During the 1990s, Martin Ebner was one of the world's most widely followed activist investors and financial entrepreneurs. Even outside of Switzerland, everyone reported about him, including the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal.

During the past decade, Ebner has not been in the limelight to quite the same degree, not even in his home country. Outside of Switzerland, many younger investors would not even know who he is.

Whilst media reporting about him subsided, the 76-year-old propelled his net worth to a new record: CHF 5bn (USD 5.2bn). Not a bad achievement for someone who started his career with a loan, and nearly lost everything in the 2002 crash.

A fair amount of public material exists about Ebner, but no one seems to have looked at the entirety of his career and his key investments, while analysing what ordinary investors can learn from him. Luckily, you've got Undervalued-Shares.com!

Ebner in 1996 (source: Amazon).

Humble beginnings

Martin Ebner didn't exactly inherit wealth or successful entrepreneurship. His father had spent decades working in the same printing company, and his mother took care of their four children. The family reportedly lived a modest middle-class life "without any unnecessary luxuries", according to the unauthorised 1996 biography, "Das schnelle Geld" ("The fast money"), which was only ever published in German.

Ebner was, however, lucky to have a neighbour who introduced him to the concept of managing money on behalf of other people. In a rare interview with German-language newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) on the occasion of his 75th birthday in August 2020, Ebner mentioned how the mentoring by his neighbour started his career.

During his time at university in Zurich, Ebner started to build his personal network, and befriended someone who would later also become one of Switzerland's richest investors – Christoph Blocher, to whom this article will get later. However, at the time, neither Ebner nor Blocher had much to their name.

Ebner started his career as a banking apprentice at Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA), back then one of the country's largest banks. Later, he added a 12-month stint at Banque National de Paris, before checking out London's City for six months by working at the SKA's UK subsidiary.

So far, so conventional.

When Ebner decided to spend some time studying in the US, he did so at the little-known College of Business Administration in Gainesville in Northern Florida, rather than Harvard or Princeton. One of the non-academic insights he is said to have gained there was the value of networking. Upon his return to Switzerland in the mid-1970s, Ebner put his existing network to the test; using his contacts at Vontobel, he landed a job in the bank's new equity research department. Back in the days, equity research in Switzerland was a clubby affair where analysts never said anything that could upset the apple cart. Ebner brought a different modus operandi to Vontobel, and the market took notice. To this day, Ebner is credited with single-handedly modernising equity research in Switzerland.

When his former employer, SKA, was embroiled in a financial scandal in 1997, the Swiss banking establishment tried to hush things up as usual. Using his understanding of balance sheets, Ebner worked out the "real" loss that SKA had suffered. He disclosed his findings to his clients and advised them to sell, contrary to everyone else. The sleepy world of Swiss equity research and banking had not seen someone act with such derring-do. Ebner's call turned out spot on, and Vontobel experienced an influx of new clients who were excited about gaining access to edgy equity research.

Ebner became a rising star within Switzerland's financial services, but he wanted more. In 1984, he approached the patriarch of the Vontobel family to ask for more influence and a more prominent role. In effect, he wanted nothing less than to effectively take control of the bank and even be put ahead of his former fellow student, Hans-Dieter Vontobel.

The discussion was said to be "fiery", although no details were ever confirmed. Ebner got fired on the spot, that's all that can be said for sure.

He did take one valuable asset with him, though. Working for Vontobel's wealth management and equity trading division, Ebner had built relationships with wealthy private clients and powerful institutional investors in Switzerland and abroad.

With their help, he was going to do something revolutionary – establish a new Swiss bank to pursue business Ebner-style.

A bold entrepreneurial idea

In the late 1970s, Ebner got to know two Swedes who were going to become critical partners in his later career steps:

- Erik Penser, an exceptionally gifted equity trader who created his own securities firm to promote Swedish equities internationally. Penser also dabbled in shareholder activism, which made him the equivalent of a billionaire at the time.

- Johan Björkman, who alternated between working as a journalist and dealing with securities. Björkman was also a partner in Penser's firm.

The three had met during one of Penser's research trips to Zurich. "If you end up leaving Vontobel, we'll be delighted to become your partners", the two Swedes reportedly told Ebner ahead of his fiery Vontobel meeting.

Setting up a new bank in Switzerland at the time required CHF 20m in equity. While Ebner's Swedish friends could have easily provided such a sum, the Swiss regulator would have never allowed a new bank to be under foreign majority control.

One of the valuable contacts Ebner had cultivated during his days at Vontobel was Andreas Reinhart. His Winterthur-based family was such a big trader in commodities and securities, through its firm Handelshaus Gebrüder Volkart, that it counted as an institutional investor.

Thanks to Reinhart's influence, Ebner was able to mobilise a CHF 7m loan for himself from Schweizer Bankverein (SBV), the country's then second-largest bank. The Swedes (40%), Ebner (30%) and Reinhart's family holding (30%) registered BZ Bank on 15 May 1985.

What followed was one of the fastest cases of large-scale wealth creation that Switzerland had seen up to this point. As the Financial Times reported in late 1985, the arrival of BZ Bank "signalled the rise of a younger generation that is eager to utilise the opportunities that stem from the internationalisation of equity markets".

The newly-formed bank pursued the goal of innovating the staid world of Swiss banking and equity trading, and innovate it did!

Using relationships to build a fortune

Following decades of glacial change, the world of Swiss banking existed in a kind of content stupor. Clients were overcharged and underserviced, which is where Ebner spotted his opportunity. Trading equities on behalf of clients, providing research, and wealth management services became the cornerstones of BZ Bank.

BZ Bank charged its institutional clients 0.5% of each equity trade, seemingly 2-5 times more than what existing Swiss banks charged. However, large Swiss banks at the time engaged in the practice of buying stocks for their own book first before immediately selling them on to clients at a higher price – a practice that is now illegal, but common at the time. In line with his habit of saying things as they were, Ebner wanted clients to be clear what his services consisted of and what his bank charged. In the end, paying 0.5% commission and getting good advice may have been cheaper than the seemingly lower fees charged by other banks once the "hidden" fees were accounted for.

Using the network that he had built during his time at Vontobel, Ebner assembled a high-calibre and diverse list of key clients:

- Switzerland's largest pension fund for government employees.

- Marc Rich, the enfant terrible of the international commodities world.

- Most of Switzerland's major insurance companies.

- Anglo-Saxon players like J.P. Morgan, Citibank and Drexel Burnham Lambert.

- Nomura in Japan.

- Allianz in Germany.

Even a fellow student and personal friend formed part of the major clients. Christoph Blocher, Ebner's close friend from university, had staged a coup at Ems-Chemie Holding (ISIN CH0016440353, SWX:EMSN), the medium-sized Swiss company that he worked for. Unlike Ebner's efforts at Vontobel, Blocher's agitating succeeded, and he took control. The transaction had made him a wealthy man, and there'll be more about Blocher's role in Ebner's business life a little later.

BZ Bank came up with an innovation that made Ebner the Cathie Woods of his days. Instead of just sending out analyst reports, BZ Bank offered its clients to come along when their equity analysts met with companies. This was unheard of at the time, but highly appreciated by clients. The media widely reported about it, which helped build the brand and generate a lot of new client interest.

With its transparent services, strong client relationships and innovative research services, BZ Bank was off to a good start. A short 3.5 years later, it was already worth CHF 500m. Ebner owned 20% of the enlarged share capital, meaning his net worth had increased by CHF 100,000 per day for each day the bank had existed up to that point. In an era that predated the kind of rapid entrepreneurship we know today, Ebner's rise to become a centimillionaire was a rare home run in Switzerland's conservative business community. The more technical details of BZ Bank's meteoric rise as a business were analysed in the little-known German-language book "Wie die Geldmaschine von Martin Ebner funktioniert" ("How the money machine of Martin Ebner functions"), published by Willy Huber in 1999.

Ebner had yet to add a final missing ingredient: a move that was going to put his bank's fortune into overdrive mode. It was a move that, to this day, every private investor should learn from.

Ebner's most important talent

When asked for his #1 factor for success, Ebner would point to his ability to spot structural changes and ride them for years.

What does he mean by that?

"Everyone is focussed on short-term cyclical trends. Everyone is an 'expert' in doing that. However, the much more demanding task is to recognise large-scale structural changes before they happen. If you focus on that, you'll have less competition."

This chimes well with the two previous parts of "The world's best investors". Karl Ehlerding spotted the structural changes coming the way of publicly listed housing associations, and his 20 years of riding this wave through investing in the right stocks made him a billionaire. Nicholas "Nick" Roditi spent his entire investing career identifying upcoming structural changes and riding them for years through whatever securities he had to buy in order to latch onto a new macro trend.

During the early phase of Ebner's career, Switzerland's stock market was split into different share classes for Swiss citizens and international investors. Ebner's master stroke was to recognise that this split was going to come to an end eventually, which made for an amazing, large-scale arbitrage opportunity that could be exploited with little risk.

During the 1970s, the Swiss government had feared that Arab investors could use their petrodollars to purchase control of the crown jewels of Switzerland's corporate landscape. To protect the small country from foreign takeovers, companies like Ciba-Geigy, Sandoz and Swiss Re introduced a share class that could only be registered to a new owner at the discretion of the company's board. Such approval was then tied to being a Swiss citizen, and these shares often came with multiple voting rights. Everyone else could purchase shares in the same companies on the stock market, but they usually came with lesser voting rights and/or a restriction to owning no more than 5% of votes.

The domestic shares had a smaller audience of potential investors, which is why they were cheaper. They often traded at just about half the price of the shares that could be freely bought and sold by international investors.

Ebner had seen financial markets elsewhere modernise, and he predicted that Switzerland would eventually come under pressure to do away with the discrimination of foreign stock holders. At the first sign of such a step, the valuation gap between both share classes would then narrow, and eventually disappear once share classes were unified.

Instead of merely waiting for that to happen, Ebner used his BZ Bank to actively push for it. By creating new derivatives, he enabled *foreign* investors to purchase a right to the domestic shares without having to purchase the domestic shares themselves. This undermined the existing system, gave foreign investors an exciting new product to bet on change coming to Switzerland's financial markets, and it was an unheard-of innovation that further increased Ebner's notoriety. The idea led to the creation of several dedicated investment vehicles at BZ Bank, raising billions from investors both in Switzerland and abroad. The bank turned into one of the largest, most influential forces for change in Switzerland's financial industry.

Along the way, Ebner became a billionaire and corporate activist.

Not all of his activities succeeded, though. As a young student, I witnessed Ebner in the most epic battle of his career, and I did so literally from a front row seat.

David vs. Goliath ambitions

During the early 1990s, Switzerland's banking landscape was dominated by Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft (SBG), Schweizerischer Bankverein (SBV), and Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA). With CHF 400bn of client assets, SBG was Switzerland's largest bank when measured by the amount of wealth managed on behalf of others.

After the stock market crash that followed the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990, the stock of SBG traded at a low valuation. Spotting an opportunity to manage both SBG itself and its client assets in a more efficient way, Ebner used his own bank's financial heft to purchase an initial stake. He launched what to this day remains one of the greatest corporate activist battles that Switzerland had ever seen (if not the greatest one).

As a protection against petrodollars taking control, SBG had introduced a domestic share class during the 1970s, which came with a five-fold voting right. In 1990, the board implemented a 5% voting rights restriction as a further safeguard against outside control.

Ebner considered such measures a barrier to the creation of shareholder value, and he publicly took on the 22-strong board of directors to argue for change. Speaking in his role as a new major investor in SBG, Ebner said: "I am not excluding the possibility that, over time, we will reduce the number of board members." It was a thinly veiled swipe at the inflated number of directors who lived off shareholders' money, and another outrageous statement in the otherwise much more diplomatic Swiss banking industry. Ebner criticised the bank for generating an annual return on equity of just 5%, and he was pushing to set a target of 15%.

The subsequent activist battle made Ebner the equivalent of a modern-day Robin Hood of Swiss investors – David against Goliath. It culminated in a history-making 22 November 1994 meeting of shareholders, which I attended as a 19-year-old student.

With 10,000 shareholders in attendance, the event had swollen to a multiple of its usual size. International media had flocked to Switzerland to report, and Ebner had become a rockstar who performed in an arena that usually served as Zurich's concert venue.

Sadly, it wasn't supposed to be at the time. The proxy battle was "won" by SBG – if only by a small margin. Ebner's subsequent legal challenge was probably well-founded because there was a good reason to suspect voting irregularities, but the court case became so complex that few people understood what it was all about. BZ Bank's vehicle for purchasing SBG stock upped its investment further, but the bank's earnings came under pressure and the entire investment case started to fall apart.

Ebner never succeeded with his effort to gain control of SBG, but his campaign led to the 1998 merger of SBG with SBV – which today is known as UBS, one of the world's largest wealth managers.

As Bloomberg mentioned in a 13 June 2022 article, "Ebner was a major driver of corporate change in Switzerland". NZZ, the grand dame of Switzerland's newspapers and the country's only internationally read daily publication, granted Ebner the ultimate accolade when on 13 June 2022, it reviewed and summarised his career as follows: "During the 1980s and 1990s, Ebner put radical demands in front of Swiss CEOs. Over time, most of his demands were fulfilled." Ebner had used his voting rights to shake up corporations like Swiss Re(ISIN CH0126881561, SWX:SREN), Roche (ISIN CH0012032048, SWX:ROG), ABB (ISIN CH0012221716,SWX:ABBN), Alusuisse, and Lonza Group (ISIN CH0013841017, SWX:LONN).

As a visionary and innovator, Ebner was sometimes ahead of his time. As an activist investor, he stepped on powerful peoples' toes and faced up to the inevitable pushback. Time proved him right, though.

Along the way of bringing such radical change and innovation to Switzerland's financial markets, Ebner first made but then also very nearly lost a fortune.

At the turn of the millennium, Ebner's investment empire managed CHF 30bn in client assets. The Dotcom Crash of the early 2000s, however, nearly cost him his empire. With BZ Bank and its investment vehicles operating with leverage at the time, Ebner in 2002 needed what was essentially a "bailout". As Ebner admitted later, he had completely underestimated that during a crash, the share prices of high-quality blue-chip companies would also suffer.

To keep his empire from falling apart, Ebner made a deal involving his stake in the Swiss real estate firm, Intershop Holding (ISIN CH0273774791, SWX:ISN), and his long-standing friend, Christoph Blocher. His buddy from university had become a multi-billionaire thanks to his flourishing stake in Ems-Chemie Holding. Following his palace coup at the company, Blocher had taken the medium-sized Swiss firm to new heights altogether, and he helped Ebner with a transaction that saved Ebner from having to pay a CHF 50m tax bill, which in turn gave him the breathing room to take his investment group through the crisis of the early 2000s.

Ebner today

Since his near-bust in the early 2000s, Ebner has recovered through a number of successful investments – and then some.

In late 2003, he used the remnants of his formerly large fortune to purchase a 12.4% stake in Converium, at the time a publicly listed Swiss reinsurance company. During the preceding crash, Converium had been badly hit and needed a rescue financing package. Ebner, in his typical style, agitated for change at board level. He later upped his stake to 20%, some of it through options as a way to achieve a higher leverage effect. In 2007, he helped the French reinsurer, Scor SE (ISIN FR0010411983, FR:SCN), to build up a position of almost 33% with a controversial option deal, which contributed to a collapse of Converium's management and a hostile takeover.

As Ebner said in his June 2020 interview with NZZ, the risky heavy weighting on his Converium investment was key to reversing his personal fortune. Again, a concentrated portfolio approach did the trick – and you just need to land such a home run once.

In 2006, Ebner rescued the ailing Swiss low-cost airline, Helvetic Airways. The privately held company has since become extremely successful, but few figures are available about Ebner's investment.

At the end of 2021, Ebner sold a 23% stake in a publicly listed Swiss pharma company, Vifor, to an Australian biotech firm, CSL. The USD 10bn transaction was a triumph for Ebner, given that he had spent a decade working on this investment. He had first bought a 3% stake in 2011, which he then gradually upped. This allegedly involved derivatives and debt, but details are disputed. It's clear, though, that this transaction was key to making Ebner richer than ever before.

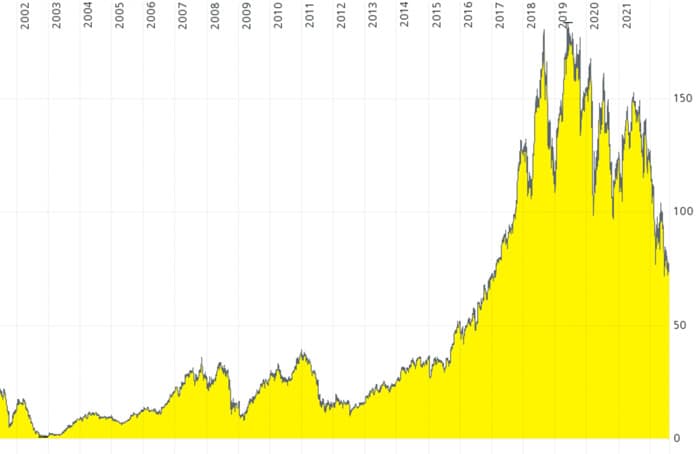

Anyone interested in takeover candidates should probably take a look at Temenos (ISIN CH0012453913, SWX:TEMN), where Ebner holds a 10% stake. The company is specialised in enterprise software for banks and financial services. Potential bidders have been circling the company, and since it seems that Ebner is gradually cashing in his chips, there is a good chance that Temenos will eventually attract a bid. Ebner first disclosed a 3% stake in the company in 2012, when the stock was trading at CHF 13 compared to now CHF 77.

Temenos.

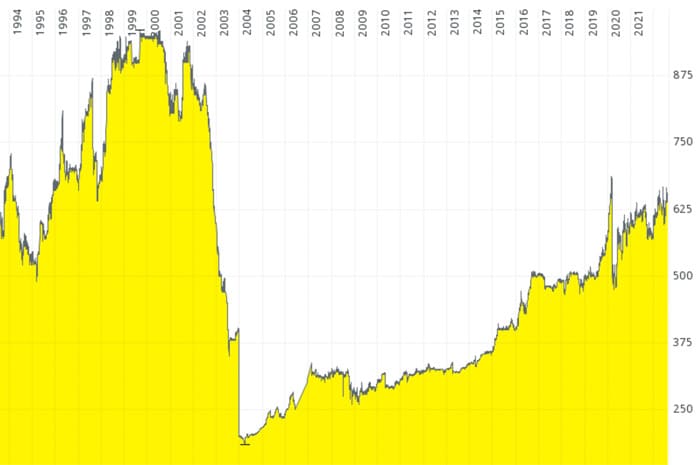

Another key holding of Ebner's holding company, Patinex, is Intershop Holding (ISIN CH0273774791, SWX:ISN). Ebner has been a shareholder of the company since the mid-1990s, and he is now by far the largest investor with a 35% stake worth about CHF 400m. The stock has a 4% dividend yield and is one of the smarter ways to put some money away for a rainy day by buying into Swiss real estate. The recent stock market turbulence has left Intershop Holding's share price unfazed. It trades near its record high, which could be an indication that there is more to come. It'd be hard to imagine that Ebner will cash in this investment. Where else other than Swiss real estate would he put money in for safekeeping?

Intershop Holding.

On 25 August 2022, Ebner will turn 77.

Two months ago, Ebner made a major step towards securing his legacy: by selling 70% of his 100% stake in BZ Bank, he ended his active 37-year involvement with the bank that he founded.

Throughout his career, Ebner has been given many labels by the media, his enemies, and even his allies, with "trendsetter", "raider", and "outsider" representing just some of these terms. It looks like another label has to be thought of soon, as Ebner is reportedly getting ready to ride off into the sunset and create some kind of philanthropic legacy. He can do so from the position of someone who took the idea of "finish on a high" to heart. I wouldn't be surprised if in that part of his career, he also turned out an innovator.

Following Ebner's extraordinary and controversial, but ultimately extremely successful career as a public equity investor, one can only wish him well for this next chapter in his life.

7 lessons learned

Which aspects of his rapid (and also subsequent) rise can ordinary investors learn from and emulate?

When looking at the factors that made Ebner's success story possible, I'll begin with a factor that I had already listed in the profile of Nick Roditi:

1. Know the right people

Strong relationships with the right people are extremely valuable, if you can get them.

There are several examples where such relationships helped Ebner to build and protect wealth:

- Ebner got a CHF 7m loan when he had hardly any assets that he could provide as collateral, because he had Andreas Reinhart as a backer.

- BZ Bank's business took off quickly because Ebner brought along relationships with leading institutional investors.

- When Ebner had his close call, his long-standing relationship with Blocher enabled him to mobilise a rescue package.

This isn't always relevant (or replicable) for private investors, and it's not the only factor that led to Ebner's success.

It deserves to be put front and centre, though, when reviewing Ebner's career based on the publicly available material (Ebner himself is widely known to rarely speak to the media these days).

2. Spot structural change, and ride it

As explained above, Ebner's investment strategy consisted of:

- Disregarding short-term fluctuations of the kind everyone worries about.

- Making an effort to locate far-reaching changes before others pay notice.

- Sticking to an investment theme for years.

The protagonists of this three-part investor series all based their strategy on pursuing this kind of approach. This was an entirely accidental overlap, but it does tell us something.

3. Focus, and bet big

As Ebner's unauthorised biography put it: "One of the key pillars of Martin Ebner's textbook career was his ability to focus all his available energy on a single goal."

In his investing, too, did he pursue this kind of focus.

BZ Bank grew quickly because it promoted a limited number of investments and pursued what was effectively a concentrated portfolio strategy.

Yet again, I refer back to the approaches of Ehlerding and Roditi, as well as my Weekly Dispatch of 13 August 2021: "Concentrated bets – how the world's best value investors got rich".

Ebner in 2020 posing onboard a Helvetic Airways plane.

4. Don't have kids

Not everyone will agree with this point, and there are plenty of cases to argue the opposite.

Ebner, though, felt that in order to achieve greatness, all energy needed to go towards his career, and kids would be a distraction.

He and his wife, to whom he has been married for 50 years, have never had children.

5. Cultivate non-senior contacts

Ebner had first-class contacts to senior executives at major institutions.

One the less-known aspects of his successful work is how he utilised contacts to mid-level employees to his firm's advantage.

CEOs do little of the nitty-gritty work but get all the attention, whereas mid-level employees do all the day-to-day work but get barely any outside attention. Ebner made it a policy to cultivate contacts at the mid-level of financial institutions, who felt flattered by his interest. This gave him another lever of influence.

6. Get professional communications training

NZZ once asked Ebner about his #1 personal quality that had helped his career:

"Surely, it's my ability to sell. Generally speaking, I find it easy to establish new relationships. I can approach people and explain background stories to them. However, this requires that you really know what you are talking about."

It is one of the less appreciated factors of Ebner's success that he spent a lot of energy on calculated, professional media work. He regularly attended communication trainings throughout his career, so that he could sway journalists, the public and other critical audiences in his favour.

Also, with his habit to wear a bow tie, Ebner created a personal brand before anyone knew what personal branding was all about – and in the staid world of Swiss banking, no less. The amount of free media reporting that Ebner enjoyed throughout his career cannot be underestimated, since much of it was, in essence, free advertising for his firm. Even today, few in the financial services industry understand the PR term "advertising equivalency value".

As an investor who tried to make other investors back or follow him, Ebner's talent for (and knowledge of) communications and media work was anything but an unimportant factor.

7. Don't wear a watch

Ebner famously never wears a watch. That'd be less remarkable if he didn't live in a country that is famous for its watch industry.

In some way, it's symbolic for Ebner's habit to simply work for however long it takes each day to get everything done. He doesn't differentiate between his work and the rest of his life.

As someone who doesn't wear a watch either, I find that a fun and useful factoid about Ebner's career.

Blog series: The world's best investors

There's more to "The world's best investors" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Another gem from Switzerland

Martin Ebner's entire life revolved around banks. And he was absolutely right – you could do worse than invest in banking "Made in Switzerland".

Here's another stock idea from the Alpine country for you: It's one of the best-known brand names in its sector, and it currently offers the best buying opportunity since the Great Financial Crisis.

Record-low valuation in absolute terms, the prospect of a new multi-year boom for its business, as well as a >6% p.a. dividend yield and massive share buy-backs while you wait…

Accumulate while markets are still under pressure!

Another gem from Switzerland

Martin Ebner's entire life revolved around banks. And he was absolutely right – you could do worse than invest in banking "Made in Switzerland".

Here's another stock idea from the Alpine country for you: It's one of the best-known brand names in its sector, and it currently offers the best buying opportunity since the Great Financial Crisis.

Record-low valuation in absolute terms, the prospect of a new multi-year boom for its business, as well as a >6% p.a. dividend yield and massive share buy-backs while you wait…

Accumulate while markets are still under pressure!

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: