How about sending some of your savings to Nigeria?

Do you fancy owning an unlisted Nigerian stock – with no daily price and no organised market?

What if it only worked through Nigerian middlemen?

Doesn’t it all sound rather tempting?

Surprisingly, some people are currently gagging to be part of this scheme. Even more surprisingly, they aren’t gullible private investors, but sophisticated players working at some of the world’s most successful fund management companies.

Incredibly enough, I can’t blame them.

I was offered this particular opportunity through a contact in New York’s hedge fund circles, and I can see why investors are chomping at the bits to get in on this.

They are trying to be part of an opportunity that is set within a decades-long trend. Had you participated in similar schemes around the world over the past three decades, you’d probably be sitting on a decent amount of cash by now. Nigeria is only the latest such opportunity within an industry that has repeatedly produced spectacular results for investors.

What’s it all about?

The Nigerian Stock Exchange is turning into a privately owned enterprise, instead of the non-profit club that it's used to be.

The newly formed company will then carry out an IPO, which means that anyone will be able to buy and sell the stock of the company that owns and operates the stock exchange. Famous examples of publicly listed stock exchanges are the London Stock Exchange (ISIN GB00B0SWJX34), Deutsche Boerse (ISIN DE0005810055), and the New York Stock Exchange (ISIN US45866F1049). All of them are entities that you can become a shareholder of.

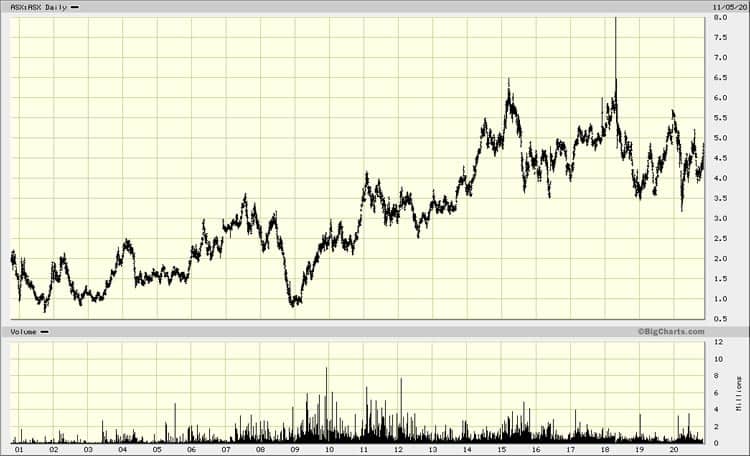

These companies have proved to be great investments over the past decades (see the charts further down).

Which is why, using the Nigerian Stock Exchange as a current example, I'd like to introduce you to this particular sector.

There's also one particularly interesting opportunity that I'd like to point you to – it is hiding in plain sight in Europe, and there's no need for you to send any cheques to Nigeria!

The world’s publicly listed stock exchanges

Our journey through this peculiar industry has to start in Sweden in 1993.

Sweden isn't usually known for capital market innovations. However, some 27 years ago, the country did manage to write stock market history and launch an entirely new trend.

Until the early 1990s, the world's stock exchanges were usually organised as non-profit, mutual organisations owned by banks, brokers, market makers and other key market participants. These markets operated as a quasi-membership club, and its members enjoyed exclusive trading privileges. Under the old model, ownership and membership were bundled together.

The Stockholm Stock Exchange was the first organisation to break with tradition and turn itself into a publicly traded, for-profit company. The legal process for carrying out such a switch is called "demutualisation". The subsequent IPO of the newly formed company created global attention and led to similar deliberations in the boardrooms of other exchanges.

Over the subsequent two decades, a wave of demutualisations and IPOs of other stock exchanges followed. Turning a member-owned stock exchange into a publicly listed company became a global trend.

Stock exchanges are gentlemen's clubs no more.

A global phenomenon (but little-noticed by the wider public)

Among the stock exchanges that decided to demutualise and "self-list" were:

- London Stock Exchange

- New York Stock Exchange

- Chicago Mercantile Exchange

- Euronext (Netherlands, Belgium, France)

- Deutsche Boerse (Germany)

- Australia Stock Exchange

- Toronto Stock Exchange

- Hong Kong Stock Exchange

- Singapore Stock Exchange

- Tokyo Stock Exchange

In a second wave, stock exchanges in emerging markets followed suit:

- Brazil (B3 - Brasil Bolsa Balcão, publicly traded)

- India (Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange, demutualised but not yet publicly traded; though an IPO beckons for the National Stock Exchange)

- Malaysia (Bursa Malaysia, publicly traded)

- South Africa (Johannesburg Stock Exchange, demutualised but not yet publicly traded)

- Philippines (the Manila Stock Exchange and the Makati Stock Exchange merged to form the Philippines Stock Exchange, publicly traded)

- Chile (Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago, publicly traded)

- Pakistan (PSX, publicly traded)

More exchanges are added each year. The trend is reaching the farthest corners of the world.

Why the ongoing rush to demutualise and list the stock?

It simply made good business sense, and it even became necessary for sheer survival.

The New York Stock Exchange as a case study

In the olden days, a mutual or cooperative structure was often the best way to organise an exchange. However, as markets became more sophisticated, these organisations often experienced that interests of different member groups diverged. As a result, decision-making processes became slow and, in some instances, conflicts arose.

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) provided one of the best examples.

At the end of the last century, the NYSE had nearly 1,400 members. The majority of them were floor traders, while larger brokerage firms made up only a minority. The world's largest stock exchange faced a growing need to lower trading costs in order to attract institutional investors; however, the floor traders used their voting power to keep trading costs high since it lined their own pockets. The large brokerage firms worried about the NYSE losing its market position.

Eventually, the competitive pressure from newly launched electronic exchanges led to wholesale changes. The existential threat posed by these electronic platforms proved to be the catalyst to make the change-averse organisations change after all.

In 2005, the NYSE turned itself into a for-profit company and merged with a leading electronic trading platform, Archipelago. The following year, it went public, trading as NYSE Group at the time. Another year later, the company merged with Euronext, the European exchange that had come out of the Netherlands, Belgium and France. The newly formed company became NYSE Euronext, the first transatlantic stock exchange. In 2013, the Intercontinental Exchange, a futures exchange based in Atlanta, acquired NYSE Euronext in a deal then worth about USD 8bn. A year later, Euronext was spun off again into a separately listed entity. The NYSE remains part of the publicly traded Intercontinental Exchange.

Had the NYSE stayed a membership-based organisation, more agile competitors would probably have pushed it out of business by now.

Also, as the example shows, the 2000s and 2010s have seen a lot of M&A activity in the stock exchange sector – with lucrative bids for entire companies.

Lean, agile and (often) highly profitable businesses

The for-profit exchanges of this world have made operating a stock exchange a highly competitive business. If a stock exchange doesn't offer slim trading costs and innovative services, business can easily gravitate elsewhere. In the day and age of electronic trading platforms, stock exchanges need to remain hyperalert to what their competition is doing.

Demutualising and going public enabled these staid organisations to create more agile decision-making processes, and it also allowed them to raise funds to invest in improving their products and services.

At the same time, these exchanges continued to benefit from their prior status as quasi-monopolies. After all, a strong market position built over decades or even centuries doesn't slip away overnight.

Stock exchanges are a particular form of legal entity. To operate a stock exchange, you need to be a "recognised stock exchange" in your country – a legal term that has serious weight. Think of it as the equivalent of having your organisation recognised as one of the official faiths of your country, combined with an ability to collect church tax. You may yet lose believers over time if you screw up too badly, but your starting position will be a strong one, and the money will roll in from a clientele that is closely tied to you (at least initially).

Companies with "recognised stock exchange" status effectively enjoy a business with a moat. On the one hand, the plethora of exchanges around the world and electronic trading means that all exchanges face competition. On the other hand, it is very challenging to create new upstarts in this industry – the barriers to entry are extraordinarily high. Thus, competition is mostly limited to the established players.

Also, exchanges do enjoy a few features that other business owners can only dream of:

- Nowadays, exchanges are effectively a software business. Most exchanges are run off computer servers so there is hardly a need for investments in physical assets.

- New products can be created out of thin air – literally! Dreaming up a new derivative that appeals to traders can be enough to create a new line of income.

- More and more assets get traded on exchanges. 20 years ago, no one thought of trading carbon credits. Today, these assets require exchanges to change hands. As the world economy becomes more sophisticated, a growing number of assets are likely to be traded electronically through organised exchanges. An exchange that already trades stocks can much more easily add a division for trading other assets, compared to someone else trying to set up such a market from scratch.

- The economies of scale are tremendous. Once a stock exchange has covered its fixed costs, additional revenue disproportionally adds to the bottom line. That's why the stocks of more successful exchanges have done so well. E.g., during the 2004 to 2008 boom, while the German DAX rose by a factor of three, the stock of Deutsche Boerse went up by a factor of seven.

At the risk of stating the obvious, whether an exchange can take advantage of these opportunities or not is mostly down to the quality of its management.

Those for-profit exchanges that have outstanding management teams have made heaps of money for their shareholders over the past two decades.

It's down to software in a double way – the actual software and the brains behind it.

How did publicly traded exchanges perform for their shareholders?

If you check on the 20 largest stock exchanges in the world, you will find that 11 of them are publicly traded companies.

Given that these stock exchanges are the top 20 globally, it's reasonable to assume that they represent the winners of the past two decades of demutualisation, consolidation, and innovation. There is a strong element of survivor bias built into this selection, meaning this is not representative of ALL exchanges around the world. Still, it’s quite telling to see how well most of them have fared since they went public.

The following charts are listed in order of company size.

1. Intercontinental Exchange (including NYSE)

ISIN US45866F1049

NYSE:ICE

2. Nasdaq

ISIN US6311031081

Nasdaq:NDAQ

3. Japan Exchange Group

ISIN JP3183200009

JP:8697

4. London Stock Exchange

ISIN GB00B0SWJX34

UK:LSE

5. Shanghai Stock Exchange

State-owned

6. Hongkong Exchange & Clearing

ISIN HK0388045442

HK:388

7. Euronext (France)

ISIN NL0006294274

FR:ENX

8. Shenzhen Stock Exchange

State-owned.

9. TMX Group (= Toronto Stock Exchange)

ISIN CA87262K1057

CA:X

10. BSE (Bombay Stock Exchange) and 11. National Stock Exchange

The two Indian stock exchanges have demutualised, but are not yet publicly traded. The National Stock Exchange is rumoured to be preparing its IPO right now.

12. Deutsche Boerse

ISIN DE0005810055

XE:DB1

13. SIX Group (Switzerland)

Demutualised but not yet publicly traded.

14. South Korean Exchange

Demutualised but not yet publicly traded.

15. Nasdaq Nordic Exchange

This exchange comprises the stock exchanges of eight countries: Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Iceland, and Armenia.

The company is 100% owned by Nasdaq (see spot #2).

16. ASX Ltd. (Australian Securities Exchange)

ISIN AU000000ASX7

ASX:ASX

17. Taiwan Stock Exchange

Demutualised but not yet publicly traded.

18. Brazil Stock Exchange ("B3 - Brasil Bolsa Balcão S.A.")

ISIN BRB3SAACNOR6

BR:B3SA3

19. Johannesburg Stock Exchange

Even though it is only #19 globally, it is #1 in Africa.

20. BME (Bolsas y Mercados Españoles)

ISIN ES0115056139

BMAD:BME

Where is the next such opportunity?

I am definitely not going to suggest you send money to Nigerian middlemen in order to buy an unlisted Nigerian stock.

That’s a business that investors in pioneer markets and specialised hedge funds are currently pursuing. They have latched onto the fact that it’s possible to buy stocks of the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE) before the IPO is carried out. There is a grey market for NSE stocks, because some of the local brokers and institutional investors that receive shares as a result of the demutualisation are willing to sell ahead of the IPO.

The last I heard, these shares were changing hands at a price/earnings ratio of about 9. That doesn’t strike me as particularly cheap, when you factor in that the stock is entirely illiquid because it’s not listed yet. Never mind restrictions on ownership, which limit outside investors to holding no more than 4.99%.

Still, serious investors are looking at this right now because in the past, so much money was made if you just managed to get in early. Other notable examples include the stock exchange of Kuwait, which saw its shares rise by 500% after it became available in October 2019, or the stock of the Argentinean BYMA AR, which rose 900% in nine months after getting its listing in 2017.

Given its position as one of the leading financial gateways to the booming economies of Africa, the stock of the Nigerian Stock Exchange will probably do well in the long run. It could be a cunning trade to get in before the IPO – but I don't view it as feasible for private investors.

The good news is, a not too dissimilar opportunity exists in Europe – and it’s much easier to access.

The stock exchange that I've got in mind has the following features:

- Lowest EV/EBITDA valuation of all listed stock exchanges in the world.

- 6% dividend yield.

- P/E 8.

- Leading market position in its region.

- Easily tradable through an OTC listing in Frankfurt.

This stock exchange has considerable growth potential. Admittedly, it’s still early in the cycle of spreading its wings and modernising, and its national government remains the largest shareholder. However, that’s where the opportunity lies. If everything was in perfect shape already, the stock would have gone through the roof by now. Stocks go up as companies modernise and resolve their structural faults.

I featured the stock of this particular stock exchange in much detail in July 2020, as part of my ongoing series of research reports. Reading how the opportunity in Nigeria is peddled around right now, I figured it’d be worthwhile pointing it out once again. Download it now if you haven't already!

Alternatively, I could put you in touch with a few folks in Nigeria…

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just USD 49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports