André Kostolany, the late German stock market guru and bestselling book author, landed his two biggest investment coups by buying defaulted bonds. With ancient German and Russian bonds, he made 139 times and 100 times his money, respectively.

Cuba, too, has outstanding defaulted debt, which has long been the subject of ongoing speculation. Defaulted Cuban debt is currently "out", but new developments could soon lead to Cuba's defaulted debt being "in" again.

Defaulted Cuban debt is a rare and exotic asset, but it's open to investment.

In today's Weekly Dispatch, I will tell you the amazing history of 1930s bonds that Hitler defaulted on, czarist Russian bonds that the Soviets defaulted on, and the upcoming opportunity with Cuban bonds.

It's the third and final instalment of my recent writing about more esoteric investments.

Meet André Kostolany, the bond speculator extraordinaire

Kostolany was the closest thing Germany has ever had to a nationally known (and loved) stock market guru. He wrote a widely-read monthly investment column, and his 13 books sold more than 10m copies. "Kosto" died at the age of 93 in 1999, but his books keep getting reprinted, and they have even been translated into Spanish and French (sadly not English).

Kostolany was famous for playing the stock market while travelling between European cities and enjoying life as a bon vivant. Given his fame as a stock market commentator, it is surprising that his two biggest investment coups happened on the back of buying bonds rather than stocks.

To be precise, Kostolany made many times his money by investing in defaulted bonds. He placed bets on countries that had overdue international debt, and which no one expected was ever going to be repaid.

How defaulted bonds come into being

It is entirely within the power of sovereign countries to stop repaying their foreign creditors for any reason (or even no reason at all), but doing so has consequences. If a country defaults on its financial obligations to foreign lenders, it effectively locks itself out of international capital markets. Investors simply do not take kindly to countries that try to bail on their financial obligations, even if the default happened decades (or generations) ago. To rejoin the global financial markets as a member of good standing, a country that has defaulted on its external debt first needs to find some kind of solution with its existing creditors.

Kostolany was well aware of this fact, and he also had the rare gift of spotting opportunities while they were still hiding behind the horizon.

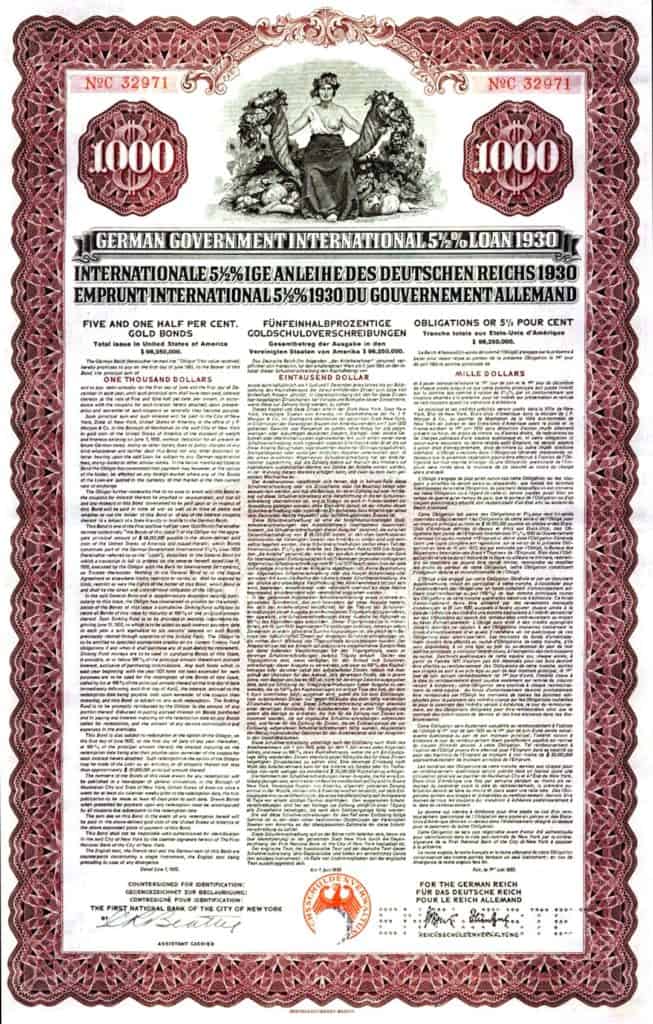

After the Second World War, Kostolany picked up defaulted German bonds – and crucially those that Germany had issued to foreign investors, the so-called "Young Bonds". These had been issued by the German Reich in 1930, to pay reparations for the First World War over a period of 35 years. They were named after Owen D. Young, an American industrialist who advised five US presidents and helped negotiate German reparations. Adolf Hitler defaulted on these bonds after coming to power and called them "illegitimate", the most favoured term any tinpot dictator uses to this day to wiggle out of obligations their predecessors ran up. Kostolany believed that eventually, these bonds were going to be paid after all.

Sticking to debt that had been issued to foreign creditors was crucial for making this investment work out. Any country is free to screw its local population by defaulting on domestic bonds – that's tough luck for the citizenry, who at best have recourse at the ballot box. However, if a bond is issued to a foreign investor, the matter becomes an entirely different one. A country that wants to regain unlimited access to international financial markets needs to find a solution for its foreign-issued debt.

Kostolany, who was of Austro-Hungarian Jewish heritage, believed that the German people were going to get back on their feet, and that they were eventually going to put right their nation's defaulted external debt. In 1946, he picked up Young Bonds for 250 French francs each.

Imagine placing a bet on Germany at a time when the country was literally bombed-out and the world's no. 1 pariah state. Speak of a contrarian bet! Kostolany hoped to eventually recoup the bond's nominal value of 1,000 French francs, which would have made him three times his investment.

Instead, he was able to sell his bonds for a staggering 35,000 French francs each in 1950. They weren't repaid at the time, but the market had latched on to the fact that they would eventually be repaid. The price was propelled upwards on the bond market, and it was possible to sell the bonds at a higher price before they were actually repaid. Kostolany made 139 times his money in less than five years. Not only had he been right about the Germans honouring their obligation, but he was also lucky to benefit from the strength of the newly created Deutschmark.

One of the pre-Hitler 1930 German bonds that were eventually repaid.

The defaulted German bonds were Kostolany's investment coup of a lifetime and transformed his life.

Little did he know that he was going to land a similar coup a few decades later.

A belated present from the Russian czars

During the 1980s, Kostolany again made nearly 100 times his money by investing in distressed bonds that virtually no one else believed would ever regain any significant value.

During the October Revolution of 1917, Russia had defaulted on foreign bonds issued by the czarist empire. The new Soviet government simply declared these bonds invalid because they had been issued by an "illegitimate" administration. Sounds familiar?

Despite the default, the czarist bonds continued to trade on the Paris Stock Exchange. It was easy to pick them up through orders via a bank or broker. Kostolany purchased them for as low as 1% of their original issue price ("nominal value") or 5 French francs each, and he invested 40,000 Deutschmarks.

Just as Kostolany had expected, the Soviet Union did eventually fall, and the newly formed country of Russia wanted to properly rejoin the international financial markets. In the mid-1990s, Russia wanted to place a Eurobond issue, which first required taking care of the defaulted bonds that were in the hands of European owners. As part of a settlement, the czarist bonds were eventually repaid at 100% their nominal value or 500 French francs each, at a cost of around USD 600m. The owners forgave Russia all the accumulated interest (which would have been a multiple of the bonds' nominal value), but at least they were repaid the principal capital. Kostolany's 40,000 Deutschmarks had turned into 4,000,000 Deutschmarks. He had just turned 90 at the time, and the magazine column about his coup raised eyebrows across the entire German investor community.

Once again, a crisis-ridden country that decided to put its house in order allowed Kostolany to make out like a bandit.

The repayment of the czarist bonds was all over the news.

My long-standing attempt at emulating Kosto's coup

I probably started reading Kostolany's books when I was 14 or 15 years old, and I was lucky enough to meet him in the early 1990s. We had a shared interest in a highly controversial German company (relating to East German expropriation claims), though we both ended up losing money.

It was only after his death that I came across defaulted Cuban bonds. Had I discovered them earlier, I would have loved telling Kostolany about it.

The starting situation sounded oddly familiar:

- Bonds issued to foreign investors.

- Bonds defaulted after a dictator took over, because he called them "illegitimate".

- Bonds continued to trade on a stock market.

My interest was piqued, and I purchased my first defaulted Cuban bonds in 2002. Because of luck more than anything else, I came across those bonds at a time when the market had temporarily lost interest. When I started to research them, these bonds were available in large numbers and at a relatively low price. And I did buy them in large numbers!

The arrogance of youth also played into my investment. I was 26 at the time. Fidel Castro was 75. I figured that I was going to outlive the socialist bastard and that Cuba was eventually going to agree to some kind of settlement.

I did end up outliving Castro, but the bonds have been sitting in boxes ever since. My aim to eventually get repaid as part of some form of debt compromise has not worked out – yet! It's been 18 years and counting. I am under no illusion that I should have simply bought Apple stock instead. Then again, there are other Cuba investors who have been onto this for much longer, including a financial institution in New York that must be the world's most successful investor in rare, exotic defaulted debt. That institution once turned USD 3m into USD 200m by buying up so many czarist bonds that they ended up WEIGHING their inventory of bonds rather than to count them.

As a closer inspection of the events that have taken place during the past decade shows, I wasn't entirely on the wrong path:

- Since 2011, several classes of Cuba's foreign debt have been settled.

- Investors are still interested in defaulted Cuban debt, and there remains a market for these instruments. As I uncovered in my recent research, there is even a listed financial instrument that is a pure play on Cuban debt! It's largely illiquid and difficult to trade, but these things can also change and anyone with a gusto for such speculations does have the option to buy into this opportunity through a recognised exchange. There is also a focussed investment fund for Cuban debt.

- As I've learned in recent weeks through some well-informed circles, new developments are likely to bring this speculation back to the fore before the end of 2020. This year and next year should be interesting for holders of Cuban claims.

With new developments on the horizon, I had a good enough reason to sit down and write about it.

Cuba is an example – the same lessons can be applied elsewhere

Let me be very clear and upfront about this. For most of my readers, Cuban debt will not be a suitable, viable investment. The practicalities involved with buying and selling are nothing short of horrendous, and that's if you even manage to find anything to buy at all.

However, there are also a few general lessons from this particular investment case, which we might be able to apply to some of my future, more liquid investment ideas that are cut from the same cloth.

Defaulted sovereign debt can be a lucrative asset class and one that most investors have no idea about. Would you have known that it exists?

That's why I sat down to produce a 56-page Cuba report. My latest piece analyses the opportunity of investing in defaulted Cuban debt, and it also briefly looks at Cuban land expropriation claims. I believe this is currently the single most comprehensive, up-to-date document you can find about this subject – anywhere in the world!

The report also describes the general notion of investing in defaulted debt, which you can then apply to the case of other defaulted countries. Members of my website (USD 49 p.a.) can download the entire 56-page report.

Watch this space for more

For distressed debt investors, opportunities never run out. Every other year, new countries join this illustrious club of outcasts – most recently Venezuela, Argentina, Iran and North Korea. All of them are about as salubrious as Germany must have been in 1946. Going where others don't dare to tread is part of the investment case.

The crucial aspect for investors is to learn about such opportunities and to get their timing right.

As Kostolany would have put it: You need to buy into such opportunities when "shaky hands" want to sell, and then "go to sleep on them" for a few years. Eventually, the alarm bell will go off, and you'll find that you have made lots of money by going against the conventional wisdom.

With distressed Cuban debt and similar claims against the Cuban government, the same might just happen in the not too distant future. If or when it does, I'll certainly raise a toast in Kostolany's honour. He's taught many of us invaluable lessons, and I hope to now pass on a few of them to other investors.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year