Edwin Dorsey is a present-day wunderkind of the investment world. He publishes an influential newsletter on fraudulent companies, and his Twitter feed is followed by some of the world's most influential investors. Institutional Investor featured him in an in-depth profile on 16 November 2020 when he was just 22 years old!

Dorsey is also a value investor who makes concentrated bets.

He recently disclosed an investment of 50% (!) of his personal portfolio in a single value stock, Twitter (ISIN US90184L1026). Putting half of your money into a single stock is what you could call a truly concentrated investment strategy.

I have been a lifelong believer in concentrated bets and always wanted to share my experiences and observations with my readers. Dorsey's investment in Twitter gave me a reason to finally get on with it.

If you are eager to learn about an investing strategy that is not commonly taught elsewhere, this may be one of the most important articles you have ever read. It won't offer you any fixed, iron-clad ideas, but it'll help you get onto a new path that might work for you.

A common denominator among many successful outliers

Diversify, hedge your bets, spread your portfolio across many stocks. It must be the finance industry's most frequently dished-out advice not to put all your eggs into one basket.

This advice is not wrong per se, but it won't apply to everyone. Everything depends on what you aim to achieve and what your circumstances are. For some, diversifying could indeed be the wrong strategy.

One of the inconvenient truths of the stock market is that very few people get rich through investing. You have a much higher likelihood of getting rich from starting and building a business. Trying to get rich on the stock market is tempting for all sorts of reasons, but it's insanely difficult to say the least.

Some say that spreading your bets and aiming to gradually get rich on the back of the economy's long-term growth is the only way the stock market could ever work in your favour. They aren't wrong, but their theory is up against some serious competition.

If you study the world's greatest investors, you will find that many of them completely ignored all advice about diversification. Going the opposite way led to immense riches, and for quite a few of them, it did so rather quickly.

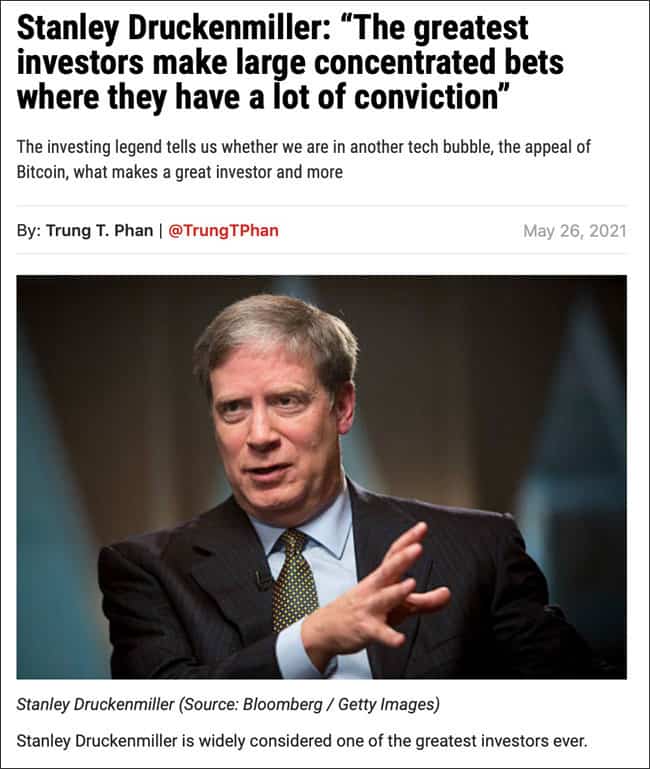

Stanley Druckenmiller, the billionaire investor who rose to fame and wealth alongside George Soros, nicely summarised it in his interview with The Hustle on 26 May 2021:

"When I've looked at all the investors (that) have very large reputations — Warren Buffett, Carl Icahn, George Soros — they all only have one thing in common.

And it's the exact opposite of what they teach in a business school. It is to make large concentrated bets where they have a lot of conviction.

They're not buying 35 or 40 names and diversifying.

I don't know whether you remember that Icahn a few years ago put $5B into Apple. I don't think he was worth more than $10B when he did that.

[In 1992] when I went in to tell Soros that I was going to short a 100% of the fund in the British pound against the Deutschmark, he looked at me with great disdain. He thought the story was good enough that I should be doing 200%, because it was sort of a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

So, [these investors] concentrate their holdings. This is very counterintuitive."

Pretty clear words from someone who has been around for a long time, and who has walked the talk.

Which begs the question, could such a strategy of concentrated bets work for you, too? And if so, what are some of critical factors to make this strategy work?

Triggered by Dorsey's bet on Twitter, I've had a look for useful source material on the idea of concentrated investing, so that I could point you its way.

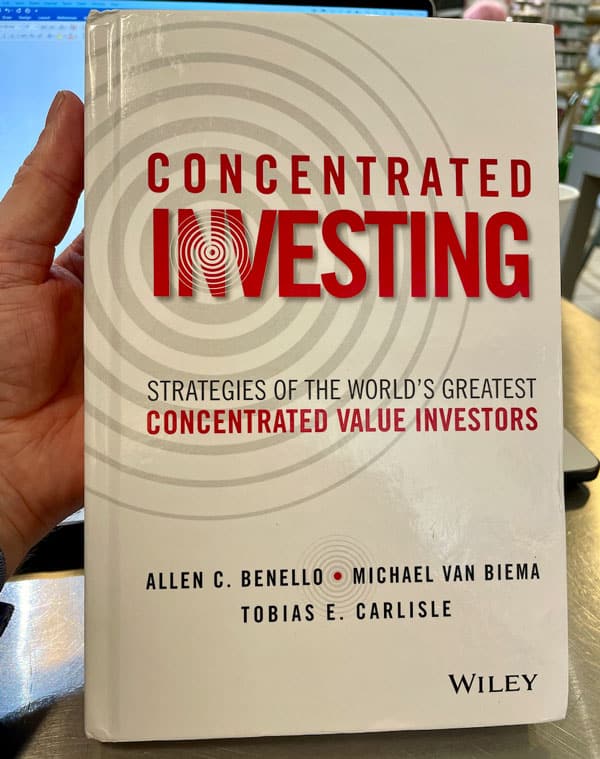

It turned out there is one book that contains everything about the subject that you need to know: "Concentrated Investing: Strategies of the World's Greatest Concentrated Value Investors", published in 2016.

Today's Weekly Dispatch will look at three key questions:

- Who can you learn and take inspiration from?

- How to go about concentrated investing in practical terms?

- Is it really the right strategy for you?

Let's dive right in.

Four role models to learn from

Needless to say, the world's #1 best-known investor who has made concentrated bets is Warren Buffett. However, it's worth recapping just how concentrated some of the bets were that got him off to a good start during the earlier phase of his career.

In 1964, Buffett invested no less than 40% (!) of his investment partnership's portfolio in a single stock – American Express (ISIN US0258161092). The story behind the investment is legendary. Amex had gotten burned by the scandal surrounding the Allied Crude Vegetable Oil company, which was the Enron of its days. Amex took a major financial hit from the scandal and its stock tanked, but the question was, how were customers with American Express credit cards going to react? Staking out restaurants, hotels and banks, Buffett and his partners found out that customers continued to use Amex cards just as before. He saw an opportunity to strike big, and went all in at a time when Amex stock was down and out. The investment quintupled and Buffett's investment partnership made a huge leap forward.

In the history of Buffett's investing, he never invested a higher percentage than in the case of Amex. However, taking concentrated bets was not unusual for him. Five years earlier, Buffett had invested 35% of his partnership's assets in Sanborn Map, a business that was shrinking but which sat on a valuable investment portfolio. As Buffett once explained to students: "If you are a professional and have confidence, then I would advocate lots of concentration."

His sidekick, Charlie Munger, took the concept of concentrated bets even further. Munger defined a very concentrated portfolio as "no more than three stocks". His approach made his portfolio a lot more volatile, but Munger was willing to accept the valleys because he knew the peaks were even greater.

Someone you are less likely to have heard of before is Joe Rosenfield. In 1968, Rosenfield took charge of managing the endowment of Grinnell College in Iowa, when it stood at a paltry USD 11m. By the time he stepped down in 1999, the endowment had grown to over USD 1bn, even though it had to pay 4.75% of its assets to the college every year while he was managing it.

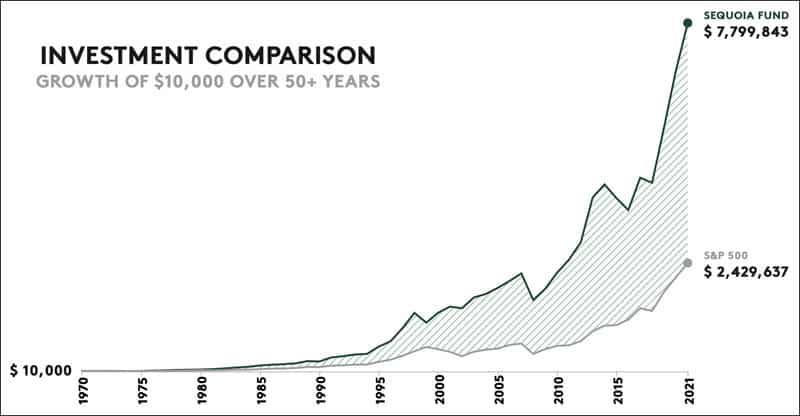

Rosenfield's key to success? Concentrated bets AND holding them (almost) forever. In three decades, he bought not even half a dozen major investments and kept most of them for perpetuity. Unusually for a conservative endowment fund, in 1977, Rosenfield made an investment in an unknown fund: no less than one-third of the endowment went into a relatively young fund managed by a largely unknown fund manager – the Sequoia Fund managed by Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb in New York. At the time, endowments would have been more likely to invest in US treasuries than tying their fate to an emerging fund manager. Rosenfield's assessment proved spot on and the Sequoia Fund became one of the most successful equity funds in US history. Had you invested USD 10,000 in the Sequoia Fund in 1970, you'd now be sitting on USD 7.8m. The college's investment in the fund at one time became one of the largest individual investments in an American mutual fund.

Another highly successful investor you are unlikely to have come across before is Kristian Siem, often dubbed the "Warren Buffett of Norway". Very much in line with his country's strong presence in oil and shipping, Siem focussed on making concentrated bets on undervalued oil and shipping assets. Between 1987 and 2014, he increased his net worth from USD 5m to around USD 2bn, which is equivalent to a compound annual return of 30%. Siem made big bets AND he only ever focussed on assets in oil and shipping. At the peak of his career, he controlled one of the world's largest cruise ship companies.

There'd be plenty of other names to add to this list of examples. The message is loud and clear, though: if you want to make it big in investing, highly concentrated bets certainly are *one* possible way.

What does it take in practical terms, though? Is any of the approaches described above better than the others?

The ONE book you should read about concentrated investing (and yours truly having coffee in Notting Hill).

More than one potential path to pursue

The bad news first: there is no ready-made formula.

The good news: this leaves room for you to carve out your own niche, based on your needs and making use of the opportunities available to your generation of investors.

Usually, as soon as one particular approach in investing has become a huge success, the opportunity is gone. Every generation gets a few big opportunities thrown its way, but no one knows in advance what they will be. If you have an idea of what the next big thing could be and tell your friends about it, they are likely to laugh about it.

That'd actually be a good sign. As I once wrote in a Weekly Dispatch: "Don't invest in it if they don't call you crazy!". The article refers back to my idea of investing in vegan food-related companies in 2017. How well-timed an idea that has turned out, and how much ridicule I faced back in those days!

Druckenmiller and Soros developed an acute sense for trends in the currency markets, and their concentrated bet against the pound sterling literally broke the Bank of England. Their raid on the pound is now part of investment lore, but no one would have thought it possible had you told them in advance. In hindsight, everything looks a lot more obvious and easier.

Buffett made heaps of money by buying Coca-Cola (ISIN US1912161007) and riding a long-term consumer trend. However, will sugary drinks remain a growth market now that half the planet is overweight and diabetes-ridden? Probably not. That ship has sailed, too.

However, nothing should stop you from emulating a few of the methods applied by the star investors mentioned above. For example:

- Find an industry that you are extremely familiar with and make your concentrated bets solely in this sector (Kristian Siem).

- Do the opposite of what the previous point mentions, and instead focus on finding undervalued cash flow in any industry. Develop a deep understanding of accounts and business processes to identify which unfavoured sector currently offers you the chance to buy a future dollar of income for a fraction of its value (Warren Buffett).

- Bet on an emerging fund manager instead of going with an established one. Emerging fund managers offer you a much higher statistical chance of earning outsized return, not the least because smaller funds are generally more agile (Joe Rosenfield).

- Dig through small, unknown stocks. Everything else has already been grazed over by bigger investors. It's in exotic niches that you find hidden gems (Charlie Munger).

Many roads lead to Rome, but you need to pick one and get walking.

Does that sound like a realistic goal for you to pursue? You'll have to honestly answer this question for yourself, but the chaps mentioned above can help you derive at a conclusion.

Could this work for you?

Further up, I only gave you half of Buffett's quote from his talk with students. The complete version reads:

"If you are a professional and have confidence, then I would advocate lots of concentration. For everyone else, if it's not your game, participate in total diversification."

Charlie Munger has a fairly stark way of dividing investors into two categories: professional investors who have what it takes to get an edge in the market, and the "know-nothing investors".

Indeed, making concentrated bets is not for everyone. Much as concentrated bets become fashionable during good times, most people abandon the strategy again during bad times. Concentrated bets magnify market volatility, which can wipe out investors.

However, it's a strategy that is much more open and accessible than you may expect. E.g., you could excel at this strategy even if you have not yet reached world-class analytical skills for understanding companies. Does that surprise you?

Another author looked into this question. Tobias Carlisle, the author behind "Quantitative Value" and "Deep Value" analysed whether success was down to finding the right *companies*, or holding them in the right *amounts*. Surprisingly, world-class skills in analysing companies may even stand in the way of success as you can be so stuck in forever weighing the pros and cons of an investment that the big opportunities sail right past you. Someone else may not have the same analytical skills, but the ability to recognise that sometimes in life, you just have to go for it!

Just to illustrate this point from my own personal experience: in the early 2000s, a foreign brewery conglomerate made a bid approach to a publicly-listed regional German brewery. While the bid terms were a bit unclear, one of the executives of the target company was quoted with a few likely numbers in a local newspaper. If you believed these figures, there was a huge amount of money to be made by loading up on the stock. But could this executive really have spilled the beans in a local newspaper, and could markets be so inefficient that an article in a local newspaper had not yet made it to everyone else's awareness? Proponents of the efficient market theory would have told you this was never going to work. Everyone would have advised you to assume this was a case of "when it sounds too good to be true, it must be too good to be true". I concluded this was one of those instances of life throwing you an opportunity with an outstandingly good risk/reward ratio, bought as much stock as I could afford, and made a serious bundle of money quickly.

This is what Buffett calls "temperament". As he described in 2011:

"The good news I can tell you is that to be a great investor you don't have to have a terrific IQ. If you've got a 160 IQ, sell 30 points to somebody else because you won't need it in investing. What you do need is the right temperament. You need to be able to detach yourself from the views of others or the opinion of others.

You need to be able to look at the facts about a business, about an industry, and evaluate a business unaffected by what other people think. That is very difficult for most people."

As a private investor who manages his own money, I was able to defy conventional wisdom and grab the bull by its horn. Actually, there are several areas where private investors have a real edge.

Why private investors have a few real advantages

As a private investor, it's much easier for you to abstain from group think (at least, as far as your investments are concerned).

If you invest your own money, there is no corporate policy forcing you to subscribe to the latest investment craze. No boss disagreeing with your view, no investment guidelines influencing your decisions, and no compliance department slowing down your decisions.

You also have the advantage that your savings will (likely) be permanent capital. Why is that relevant and why does it put you ahead? If you are seeking outsized returns, you will have to put up with outsized volatility. If you invest permanent capital, sitting through a period of volatility won't have to bother you. As an employed fund manager, you are likely to get fired for outsized volatility – unless your investors have given you permanent capital, as in the case of Berkshire Hathaway's shareholders. Being able to invest permanent capital is a HUGE advantage, and as a private investor investing their own money you naturally have that advantage on your side.

You are also usually much more agile. If you have a few hundred thousand or even a few million to invest, you can access relatively small, obscure, illiquid stocks (and other thinly traded securities, commodities, or alternative assets). The biggest gains are usually made in relatively obscure areas, and if you oversee a portfolio of a few billion, these opportunities will simply not be accessible to you.

Obviously, for all of these points, there will be exceptions and limitations. E.g., there are actually some investment funds that make their clients commit capital for lengthier periods to deal with the issue of volatility. Also, I concede not everyone will be in a position to stash away their investments for the long haul.

Everyone's circumstances are different. This Weekly Dispatch aims to give you a sense for the key aspects of this issue and where you might have an edge. There might not be one for yourself, in which case you should honestly conclude that your needs and possibilities are simply different – at least for now.

Also, circumstances can change over time, just as your investment style can change over time. Rosenfield started as a speculator and became one of the ultimate long-term investors. Buffett famously missed out on the tech stock boom of the late 1990s, only to become one of the largest (and most successful) investors in Apple (ISIN US0378331005) in recent years.

The world is in constant flux and you'll have to adapt your investing to changing times and personal circumstances.

Without a doubt, though, you've got some extraordinary opportunities. I mentioned one such opportunity at the beginning of this article, and it actually makes for a specific investment idea.

Check out Twitter – or regret later

Edwin Dorsey isn't just the current go-to genius for spotting securities fraud, he is also an extremely successful content creator and entrepreneur. With little more than a keyboard and his intellect, Dorsey has created a small publishing operation that is earning him oodles of subscription income.

One of the keys to his success? Dorsey is really good at using Twitter for building an audience for himself.

He "gets" Twitter, and as a result, he has deep insights into the likely future of the platform.

In this regard, he is similar to Kristian Siem. Dorsey has made a huge bet in an industry that he is extremely familiar with, because he spends most of his time in the ecosystem of content creators that has sprung up around Twitter.

What's more, Twitter is a value investment, and one with outsized potential - as concluded in my November 2020 research report "Twitter: Humanity's brain". Twitter stock was USD 43 back then, and it's USD 65 now. I also believe it has a lot further to run, and it might multiply over the coming years.

What makes Twitter the ONE social media stock to own? If you don't know the answer, I urge you to check back to my report.

Just don't put 50% of your net worth into that one stock! (Unless you are a content creator with deep knowledge of the company, that is).

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

A groundfloor opportunity in gaming and esports

Introducing: the European entertainment champion which is looking to turn itself into a global giant - and could gain 125% by mid-2022.

Get in on this opportunity before everybody else becomes aware of it.

My latest research report has all the details. Exclusively available to Undervalued-Shares.com Lifetime Members.