to find enough opportunities, one may wonder if maybe that fund has become a little bit too large. Europe has enough size, enough liquidity, and enough space for diversification.

That said, there are also those who might point out that the transparency and regime stability of the US are a large advantage: a single jurisdiction, a single language, strong concentration of investment banking activities in one location, an efficient and stable regulatory regime – I think the last big change to the Chapter 11 process was in the early 2000s.

Whether this is a good or a bad thing depends on your vantage point. As a politician focused on the public good, efficient markets are the ultimate goal and you aspire towards that. As investors, yes, we do want some of these elements. For example, we don't want to be exposed to randomness in legal outcomes. But good investors benefit from complexity and an element of market inefficiency, where prices do not always reflect the sum of all available knowledge, and intense research work can lead to successful differentiated views. As investors, I think we should actively look out for more complex and less efficient markets, and Europe, with its multiple languages, jurisdictions, multiple decision-making centres, and improving – but still evolving – restructuring laws is further away from being an efficient market than the US.

SL: All of this sounds like there are fertile hunting grounds for you?

AB: Definitely. There's a lot going on. It is super active, we have increased the size of the team, and we are also raising more money. We think there is a great opportunity in front of us.

SL: On the rare occasion I saw your name in the media, it was always in connection with European companies, such as Bank of Cyprus, UniCredit, and Metro Bank. Would it be right to say you have a European focus but you are globally unconstrained?

AB: We want to be very careful not to be too broad. I am a big believer that we are not the only smart guys in the room. Our competitors are very smart, they are hard working as well, and I respect them a lot. One of my standard sayings that I instil in my colleagues is that we respect our competitors so much that we want to avoid situations where there are too many of them. In my experience, lack of competition is actually a key factor for generating alpha.

Therefore, we actually look out for sectors which are less competitive, and we are super cautious about sectors which we think are very competitive. In some cases, we go into a meeting and see our competitors, and even though it is nice to see your friends, we may leave the room very quickly because it may not be a good situation for us to get involved in.

We want to focus on where we have our core skills and our edge. We know Europe well. This is where we are based and where we all live. We know certain sectors really well, because we have studied them and invested in them for many years. We understand levered capital structures, documentation and inter-creditor dynamics and how to analyse them. We may also sometimes get involved in corporates in emerging markets, which are often very high-quality businesses – otherwise they would not be able to access Western capital markets – and we often see surprisingly little competition, back to my earlier point about structural alpha.

But I really don't like the word "unconstrained" at all, and I would rather say we stick to our knitting. I have been around a little while, and I have had the good fortune to work with excellent, outstanding investment professionals. But I have never met anyone who is good at more than one and a half investment strategies!

SL: Could you talk us through one or two investments that you have done in the past? How did you come across them? How did you analyse them? How did it work out in the end?

AB: One situation we got involved in a few years ago was a company which at the time was called Noreco, they are now called Blue Nord. They were listed on the stock exchange in Norway, and it was an oil and gas production business based in the North Sea. It had run into trouble in 2008 for operational reasons. They had one big oil platform that was becoming physically unstable and had to be removed, in doing so the company incurred huge losses. Then, over a number of years, the company sold off all its assets and in the end, all that remained was a publicly listed entity with zero assets except for a few hundred million euros of tax carry forwards from the losses that the company had suffered in the past and an insurance claim that eventually came to nothing.

Now what was interesting here was that the market didn't really understand what Noreco was able to do with those tax losses. We knew through our analysis that tax losses do not translate from one country to the next. You cannot claim Danish tax losses with HMRC in the UK. Nor do tax losses easily travel across industries, because many countries restrict the use of tax-loss carry forwards between industries. This company basically had little value unless it found an oil exploration and production asset which was producing revenues and profits in Denmark. Now, luckily for us, we knew the energy space really, really well, and we knew there were a few such assets coming up for sale in Denmark over the next 12-24 months. In fact, we later learned that the company made several unsuccessful bids before it finally won the third asset that became available. This was a large minority stake in what is called the DUC, the Danish Underground Consortium, which is by far the biggest oil and gas producer offshore Denmark. The company was transformed from a shell vehicle owning some tax losses to a regular E&P producing asset that benefitted from tax losses and would generate cash. That transaction was the catalyst to the first value step up for us.

But the company didn't just buy any old asset. They actually bought a very complicated asset. The DUC had been producing oil and gas for 40 years. Their 100 wells were operating in a very standard geology in relatively sheltered, benign waters in a well-regulated region. But they had an issue in that their fields had been exploited for such a long time that the platforms had slowly subsided into the seabed. This happens all over the world – every year platforms that weigh up to 50,000 tons subside a few centimetres – and over a 40-year period this adds up. These platforms had eventually subsided about seven metres into the seabed, which meant they had become so unstable that they had to be removed. When these platforms were removed, the field had to close production for almost half of its capacity. You can see that this was an extremely complicated situation and which required a few years of CAPEX to build seven new platforms. There was project risk involved. And then COVID hit as well.

During COVID, the project risks materialised, the CAPEX requirements increased, and there was a delay in the project by about a year. However, we are now post-COVID. The seven new platforms have since been put back onto the field and are being connected. The company says that by December this year they'll start production again. Soon, they should be able to materially increase their production, and we expect this will prove to be the catalyst we have been waiting for to realise value.

SL: Do you have an example from the UK as well?

AB: We had one situation that you may have picked up in the public news at the time, which was West Bromwich Building Society. This was a relatively small bank institution here in the UK with less than ten billion of assets. It was all about retail deposits and then making secured loans in the form of mortgages to households and businesses.

They had an equity-like debt instrument in their cap structure which they had issued many years prior. When the different iterations of bank regulatory changes happened over the last decade – ultimately culminating in Basel III which was implemented in Europe via CRD IV in 2016 – we thought the instrument didn't really comply with the new regulation anymore. What that meant was that the bank had less regulatory capital than it was supposed to have. It had a few choices, such as amending the terms of the instrument, or it could call it and replace it with a new instrument that complied with the new regulation. However, it couldn't just leave it outstanding and do nothing.

We saw that coming. We bought a large position in that instrument at very low prices and benefitted when the bank amended terms and issued new fully complying capital instruments, leading to what was ultimately a successful outcome and a profitable investment for us.

The key here was to have a detailed understanding of bank regulatory capital rules as well as to do detailed research into the documentation of this instrument. The combination of those two allowed us to spot this opportunity.

SL: Can you talk a bit maybe about your team and your idea generation? How do you find these opportunities? And then how do you go about analysing and deciding?

AB: We have a relatively senior, experienced team. I believe that experience is really important in investing, but even more so in distressed than for other strategies because we are dealing with such a big variety of situations. Going back to the distressed life cycle, our investments range from stressed but still performing investments, to full-blown distressed restructurings where intimate knowledge of the process is required, to post-restructuring investments which are no longer distressed but where market and financial analysis are key. We have to be knowledgeable about the industry, the capital structure, the documentation, the regulation, and the restructuring process; but these different components carry different weights according to how distressed an investment is.

I therefore attach a lot of value to experience, and even our most junior analyst has more than seven years of buyside investment experience plus banking experience before that. Across the team, the range goes from seven years to someone who has close to 20 years of buyside experience.

On top of that, I think other skillsets are important. In Europe, we have this multitude of jurisdictions and languages, which creates a lot of complexities and challenges and maybe barriers to entry. As an investor, as I said before, we like to have some of these inefficiencies, and dealing with them makes it easier to develop a bit of an edge. So, we aim to address these language and jurisdictional barriers by having nationals and native speakers of several European countries in our team. We have natives of the UK, France, Sweden, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Ukraine and Russia. Their ability to speak the language is important, but equally important is their natural web of contacts in their respective home country. I think we cover a big part of Europe. I wouldn't say all, but a big part; and for the rest, we have to make do with English.

SL: And how do you find truly new, original ideas?

AB: I see investment research very much as a team effort where people are in different roles, but where we have to come together as a team. Every morning we have a morning meeting which might be as short as 30 minutes on some days, but as long as an hour or two on others. At the meeting we discuss news flow in existing positions, but also new ideas and market positioning.

Idea generation can come from a number of different angles. For example, one of the team might have read an interesting research report, or maybe our trader is informed by one of our sales reps at an investment bank that there is a big seller of company XYZ. Alternatively, they might come from our internal proprietary screening tools or from work we've been doing on a particular industry. They can be sourced internally, through contacts, or through connections in the market. But they are all brought together at a morning meeting, and everyone can chip in. One of my key roles is to decide which ones are worth focusing on.

It's usually pretty obvious which member of the investment team is going to focus on an idea once we've decided we want to do some work on a situation. But choosing which idea(s) to focus on in the first place is less obvious, and it requires quite a lot of judgment because we can't work on everything. One of my key roles as the portfolio manager is to make sure we don't waste precious and limited research time on something that is unlikely to come to a positive conclusion.

SL: We are reading a lot about the distressed opportunity, but this has been talked about for some time. Is it fair to say that it has been delayed? What makes you so certain that it is coming right now?

AB: I think this is a fair comment. I think one of the key drivers for the delayed distressed opportunity set in recent years was government intervention in the form of enormous fiscal largesse and unprecedented monetary easing. It doesn't seem as if either of these is continuing, but as happened in the first half of this year, if they do, opportunities could be delayed again.

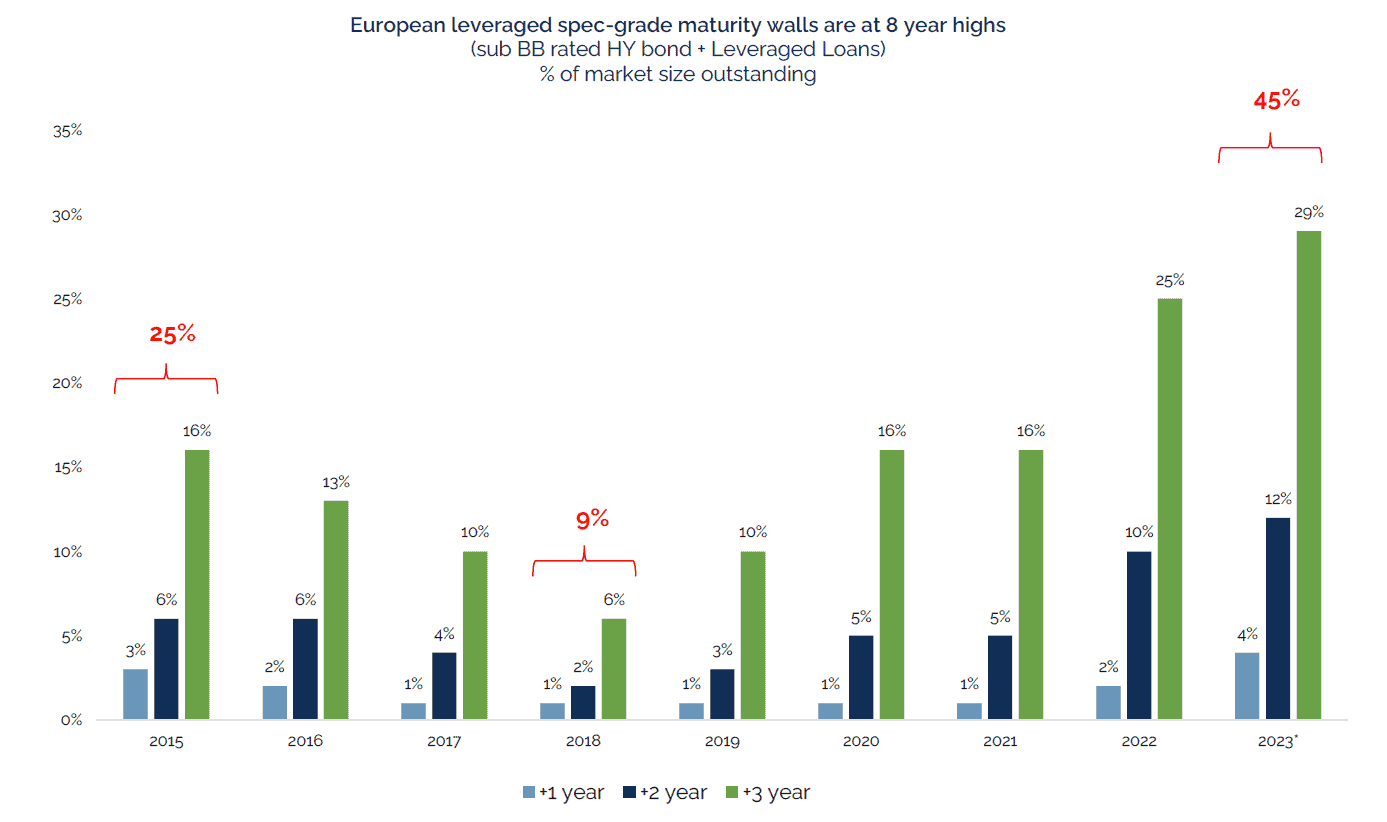

That said, an interesting element that all investors should have on their radar is that of upcoming debt maturities. There is a number that we found, which is that about 45% of the outstanding levered loans and high-yield bonds in Europe are due within the next three years. Again, if you look at the build-up of year one, year two, and year three, it really starts to increase a lot in year two and further in year three. We can then try to overlay the strategic thinking of a company's board, because boards cannot wait until the final day before deciding to start restructuring negotiations. For legal reasons, they have to look forward when they take actions, and they will usually start negotiations 12-18 months before maturity.

So, if you leave everything else aside that is currently creating this distressed opportunity – the high energy prices, high prices of agricultural products, high labour costs and high interest costs – and just look at the maturity profile, it suggests that a big distressed cycle is coming up in the next 12-18 months. That is extremely interesting.

Chart source: Deutsche Bank "2023: Return of the Boom-Bust Cycle", Bloomberg Finance LP, Pitchbook (click on image to enlarge).

SL: What equity sectors do you find interesting right now?

AB: As an equity investor, there are some sectors which are clearly benefitting from the current trends.

Banks are benefitting from higher interest rates, and they are trading on really cheap multiples, both compared to history and the broader market. They are businesses that generate cash, pay dividends, and buy back shares. They were not as exciting a few years ago when interest rates were low, and all the market was looking for was growth.

Energy companies are benefitting from the current energy price environment, whether it is in oil or gas. Some restructured a few years ago, so many investors are not yet comfortable with that, but then maybe this is also what creates the opportunity. In any case, most companies have de-levered a lot and carry little or no debt at all, and they are generating a lot of cash flow which will in all likelihood be used for the benefit of shareholders. I think energy is also interesting to look at on the long side.

SL: On the short side, as an equity investor, what would you stay away from or at least be very cautious about?

AB: My sense is that equity markets are still mispricing – i.e., under-pricing – the interest rate environment, the transition from Quantitative Easing to Quantitative Tightening, and the maturity risks that companies are facing.

There are very high-quality businesses that raised a lot of debt in recent years because it was very cheap to do so. Going forward, those businesses will find it more difficult to refinance. They will not only suffer from the higher price you have to pay for debt, but in many cases the credit markets will not even be willing to extend them the same quantum of debt that they had before. They will only be able to refinance a portion of what they actually have to repay. That's something I'd be cautious about as a public market investor.

SL: What sort of sectors are those in?

AB: Surprisingly, some of these sectors are really stable, and that is why they have so much debt in the first place. Think about the water sector in the UK, or maybe the broader utility space in the UK. Companies across different regulated utility sectors, they're all very highly levered. Yes, they are high-quality. Yes, they are stable businesses. But I am not sure they can refinance their debt. Thames Water just hit the press recently. They have GBP 16bn debt, and many people say they cannot refinance more than two-thirds of that. If true, it means that they have to raise another GBP 5bn in equity from shareholders to fund operations and to fund the de-levering of the business. That is quite material.

Other sectors which are highly levered and which may struggle include telco operators and cable businesses for example.

SL: Do you have any investor heroes or any favourite books that also relate to how you invest which you would recommend?

AB: I do love reading, but it's primarily research about companies and industries rather than books. I read prospectuses and annual reports, and we speak to management teams and investment analysts on the sell side. I read investment research reports from the sell side. In some cases, we might also commission research ourselves. We go to a consultancy, and we ask them to help us with understanding a certain industry, and they provide a report for us. I just love learning about an industry. How does it work, what is the history, where is it going, what are the key trends and the key drivers?

One of the things I love about my job is the opportunity it gives me to learn about a new industry. I may even speak to my wife about that at home in the evening, she often listens patiently and I have the impression she enjoys it as well – I hope I am not totally wrong about this!

SL: Give us an example of the research you commissioned yourself and which proved valuable for you to read.

AB: Like many others, we were surprised by the pandemic and had no clue about how to analyse COVID and the potential chances of finding a vaccine.

Having an edge and sticking to your knitting is very important. But having an edge has two components. One is that I know a lot about the space, and the second is that my competitor doesn't know a lot about the space. Having an edge really results from a combination of the two. When my competitors know very little, then I don't need to be super smart. When they know a lot, I need to work much, much harder.

During the initial phase of the pandemic, nobody had a clue and by doing some good research very early we think we were able to develop a head start. One of the key insights on the economy was that while there was going to be a big trough happening immediately in April, there was likely a very quick recovery from that. We looked at some non-traditional economic KPIs as opposed to financials, such as readily available data for consumption of energy and raw materials, as opposed to backward-looking financial numbers, which indicated that the economic trough was very deep but brief. Looking out further, we followed the process around the development of vaccines from its early days. It became clear to us pretty quickly that it was just a question of time for a vaccine to be found, the key insights being that this was an infection for which most human bodies had a natural defence or were able to develop a natural defence. This was not cancer or AIDS that overruns the natural immune system and for which vaccine research has been unfortunately quite unsuccessful. It was actually much more akin to infections where bodies have developed natural ways of dealing with it. On the most basic level, a vaccination would involve some kind of infection with a small sub-portion of the virus, which would then immunify the body going forward. This was a very basic way of dealing with it, and we knew at the time that there were other, more advanced ways of generating the same effect, involving the mRNA.

Then we followed those vaccine programmes, there were dozens of them, and we could find data across all of them, because data usually has to be filed publicly when certain research is done or when certain trials are run. We knew when trials were planned, we knew when they were started and where they were taking place. We could even estimate when they were going to finish given the infection rates prevalent in the jurisdictions in which they were run.

Therefore, we developed the view early on that it was likely we would see a successful vaccine within a few quarters. We couldn't necessarily say which one would be the most successful, nor how much protection that vaccine would deliver. But we knew the direction of travel, and when such a big dislocation happens, it doesn't really matter whether you're a quarter late or early. If you get the direction of travel right, the results will be pretty good.

This was a good example for an area that we researched deeply, and where we had no prior knowledge. Because few other investors knew about that area either, through some good, detailed research, we were able to develop an edge which then helped us with delivering decent returns that year.

SL: When you are not knee-deep in research reports and analysing the next opportunities, what do you do outside of work, if anything? What are you passionate about?

AB: There are two things I'm passionate about.

One is my job. I think I have a dream job running an investment firm that I set up with some colleagues whom I'm very fortunate to be working with.

But I have a second crush in my life, which is my family. I have a wife of many, many years, we got to know each other 30 years ago. We have three young, healthy children. I love spending time with them. We have a house on the beach in the UK, and one of my favourite things to do is to jump in the water with my children. We as a family believe that, between May and October, there is no excuse not to go swimming every day in the UK, which sometimes may feel like a bit of a challenge, but it is one that we all enjoy.

SL: António, on behalf of my readers, thank you for these amazing insights!

For more information: According to a letter seen by Undervalued-Shares.com, since its inception in October 2016 the Caius Capital International Fund has generated an annualised return of >11.5% net of fees and expenses (through 31 July 2023). Those interested in receiving more information on the work of António and his team should email Jon-Paul Strohacker (Partner & Head of Business Development) on [email protected] (Undervalued-Shares.com does not have an economic relationship with Caius Capital and investors have to make their own decisions.)

Blog series: Distressed assets

There's more to "Distressed assets" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

2 distressed debt investing plays for your radar

Which investments can you use to take advantage of the distressed debt trend?

Check out Gold Reserve Inc. and Burford Capital, if you haven't already.

Both investment cases have further to run, and both are little-followed by the investing public and the mainstream media – and offer all the more exciting opportunities for that very reason!

Undervalued-Shares.com has published some of the most extensive and comprehensible pieces on research available on both these companies.

Now is a good time to take another look.

2 distressed debt investing plays for your radar

Which investments can you use to take advantage of the distressed debt trend?

Check out Gold Reserve Inc. and Burford Capital, if you haven't already.

Both investment cases have further to run, and both are little-followed by the investing public and the mainstream media – and offer all the more exciting opportunities for that very reason!

Undervalued-Shares.com has published some of the most extensive and comprehensible pieces on research available on both these companies.

Now is a good time to take another look.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: